Posted: December 27th, 2011 | 2 Comments »

This year saw the release of Earnshaw Books’ edited version of Edmund Backhouse’s Decadence Mandchoue in both an English and Chinese version, all edited by Derek Sandhaus. A fascinating book. And, as many of you will know, the old Hermit of Peking was royally trashed by that old fuddy duddy Hugh Trevor-Roper in his bitter and rather nasty biography of Backhouse. Well, Adam Sisman’s biography of Trevor-Roper (or Baron Dacre of Glanton) has just been published in the USA (it’s been out in the UK for a few months already) and, while I wouldn’t read a whole book on Trevor-Roper personally, it is apparently contentious to anyone not inclined to dislike the man.

This year saw the release of Earnshaw Books’ edited version of Edmund Backhouse’s Decadence Mandchoue in both an English and Chinese version, all edited by Derek Sandhaus. A fascinating book. And, as many of you will know, the old Hermit of Peking was royally trashed by that old fuddy duddy Hugh Trevor-Roper in his bitter and rather nasty biography of Backhouse. Well, Adam Sisman’s biography of Trevor-Roper (or Baron Dacre of Glanton) has just been published in the USA (it’s been out in the UK for a few months already) and, while I wouldn’t read a whole book on Trevor-Roper personally, it is apparently contentious to anyone not inclined to dislike the man.

According to the Ephraim Castle column in the Daily Mail last week Sisman quotes Trevor-Roper’s his Oxford Colleague (and China-born son of a Imperial Maritime Customs official) Maurice Bowra as ‘a robot, without human experience, with no girls, no real friends, no capacity for intimacy and no desire to like or be liked.’ Sisman believes that despite being married Trevor-Roper, who was spiteful towards Backhouse for his references to homosexuality, was probably gay himself. Much more in the bio apparently but also suggests that those of us who feel that Backhouse deserves a new and better, more balanced biography have always been right!

Posted: December 27th, 2011 | No Comments »

For years Wen Jiabao has had nothing to say about urban development, architectural preservation or heritage – too busy locking upo dissidents I suppose – and then just as he’s about to enter that good night with the political changes in China next year he suddenly pipes up apparently accusing land developers of destroying traditional heritage and leaving the nation with a culture of “phony” modernisation – no shit Sherlock!

Of course when you dig deeper what really worries Wen is that people pissed off about land seizures, corrupt developers and rapacious officials will rebel rather than any notion of preserving China’s heritage. However, he does point out the stupidity of the ‘knock it down, rebuild it looking old’ tactic which is common and has left the country littered with crappy reconstructions of buildings now lost forever.

So much so good – ultimately Wen doesn’t really have much to say of any substance as usual – even Xinhua seems to be skeptical if I’m intepreting their final line of the article rightly – “Wen has repeatedly vowed to do more for ordinary people, including ridding his government of corruption and ushering in political reforms.” He has indeed and sadly failed totally to achieve these objectives. Shouting about it at 5 minutes to midnight in his political career is a tad pointless.

The whole article here

Posted: December 26th, 2011 | 1 Comment »

What could be more Christmas than Dickens? Not much to me – it’s a time to watch A Christmas Carol, remember Tiny Tim and lap up all that Victorian London seasonal feel stuff. This year Dickens fans have had a special treat – like many others I’ve spent Christmas reading Claire Tomalin’s excellent Charles Dickens A Life which, among other things mostly London-centred, got me thinking about Dickens and China. So here’s my guide to Dickens and his China references, including those that are a bit of a stretch – I’ve remembered as many as I can but if anybody has any others do let me know.

- Dickens knew that the mere hint of a past in the East was enough to pique the readers interest – in Little Dorrit (first published in serial form in 1855) Dickens’s Arthur Clennam raises the reader’s interest when he is shown returning to London after working for fifteen years in China with his recently deceased father. As his father died, he has given Arthur a mysterious watch, murmuring, “Your mother.†Naturally Arthur assumes it is intended for Mrs. Clennam, whom he and the world supposed to be his mother. Inside the watch casing is an old silk paper with the initials D N F (Do Not Forget). It is a message – but when Arthur shows it to the harsh and implacable Mrs. Clennam, a religious fanatic, she refuses to reveal what it means. So begins one of Dickens’s best loved books of twists and turns of fortune and misfortune which though written in the mid-nineteenth century is actually set in the 1820s.

