Wilkie Collins, No Name and the Opportunity of China in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

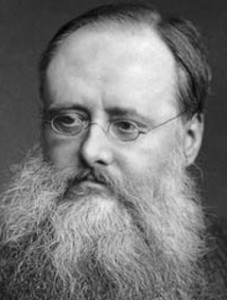

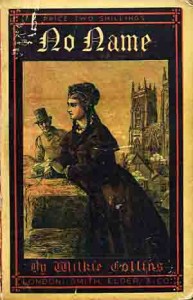

Posted: November 30th, 2013 | No Comments »Andrew Lycett’s new biography of Wilkie Collins, A Life of Sensation is now out. Wilkie Collins and China? Any connections? Appears there is a small one (so perfect for this blog). Collins’s No Name was published in 1862 after he had found success with The Woman in White. It handles the subject of illegitimacy, a serious subject in the mid-nineteenth century of course. The reviewers didn’t like it (a bit scandalous for the times), the public loved it. The plot concerns a young girl, Magdalen Vanstone, who becomes engaged to a rather feckless young man, Francis Clare. Clare is sent off to China to make his fortune.

No Name is actually quite instructive of attitudes to working in China in the 1840s (the book is set 15 or 20 years prior to its publication). Clare works for a firm of traders in the City of London and is to be sent to their “correspondents” in China to familiarize himself with both the tea and silk trades for five years. He is based in Shanghai and arrives in 1846/47. He will return, it is expected, to a position of some rank thanks to his China knowledge and experience. The job is seen as a “banishment” by some of his family but as a means of making good money and eventually establishing his own trading company at some future point by others. It is suggested that while in China opportunities will afford themselves for him to make his fortune. As he is engaged the marriage will have to wait though it is suggested that in one year in the East he will make enough to pay for the dowry and be able to afford to marry.

Also interesting is the role of China in the book in terms of objects. Others who have been to China have returned with objects – Collins describes one house as containing, “Stuffed birds from Africa, porcelain monsters from China, silver ornaments and utensils from India and Peru, mosaic work from Italy and bronzes from France…” Another character heading to China promises to bring back a China shawl and a chest of tea.

Collins’s No Name is not essentially a book about China – China exists as a place far away to which a man may, or may not, go to make, or not make, a fortune but it is a neat literary example of how China was often central to many British families experiences in the mid-nineteenth century and an essential part of Britain’s international trade.

Leave a Reply