Posted: January 9th, 2014 | No Comments »

Talking of the collection at the Musee d’Orsay China Rhymers might find Edouard Manet’s portrait of the writer Emile Zola of interest. Zola was a massive and early fan of Manet’s and, as a thank you, Manet painted this portrait of the author in 1868. Manet painted Zola in his study and included many of the artifacts and works of art in that room that meant a lot to the author. These interestingly included a Japanese print of a wrestler by Utagawa Kuniaki and it is featured prominently in the portrait. The Far East, which was revolutionising ideas on perspective and colour in European painting, played a central role in the advent of the new style of painting in Europe. A Japanese screen partially displayed on the left of the picture recalls this. the inkwell on Zola’s desk, obviously indicating his occupation, also appears to be Chinese or Asian of some sort, but might not be. Zola had apparently compared Manet’s style to Japanese woodcuts for his use of similar techniques and both Zola and Manet appreciated the Japanese art that was available for viewing in Paris.

Posted: January 8th, 2014 | No Comments »

Who exactly was The Clowness Cha-U-Kao who featured in Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1895 painting of the same name? Well, it seems Cha-U-Kao was a dancer and performer at Paris’s Nouveau Cirque and then the Moulin Rouge. Her Japanese sounding name originated from a phonetic transcription of the French ChaHut, a combination of the words for a more acrobatic version of the Can-Can and the French for chaos. It was a dance at which she excelled and the crowd went wild when she came on stage. She brought the skills of the circus to the cabaret and Toulouse-Lautrec obviously loved her.

Here’s a rather saucy shot of Cha-U-Kao and a headdress of possibly Indo-Chinoiserie inspiration

Here’s a rather saucy shot of Cha-U-Kao and a headdress of possibly Indo-Chinoiserie inspiration

Posted: January 7th, 2014 | No Comments »

A few posts on various Chinoiserie and other Orientalist bits and bobs gleaned from a recent trip to Paris – well, not that recent actually but I’ve not got around to posting for ages.

First off a trip to the Moulin Rouge to watch the Can-Can. The current show on offer features one particular dance number that is a glorious Orientalist mash up featuring Chinoiserie, Indo-Chinoiserie and some Indian inflections too. A complete mess, but great fun. Of course Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was the great artist of the Moulin Rouge, and the Musee d’Orsay in Paris contains his painting La Danse Mauresque (The Moorish Dance) from 1895 which also appears to be an Orientalist mash up with a be-turbaned Indian alongside a traditional Moulin Rouge chorus line girl. The painting was done as a panel for the house of La Goulue (The Glutton) at the Foire du Trone in Paris. La Goulue (actually Louise Webster) was a Can-Can dancer known as the Queen of Montmartre and a great favourite of Toulouse-Lautrec. The Foire du Trone is an annual festival that takes place in the Forest of Vincennes near Paris featuring various acts.

.

.

La Goulue

Posted: January 6th, 2014 | No Comments »

Last year I published a small e-book of more tales from Midnight in Peking called The Badlands: Decadent Playground of Old Peking. The book was a combination of various stories of characters who inhabited the Peking Badlands in the 1930s I hadn’t had room for in Midnight in Peking plus some information and photographs on various characters that emerged and was told/sent to me after the book came out. It includes a map of the old Badlands and illustrations courtesy of Jason Pym. Hopefully the book adds some more details and life to the long forgotten old district of sin in Peking. Now Penguin Australia has published the book in paper format as a Penguin Special.

Posted: January 5th, 2014 | No Comments »

I never got round to writing up my favourite China books of 2013 (or worst)…too late now. Anyway, here’s a few (of the many) China books (not including anything I’ve written, contributed to, edited or commissioned) forthcoming in the first few months of 2014 that may interest the China Rhyming Community (if indeed such a thing actually exists!) – in no particular order and with publishers blurbs:

China Dolls – Lisa See – The New York Times bestselling author of Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Peony In Love, Shanghai Girls, and Dreams of Joy returns with her highly anticipated new novel. A bold and bittersweet story of secrets and sacrifice, love and betrayal, prejudice and passion, China Dolls reveals a rich portrait of female friendship, as three young women navigate the “Chop Suey Circuitâ€â€”America’s extravagant all-Asian revues of the 1930s and ’40s—and endure the attack on Pearl Harbor and the shadow of World War II.