- Dickens notes the popularity of tea from China among the working classes and wrote the rhyme in Barnaby Rudge (1841))  ‘Polly put the kettle on, we’ll all have tea’, which was still being sung by my nan in the 1970s!

- Dickens noted opium several times and in Bleak House (1852) the destitute Captain Hawdon dies of an opium overdose. Dickens had visited a Shadwell opium den in East London conducting research for what would become his last, and unfinished, novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). In the opening scene, Dickens’s character John Jasper, who lives a double life as an opium addict and a respected member of society, awakens from a narcotic slumber in an opium den with two other semi-conscious men and their supplier, an old woman named Princess Puffer, based on a real life elderly East End pusher Dickens had met theatrically known as “Opium Salâ€:‘At the bottom of this slough of grimy Despond is the little breathless garret where Johnny the Chinaman swelters night and day curled up on his gruesome couch, carefully toasting in the dim flame of a smoky lamp the tiny lumps of delight which shall transport the opium-smoker for a while into his paradise.’ Dickens apparently didn’t think much of the East End or the Chinese but perhaps saw that opium could be better than alcohol abuse. Opium Sal explains as she prepares a pipe: ‘O me, O me, my lungs is weak, my lungs is bad! It’s nearly ready for ye, deary. Ah, poor me, poor me, my poor hand shakes like to drop off! I see ye coming-to, and I ses to my poor self, “I’ll have another ready for him, and he’ll bear in mind the market price of opium, and pay accordingly.†O my poor head! I makes my pipes of old penny ink-bottles, ye see, deary – this is one – and I fits-in a mouthpiece, this way and I takes my mixter out of this thimble with this little horn spoon; and so I fills, deary. Ah, my poor nerves! I got Heavens-hard drunk for sixteen years afore I took to this; but this don’t hurt me, not to speak of. And it takes away the hunger as well as wittles, deary.’

- Opium eaters were often differentiated from opium smokers as the former became hooked after using opium for medicinal purposes and the latter while using the drug recreationally. They were a commonly acknowledged social group – Dickens has Mr Pickwick refers to the rather dim-witted servant Joe, the “fat boyâ€, as a ‘young opium eater’ in The Pickwick Papers (1836).

- And finally, of course Dickens never went to China but he did set foot aboard a Chinese junk (below), one that had actually been sailed from Hong Kong, moored at Blackfriars Bridge from 1848 attracting crowds of curious visitors. Dickens went twice. I posted more details on the Blakfriars junk back in 2008 here.

Posted: December 25th, 2011 | No Comments »

It’s become a sort of China Rhyming tradition (and I do like tradition) to offer up to you dear reader a longer tale on Christmas Day – see here for last year’s tale of a warlord converted – and this year I thought I’d dig out that old swashbuckler and all round swordsman (as they used to say of men who were able with the ladies) Errol Flynn and his Shanghai sojourn. So here from his 1959 autobiography My Wicked, Wicked Ways is Flynn’s own account of his Shanghai:

We lined up at the end of Hu Tung Avenue, where the recruiting barracks were. Inside the low-slung structure, a clammy horrible-looking fortress, there were hundreds of us. Some had beards, some were clean-shaven, but apparently they were just as much out of a job as we were.

A young, fair-haired English subaltern with a blond moustache, five hairs on the left side of his upper lip, about seven on the right, with a notebook in his hand, followed by a corporal, was trying to get some order. An officer stepped forward and told us what our duties would be. We would go to Shanghai, already under fire, and barricade it before the Japanese had a chance to move in any further.

We were now soldiers.

We were issued a rifle apiece. Ammunition would be given to us in Shanghai, because the available bullets didn’t fit the available rifles. It would probably be cold in Shanghai, so we were issued greatcoats.

