Auden on the War in China, January 1939

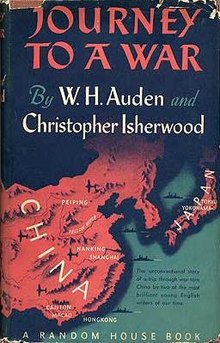

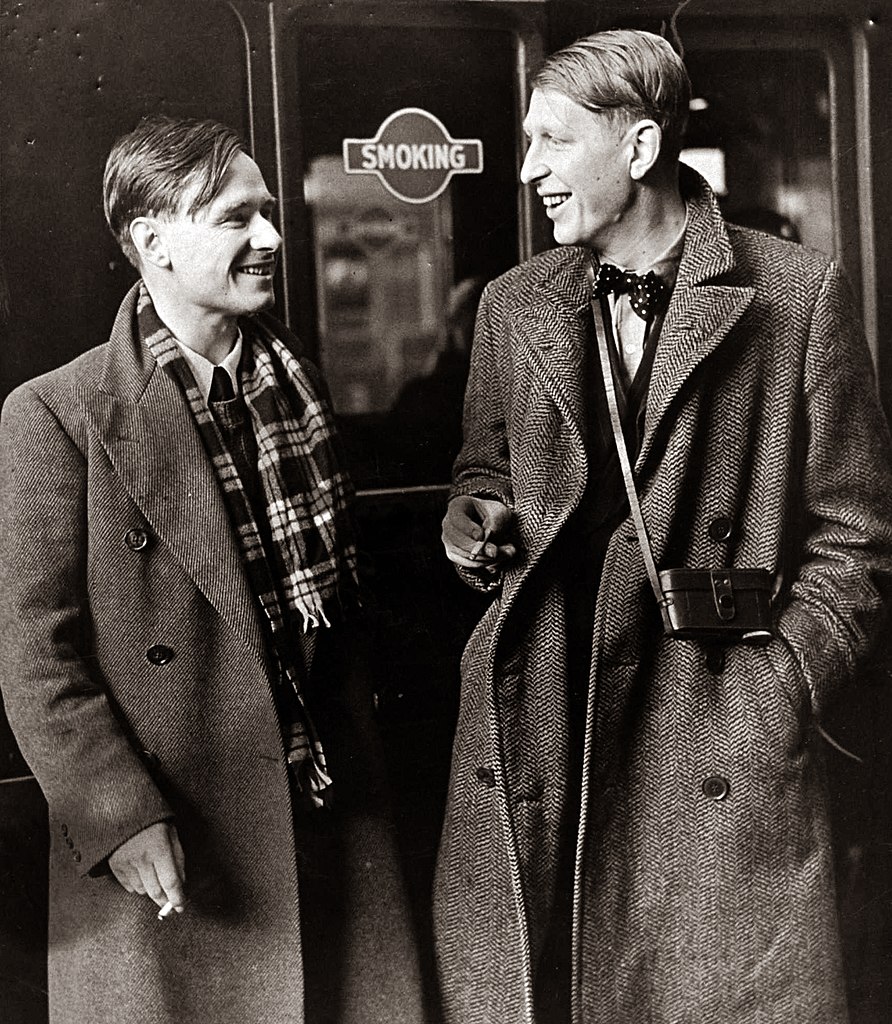

Posted: February 25th, 2022 | No Comments »WH Auden and Christopher Isherwood travelled to Hong Kong, Macao and China in the spring and summer of 1938 to write a travelogue of the war in China commissioned by Faber & Faber. It was a fast writitng job – Isherwood did the text and Auden the accompanying sonnets. Journey to a War was published in Britain in March 1939 with 301 pages for 12s 6d net. In April The Observer noted it as a best selling book alongside Hitler’s Mein Kampf, TS Eliot’s Family Reunion, Isherwood’s own Goodbye to Berlin (later adapted as Cabaret), and Somerset Maugham’s criminally underrated Christmas Holiday. The book was then issued in American by Random House for $3 in August 1939. Readers of this blog, I hope, are familiar with the book….