I am China – Xiaolu Guo – In a flat above a noisy north London market, translator Iona Kirkpatrick starts work on a Chinese letter: Dearest Mu, The sun is piercing, old bastard sky. I am feeling empty and bare. Nothing is in my soul, apart from the image of you. I am writing to you from a place I cannot tell you about yet. In a detention centre in Dover exiled Chinese musician Jian is awaiting an unknown fate. In Beijing his girlfriend Mu sends desperate letters to London to track him down, her last memory of them together a roaring rock concert and Jian the king on stage. Until the state police stormed in. As Iona unravels the story of these Chinese lovers from their first flirtations at Beijing University to Jian’s march in the Jasmine Revolution, Jian and Mu seem to be travelling further and further away from each other while Iona feels more and more alive. Intoxicated by their romance, Iona sets out to bring them back together, but time seems to be running out.

The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream – Dan Washburn – Statistically, zero percent of the Chinese population plays golf, still known as the rich man s game and considered taboo. Yet China is in the midst of a golf boom hundreds of new courses have opened in the past decade, despite it being illegal for anyone to build them. Award-winning journalist Dan Washburn charts China s economic and political fortunes through the lives of three men intimately involved in the country s bizarre golf scene. We meet Zhou, a peasant turned golf pro who discovered the game when he won a job as a security guard on one of the massive construction sites and who sees the game as his key to the emerging Chinese middle class; Wang, a lychee farmer whose land is confiscated for an ecological park and resorts to setting up a food kiosk on a nearby track; and Bill, a Western executive manoeuvring through China s byzantine bureaucracy (as well as Thai gangs), ever watchful for Beijing s golf police . The Forbidden Game is a rich and engrossing portrait of the world s newest superpower and three different paths to the Chinese Dream.

America’s First Adventure in China: Trade, Treaties, Opium, and Salvation – John Rogers Haddad – In 1784, when Americans first voyaged to China, they confronted Chinese authorities who were unaware that the United States even existed. Nevertheless, a long, complicated, and fruitful trade relationship was born after American traders, missionaries, diplomats, and others sailed to China with lofty ambitions: to acquire fabulous wealth, convert China to Christianity, and even command a Chinese army. In America’s First Adventure in China, John Haddad provides a colourful history of the evolving cultural exchange and interactions between these countries. He recounts how American expatriates adopted a pragmatic attitude – as well as an entrepreneurial spirit and improvisational approach – to their dealings with the Chinese. Haddad shows how opium played a potent role in the dreams of Americans who either smuggled it or opposed its importation, and he considers the missionary movement that compelled individuals to accept a hard life in an alien culture. As a result of their efforts, Americans achieved a favourable outcome – they established a unique presence in China – and cultivated a relationship whose complexities continue to grow.

Impressions of a Lost World: A Century of Chinese Photography, 1860-1950 – Ferdinand Bertholet, Lambert Van Der Aalsvoort & Regine Thiriez – The flourishing of photography as a medium in the mid-19th century coincided with a rise in curiosity about China on the part of the Western world. As the number of foreigners living and travelling in China increased, early photographs of China were taken by and for an international audience. Impressions of a Lost World assembles 250 fascinating images of China in the second half of the 19th century and first half of the 20th, captured by the Western camera lens. The photographs portray the gritty side of the country as well as stunning views of palaces, temples, harbours and gardens. This juxtaposition of the sordid and the serene provides a multidimensional picture of China’s physical and social landscape before Mao Zedong’s ascent to power changed the country forever. The photographs, many published here for the first time, are both beautiful and moving, and together offer a new understanding of a social and cultural history associated with a time of significant historical change.

Posted: January 4th, 2014 | No Comments »

Funny how so many of the great crime and espionage writers have taken excursions to Asia in their careers. Of course Graham Greene wrote The Quiet American (1955) about Indo-China and set largely in Saigon while John Le Carre’s The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) is still by far one of the best books about Hong Kong, and one of the only featuring Vientiane. Eric Ambler, the great espionage writer of the 1930s, dipped into Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia in Passage of Arms (1959). In fact that’s a pretty good reading list to kick of 2014 if you haven’t read those books.