We were marched to the wharf. There we took ship for Shanghai, about four hundred of us, on a small China coaster.

I was a British subject, Koets was an American, and by joining up he had lost his citizenship, although this never occurred to him at the time. Americans who enlist in foreign wars are frowned on. Through all this passage he managed to hang on to his magic steel box containing all his paraphernalia, personal belongings and photographic equipment – and even some snake juice.

Three days later we disembarked. We could hear gunfire. Shanghai was already under siege. It was being attacked on the far bank. Boats anchored in the harbour were under fire.

“This is it, Koets! We’re in it!†Now for the loot, the jade, the daughters of the Mings, the treasures of ancient Cathay!

On the wharf we were greeted by another little Englishman dressed in a fancy uniform. He said we would immediately be put in the front line against the Japanese.

While we listened, what really engaged our attention was the heavy snowfall all around. The snow was two or three feet deep. I hadn’t seen snow in a long time, not since Tasmania. I stood there shivering, wearing that too-small army coat and glad I had it.

“Now,†said the little officer, “hand over your guns.â€

The guns were taken away from us. What the hell was this!

Suddenly a squad of Chinese came on to the scene carrying big heavy shovels and they were going down the ranks handing each of us a shovel!

“Shitz!†growled Koets, lapsing into dialect, “Vat kind of a war is dis!â€

The commanding officer barked, “You will proceed to the outskirts of the city and there entrench!â€

Koets and I asked what this was for. We were told, “Shut up and just do the job. You are Hong Kong Volunteers.â€

The next three weeks we dug and dug. First we had to dig away the snow. Then we had to turn up the earth and pile up embankments behind which Shanghai would defend itself. Barbed wire went up. Trenches took form.

The food was not for description. The sleeping accommodation was meant for Chinese beetles.

Treasures of Cathay! I was doing more fast thinking than I had done since I put one over on the Lului chieftain back in New Guinea.

While we dug, occasional bullets were flying over our heads. Some fell short of where we were digging.

For days Koets and I gave each other odd looks, expressive of ideas, schemes, designs.

Finally our feelings burst from us simultaneously.

“Look at your hands,†I said, feeding him a small touch of sedition. “Full of blisters! Those hands of yours were meant for operating with.â€

“You are absolutely right, you idiot, absolutely!â€

“Why don’t we beat it?â€

“Desert?â€

“Watch your vocabulary, “ I whispered.

“That’s what it is – but I’m for it. I’ve had enough!â€

For the next few days Koets did the primary scouting. He found a couple of Chinese boys who agreed to take us to a spot on the waterfront nearby where we could get a packet headed down the coast. If we had the money, our passports and a Shanghai Province Permit to get out with, we had a deal.

What the hell was a Shanghai Province Permit?

Koets, whispering to me between shovelfuls of earth, explained that the Shanghai Province Permit might present the greatest problem. It was a small card, rudely comparable to a visa, which said foreigners could not over-extend their stay in the Shanghai Province without official sanction, and meaning it was okay to leave before a certain date stamped on it.

We located someone in the Hong Kong Volunteers who had such a permit. I examined it. What I saw gave me hope and an idea.

I looked through my kit of personal effects. Among the papers, receipts were several Chinese laundry slips. Now to get two of these fixed properly…

I worked over one of them. Down in one corner were the words in English: not responsible for laundry left here over six months. Good, that was the spot to cover with a big British sixpence stamp. I affixed a big blub of sealing-wax, with my thumb print on it. Next to that I wrote boldly in thick black ink: OK, ERROL FLYNN. I performed the same operation with Koets’s slip, and he signed his name with the same OK.

I forged some Chinese hieroglyphics to it. Then, for the first time since childhood, I prayed, however irreverently, to God. “Look, Sport,†I said to Him, “Get us out of this Egg Foo Yong.â€

Koets had some medical equipment and we now had enough Shanghai to get on a boat.

One evening when, ostensibly, we adjourned to the latrine, we stole out of the barracks.

We hustled down to the waterfront, where we met a wizened little fellow who said, like I had heard in whorehouses in New Guinea and the Philippines, “The money, please,†with his hand held out.

