Tin Tin, the Secret of Literature, The Blue Lotus and Hergé’s Shanghai Contradictions

Posted: March 17th, 2013 | 1 Comment »I don’t really remember it – I must have been about six or seven – but probably one of my earliest exposures to Shanghai, the International Settlement and China was the Hergé Tin Tin adventure The Blue Lotus. I vaguely remember it being my favourite of all of them (and all of them were devoured both in book form and Saturday morning TV “Hergé’s Adventures of Tin Tin” blaring out at about 9am

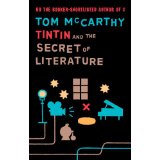

I’ve just read Tom McCarthy’s Tin Tin and the Secret of Literature. There’s an awful lot in this book – a large amount of it totally over my head – you need a pretty in-depth knowledge of the Tin Tin books (which I once did, but it’s slipped in the 30 years since I read them all attentively) and a fondness for French critical theory (which I have never managed to develop, fortunately). Still there is a lot of interesting stuff and, given the focus of this blog, a small discussion of Le Lotus Bleu (1936) seems called for. I’ve made some comments on Hergé, his relationship with his Chinese friend in the 1930s Tchang Tchong Jen and The Blue Lotus before when discussing the work of Shanghailander artists and cartoonists such as Sapajou and Schiff. But perhaps another mention….

These days (I think it’s still true) Hergé is still viewed largely as a man of the right and an acceptor, if not an outright collaborator, with the Nazi occupation regime in his native Belgium. Certainly he was no resistant. However, The Blue Lotus, I think, shows that (like all of us) Hergé was multi-sided and a bit more complicated that the Manichean way he is usually portrayed now. In The Blue Lotus Hergé (through Tin Tin) does take some interesting positions – the book is generally anti-Japanese militarism and interference in China; it is disapproving of the Japanese annexation and occupation of Manchuria (which occurred a year or two before Hergé began work on the story) ; it’s also critical of the condescending and imperialist positions of some foreigners in Shanghai – for instance, the Chief of Police is corrupt, while Tin Tin intervenes to stop a European from mistreating a Chinese rickshaw puller. Overall somewhat contradictory to many of Hergé’s earlier works and later life.

In 1933 Hergé announced that his next Tin Tin adventure would be set in the Far East. Abbe Gossett of the Catholic University of Louvain, a man who looked after several Chinese students studying at the college, wrote to Hergé urging him not to get China wrong or be too stereotyping (bear in mind when you read and look at The Blue Lotus that this was in the early 1930s in Belgium!). Gossett also introduced Hergé to one of the students, Tchang Tchong Jen, from Shanghai. Tchang and Hergé hit it off immediately and became firm friends – art historians can identify the strong influence of Tchang’s Chinese brush and calligraphy styles on Hergé’s work from The Blue Lotus onwards; the book is clearly Hergé’s most richly visual Tin Tin adventure (I’d argue).

There is also a sympathy for Shanghai in the book – Hergé’s vision of Shanghai (a city he never visited) was largely filtered through his friend Tchang and Hergé stated that he was keen not to get Shanghai wrong, while still telling a good story. Of course there is a lot of fun to be had – lots of moon doors on courtyards that are a bit more Peking than Shanghai, Chinoiserie all over the place etc. Still, the book was successful, it did raise awareness of Shanghai and the Japanese threat to the city – a year after its publication of course the Japanese would attack Shanghai and, in December 1941, occupy the International Settlement too. Hergé scholars maintain that, after The Blue Lotus, his work was more detailed and better researched.

During the chaos of the Second World War, and the occupation of Belgium, Hergé and Tchang lost touch. Eventually, much later, when Hergé was a massive cultural star and Tin Tin a worldwide phenomenon, he did find his old Chinese friend. Tchang has returned to Shanghai and later had suffered badly in the Cultural Revolution. Tchang was allowed out to visit Brussels. It was a tricky meeting – the press swarmed the men, Hergé was sick with cancer and Tchang seemed disoriented after decades in Maoist China. Better to remember the men in happier times, before the war, in Brussels, working on The Blue Lotus…

Thank you! A fascinating post.