One writer who also has a fleeting venture to the region is Nicholas Freeling, the creator of the Commissaris Van der Valk series, of which there are about a dozen novels featuring the Amsterdam-based detective. Tsing-Boum! (1969) is one of the later ones in the series and has the Commissaris travelling to France and Belgium on the trail of a murder which has its origins in the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu (a central event for Greene too obviously) and recriminations that ratchet down the decades….

Posted: January 3rd, 2014 | No Comments »

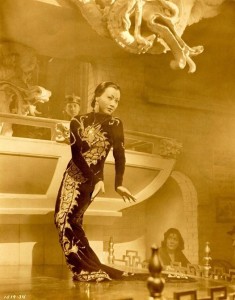

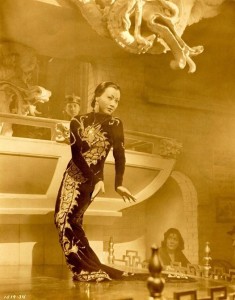

Anna May Wong – born today in 1905….seen here in Limehouse Blues (1934)

Posted: January 2nd, 2014 | 1 Comment »

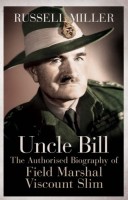

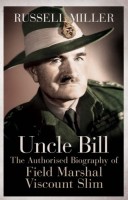

Though the publishers loudly trumpet it – I’d argue that “written with the full co-operation of the Slim family” is a worry rather than an endorsement. There is a problem with biography, or writing about anyone who has ancestors still knocking about (believe me, I should know!) – they tend to see their ancestors differently to the historian, the biographer or the story teller. Consequently they get very defensive and irate if you deviate from their family-agreed script (again, believe me, I should know!). This is why “official biography” is invariably boring and rote compared to the “unofficial” – the “official” biographer always has (either metaphorically or actually) a concerned and censoring descendent looking over their shoulder as they write. A biogapher must be able to research and interpret a person without fear or favour….Yes, you get access to all sorts of things; yes, you avoid treading on any toes and ending up in feuds with unhappy family members (I know, I know) who think anything less than sainthood for their esteemed ancestor is treachery, but you don’t inevitably capture the subject….

That’s the problem with this new biography of Field Marshal Viscount Slim, Uncle Bill – it’s largely a piece of fluffery to big up the man and so ensure co-operation from the family – it’s official, approved and we get all the minor charitable acts and the sort of things families like to boast about but not so much of the man himself with all the messy conundrums Slim, and the rest of us, are all made up of. Still, for those characters that are not being “officially” bio-ed here things get more interesting – Stilwell and his hatred of the Brits, the vainglorious Wingate, the problematic Chinese of course and Chiang Kai-shek’s failure to commit in Burma. Worth a read, but with the same pinch of salt you take tales of your marvellous old Uncle Stan from your loving old Aunt Agatha…

In 2011 the National Army Museum conducted a poll to decide who merited the title of ‘Britain’s Greatest General’. In the end two men shared the honour. One, predictably, was the Duke of Wellington. The other was Bill Slim. Had he been alive, Slim would have been surprised, for he was the most modest of men – a rare quality among generals. Of all the plaudits heaped on him during his life, the one he valued most was the epithet by which he was affectionately known to the troops: ‘Uncle Bill’.

Born in Bristol in 1891, the son of a small-time businessman, he was commissioned as a temporary Second Lieutenant on the outbreak of the First World War. Seriously wounded twice, in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, he was awarded the Military Cross in 1918. Between the wars he served in the Indian Army with the Gurkhas and began writing short stories to supplement his income.

Promotion came rapidly with the Second World War, and in March 1942 he was sent to Burma to take command of the First Burma Corps, then in full flight from the advancing Japanese. Through the force of his leadership, Slim turned disorderly panic into a controlled military withdrawal across the border into India. Two years later, having raised and trained the largest army ever assembled by Britain, Slim returned to drive the enemy out of Burma and shatter the myth of Japanese invincibility which had hamstrung Allied operations in the East for so long. Probably the most respected and loved military leader since the Duke of Marlborough, he later became a popular and successful Governor-General of Australia in 1953, was raised to the peerage, and died in London in 1970.

.

.