We were taken on board a bedraggled little packet no more than twenty feet long and perhaps a third of that in the beam. It smelled as if it had been well lived in.

The captain asked to see our credentials, just in case he was stopped en route anywhere and questioned why he was carrying two foreigners. We showed him our papers.

I had carefully stamped this pink laundry slip in a Chinese lettering which meant ‘Good until December 1933’. He fingered that with care, looked at it suspiciously, as Koets shoved some Shanghai at him.

The laundry slip was okay. So were the Shanghai. We could get out of China.

If we were in luck, our arrow was at last pointing west.

I think I might justly claim to be the only man who travelled through China with a laundry slip for a passport.

Posted: December 25th, 2011 | No Comments »

To one and all…

Posted: December 24th, 2011 | No Comments »

As it’s the holidays a somewhat longer post…

Despite the best attempts of modern Shanghai’s leaders to present the city as an aspirant International Financial Centre, regional logistics hub, mega-port and (said with straight faces at government press briefings) centre of ‘knowledge workers’, the older image of Shanghai as a raffish city, an edge city positioned between a notional western civilization and a perceived eastern barbarism, a teeming Oriental city, a criminal city persists. Pearl of the Orient can never quite nudge out Whore of the Orient. Since the early decades of the twentieth century to come from, or to have had some contact with, Shanghai was a mark of disreputability, possible nefarious undertones and a general loucheness. Wallis Simpson never lost the taint of Shanghai, her induction into the mysteries of the “Shanghai Grip†and those long rumoured pornographic photos – references to her shady Shanghai experiences cropped up in the UK Channel 4’s adaptation of William Boyd’s Any Human Heart as well as the new Upstairs Downstairs (now transposed to 1937 and where it was Wallis’s lesser reported Peking sojourn that got the mention). We also got another Wallis Simpson bio this year (as we do at least once every year) with Anna Sebba’s That Woman which did cover the Shanghai years.

And the Shanghai references have just kept on coming of late. Television, British tele at least, seems still to like a Shanghai reference. When Hastings’ Inspector Foyle (Michael Kitchen) of Foyle’s War is called to investigate a murder during the war at an old country house (Episode 9 – The French Drop) he discovers it taken over for training purposes by a band of secret British operatives in Special Operations Executive teaching soldiers hand-to-hand combat and the black arts. They attempts, as secret service types always do when confronted with ordinary honest coppers going about their business, to dissuade Foyle from his investigation. The most ruthless of them is introduced as a former Shanghai Municipal Police officer who, during his time in the East, has learnt the intricacies of knife fighting. This is a clear reference to William E Fairburn, the former SMP officer and world expert in knife fighting and street fighting who developed the Defendu fighting technique Indeed Fairburn did return to Britain during the War and did train British Commandos, as well as American and Canadian soldiers, in unarmed combat, knife fighting and generally how to kill as many Germans as possible rapidly and efficiently. It has been suggested that Ian Fleming came across Fairburn during his time in Naval Intelligence during the war and used him as one possible model for Q in the James Bond books.

And the Shanghai references have just kept on coming of late. Television, British tele at least, seems still to like a Shanghai reference. When Hastings’ Inspector Foyle (Michael Kitchen) of Foyle’s War is called to investigate a murder during the war at an old country house (Episode 9 – The French Drop) he discovers it taken over for training purposes by a band of secret British operatives in Special Operations Executive teaching soldiers hand-to-hand combat and the black arts. They attempts, as secret service types always do when confronted with ordinary honest coppers going about their business, to dissuade Foyle from his investigation. The most ruthless of them is introduced as a former Shanghai Municipal Police officer who, during his time in the East, has learnt the intricacies of knife fighting. This is a clear reference to William E Fairburn, the former SMP officer and world expert in knife fighting and street fighting who developed the Defendu fighting technique Indeed Fairburn did return to Britain during the War and did train British Commandos, as well as American and Canadian soldiers, in unarmed combat, knife fighting and generally how to kill as many Germans as possible rapidly and efficiently. It has been suggested that Ian Fleming came across Fairburn during his time in Naval Intelligence during the war and used him as one possible model for Q in the James Bond books.