However, the point of this post is to offer a little something new. As part of the marketing of the book Auden was asked by the BBC to record some impressions of his China trip. The audio archive does exist in the BBC archives. I can tell you that it has a few sound effects – train noises etc – and Auden is rather plummy by today’s standards, as you might expect. Here is the print version to read – Auden on China broadcast on 16th January 1939.

January 16, 1939

I and a friend went to China because we wanted to know what it was like during the war. We stopped first at Hankow. Then we went up the Yellow River. There were two war floods that time, one along the Yellow River and one south of Shanghai. We visited them both by train, car, walking, and once by rickshaw. The authorities gave us every facility to travel and wherever we went soldiers and civilians both seemed genuinely glad to see English people and even grateful. For example, a soldier leaned out of a troop train, laid two fingers side by side and shouted, “England and China together”. We arrived late one night in the pouring rain at a ruined village, which the inhabitants were expecting to evacuate at any moment. So Japs were advancing. And there we found a number of them been standing out in the rain for some time, holding up a banner with the word “WELCOME” in English, written upon it.

Train traveling in China in wartime is more comfortable than you would think. There’s always a tea pot in the compartment, which is never allowed to be empty. And if the train does sometimes stop for days at a time, a market springs up round it at once where you can buy chickens, eggs, peanuts, and so on. Talking of food. A Chinese dinner table looks as if it was set not for eating, but for a lesson in watercolour painting. With this little dishes of coloured sauces, the chopsticks like brushes, even paint rags to wipe the chopsticks off. Many of the dishes such as Bird’s Nest Soup and ancient eggs, we found delicious, but we drew the line at black beetles. Our final impression was that in China, nothing was specifically eatable or uneatable. You could begin munching a hat or biting a mouthful out of a wall. Equally, you could build a hut with the food provided at supper. We had a good many air raids, particularly in Hankow. At night we would go up onto the roof to watch the search light beams plotting the skylight dividers to suddenly they intersected and the Jap planes would be isolated in light, like the bacilli of some fatal disease.

There’s one big air bash in April just after lunch. We put on our sunglasses, lay on our backs on the lawn of the British Consulate. A shell burst near a Japanese bomber flared against the blue like a struck match. Down in the road the rickshaw coolies were delightedly clapping their hands. Then came the whining roar of another machine hopelessly out of control. And suddenly a white parachute mushroomed out over the river. Probably a Chinese plane this time, the Japs, it is said, are not allowed parachutes. A leaflet fluttered down onto the roof of the Consulate to assure the Chinese that Japan was their truest friend.

There is little trench fighting in this war and the actual front is often impossible to find. No one seems to know exactly. The next village is in the hands of the Chinese or the Japanese. The Chinese soldier wears a padded blue uniform rather like an eiderdown quilt. He generally has a couple of hand grenades stuck into his belt like chianti bottles on his back, and either a paper umbrella, or a sword like a gigantic fish knife. The Army Medical Service is pretty primitive. Most of the serious surgical work at the time of our visit was being done by the Mission Hospital.

What is the Chinese war like? Well, least I know it isn’t like wars in history books. You know, those lucid, tidy maps of battles one used to study at school. The flanks like neat little cubes, the pincer movements working with mathematical precision, the reinforcements never failing to arrive. It isn’t like that at all. War is bombing an already disused arsenal, missing it and killing a few old women. War is lying in a stable with a gangrenous leg. War is drinking hot water in a barn and worrying about one’s wife. War is a handful of lost and terrified men in the mountains, shooting at something moving in the undergrowth. War is waiting for days with nothing to do, shouting down a dead telephone, going without sleep, or sex, or a wash. War is untidy, inefficient, obscure, and largely a matter of chance.

Leave a Reply