Shanghai pops up again, this time as somewhere westerners, and particularly obviously the upright and uptight English risk losing their moral compass. A recent episode of the new Marple (ITV), based on the Agatha Christie Miss Marple books, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? ended with the murderers being two young people raised in China and apparently sold into slavery in Shanghai only to be debauched and to indulge in a range of sins seemingly including incest. The British public watching on a Sunday evening got the reference that Shanghai equals sexual louchness, helped along by the fact that the Shanghai-corrupted murderess, complete with full body dragon tattoo, was played by Natalie Dormer an actress best known to British TV audiences as Anne Boleyn in The Tudors – a show that is responsible for everyone now thinking Anne was scheming, sexy, versatile in bed and an all round hottie (which, to be fair, Dormer is even if Anne wasn’t). A small problem is that Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? was written by Christie in 1934 but was never a Miss Marple book – it’s a serious re-write with a louche Shanghai background replacing what would now appear a rather dated ‘father was a big game hunter’ storyline.

Shanghai pops up again, this time as somewhere westerners, and particularly obviously the upright and uptight English risk losing their moral compass. A recent episode of the new Marple (ITV), based on the Agatha Christie Miss Marple books, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? ended with the murderers being two young people raised in China and apparently sold into slavery in Shanghai only to be debauched and to indulge in a range of sins seemingly including incest. The British public watching on a Sunday evening got the reference that Shanghai equals sexual louchness, helped along by the fact that the Shanghai-corrupted murderess, complete with full body dragon tattoo, was played by Natalie Dormer an actress best known to British TV audiences as Anne Boleyn in The Tudors – a show that is responsible for everyone now thinking Anne was scheming, sexy, versatile in bed and an all round hottie (which, to be fair, Dormer is even if Anne wasn’t). A small problem is that Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? was written by Christie in 1934 but was never a Miss Marple book – it’s a serious re-write with a louche Shanghai background replacing what would now appear a rather dated ‘father was a big game hunter’ storyline.

A simple reference to a Shanghai past works wonders when it come to character development. A current vogue in British crime fiction is for books set in the late 1940s and early 1950s – post-war austerity and pre-swinging 60s cool combine and resonate with a current readership mired in recession and austerity themselves, though with less bombsites around these days admittedly. Elizabeth Wilson’s War Damage (Serpent’s Tail, 2009) takes us to post-war Hampstead where the Bohemian set are getting started again after six years of fighting the Nazis. One suspect immediately shoots up the “most likely to be guilty of something†list when it is mentioned that he had spent many years before the war in Shanghai, in antiques or something. Clearly someone who needs further investigation. Australian writers Mardi Macconnochie and Anna Funder both have post-war flashbacks to pre-war Shanghai in their recent novels, The Voyagers (Penguin, 2011) and (for my money the best novel of 2011) All That I Am (Penguin, 2011) respectively. Mardi opts for the refugee semi-criminal nightlife of pre-war Shanghai while Anna has a small reference to one of her anti-Hitler resisters taking of for Shanghai to escape European fascism. Interesting to note that both have been visitors and participants at the Shanghai International Literary Festival in past years so clearly their between-session strolls around the town have come in useful.

A simple reference to a Shanghai past works wonders when it come to character development. A current vogue in British crime fiction is for books set in the late 1940s and early 1950s – post-war austerity and pre-swinging 60s cool combine and resonate with a current readership mired in recession and austerity themselves, though with less bombsites around these days admittedly. Elizabeth Wilson’s War Damage (Serpent’s Tail, 2009) takes us to post-war Hampstead where the Bohemian set are getting started again after six years of fighting the Nazis. One suspect immediately shoots up the “most likely to be guilty of something†list when it is mentioned that he had spent many years before the war in Shanghai, in antiques or something. Clearly someone who needs further investigation. Australian writers Mardi Macconnochie and Anna Funder both have post-war flashbacks to pre-war Shanghai in their recent novels, The Voyagers (Penguin, 2011) and (for my money the best novel of 2011) All That I Am (Penguin, 2011) respectively. Mardi opts for the refugee semi-criminal nightlife of pre-war Shanghai while Anna has a small reference to one of her anti-Hitler resisters taking of for Shanghai to escape European fascism. Interesting to note that both have been visitors and participants at the Shanghai International Literary Festival in past years so clearly their between-session strolls around the town have come in useful.

One other writer deserves a mention as well – Lisa See, who’s become a veritable font of China books in recent years. Her 2009 bestseller Shanghai Girls (Bloomsbury) was interesting readers got a twist on the usual penniless Chinese peasant finally makes it to America, works hard and realises that the USA really is the Gold Mountain. See’s characters, the sisters Pearl and May, arrive in Los Angeles in 1937 from a Shanghai that leaves LA in the dust in terms of modernity. It is their Californian Chinese husbands who are the doltish bumpkins; LA, or at least its Chinatown, is seen as far behind Shanghai in terms of fashions, trends and just general knowingness. The follow up to Shanghai Girls, Dreams of Joy came out this year.

Shanghai it seems remains a popular symbol.

Posted: December 23rd, 2011 | 1 Comment »

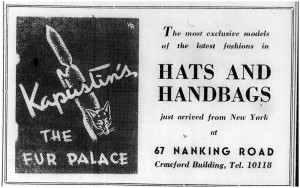

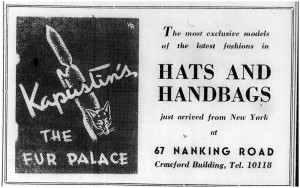

Christmas is almost upon us – late with the shopping? Kapustin’s might have something among there lovely range of hats and handbags, all the latest models and handily just along the Nanking Road. I know some of you might not like fur these days but there’s plenty of other stuff.

Posted: December 23rd, 2011 | No Comments »

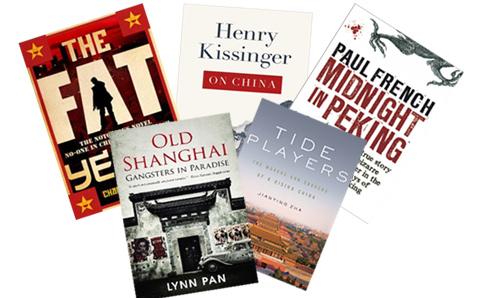

The Time Out Shanghai Best China Books of the Year list is out for 2011. OK, so I like that I’m included and I like the line – “Midnight in Peking has all the page turnability of a Ruth Rendell mystery.” However, The Fat Years was also good as was Lynn Pan’s Gangsters in Paradise and Zha Jianying’s Tide Players. Of course I don’t like that Kissinger, the murdering old war criminal, is on the list but some people seem to find him interesting for some reason (of course, the recently and sadly departed Hitch always knew better than to praise him).

This year saw the release of Earnshaw Books’ edited version of Edmund Backhouse’s Decadence Mandchoue in both an English and Chinese version, all edited by Derek Sandhaus. A fascinating book. And, as many of you will know, the old Hermit of Peking was royally trashed by that old fuddy duddy Hugh Trevor-Roper in his bitter and rather nasty biography of Backhouse. Well, Adam Sisman’s biography of Trevor-Roper (or Baron Dacre of Glanton) has just been published in the USA (it’s been out in the UK for a few months already) and, while I wouldn’t read a whole book on Trevor-Roper personally, it is apparently contentious to anyone not inclined to dislike the man.

This year saw the release of Earnshaw Books’ edited version of Edmund Backhouse’s Decadence Mandchoue in both an English and Chinese version, all edited by Derek Sandhaus. A fascinating book. And, as many of you will know, the old Hermit of Peking was royally trashed by that old fuddy duddy Hugh Trevor-Roper in his bitter and rather nasty biography of Backhouse. Well, Adam Sisman’s biography of Trevor-Roper (or Baron Dacre of Glanton) has just been published in the USA (it’s been out in the UK for a few months already) and, while I wouldn’t read a whole book on Trevor-Roper personally, it is apparently contentious to anyone not inclined to dislike the man.