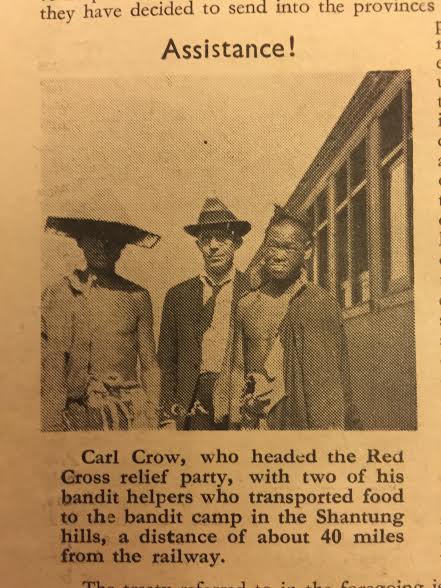

Carl Crow and Bandit Helpers – Lincheng, Shandong, 1923

Posted: January 15th, 2016 | No Comments »My thanks to Doug Clarke – author of the excellent Gunboat Justice trilogy – for this picture of Carl Crow, with two of his bandit helpers, at Lincheng in Shandong in 1923. Bandits had taken foreigners and Chinese hostage from a train; Carl Crow, on behalf of the Red Cross, was sent in to negotiate. It’s a great story and I attach it below as an excerpt from my biography of Crow, A Tough Old China Hand. What a great photo!!

Becoming a Warlord’s Elder Brother

Of all the warlords Crow met the one he actually struck up a friendship with was the twenty five year old ‘Commander in Chief’ Swen Miao. In Crow’s own words Swen was ‘a real throat slitting bandit of the sort that splash blood on the pages of fiction and sometimes get into Hollywood.’ Crow and Swen’s friendship reached the point where Crow sent cartons of cigarettes to him while the warlord sent Crow bottles of brandy, though Crow noted that while he paid for the cigarettes the brandy was undoubtedly part of the bandit’s swag from some looting expedition. The two eventually got to the point where Swen referred to Crow as dage, or elder brother. A rare privilege indeed.

The story of how Crow got to be such good friends with a bandit warlord was a major news story in Shanghai at the time. Swen was one of China’s best-known and most notorious bandits in the 1930s and made the front pages of newspapers as far afield as London and New York. Crow’s description of him as throat slitting doesn’t sit with the fact that Swen spoke English, was considered patient by his hostages and generally thought to be a good and kind leader of his men – JB Powell called him a ‘young chap…from a formerly respected family’. He had also received military training in the army of Chang Ching-yao, the pro-Japanese warlord who had taken control of Beijing briefly in 1920.

However, in the intervening decades Swen has largely been overshadowed in history by Chang Tso-lin, who was assassinated by the Japanese when his train was blown up in 1928 after forming an alliance with the Nationalists. Crow was forced to admit that Swen slipped pretty quickly from history: ‘He was not, however, a very successful bandit, for he was young and more ambitious than practical; but he might have travelled far after he had gained more experience if he had not been beheaded before he reached the prime of life.’

In fact Swen’s story was fairly typical of many bandits in China. He had come from a successful family who had managed somehow to annoy a local magistrate with their progressive political ideas. His father had ended up losing his head after a show trial on trumped up charges. The magistrate then made every police station in the family’s home province of Shandong exhibit photos of the execution and Swen was smart enough to realise that someone this obsessed with destroying his family would come after him next. So he wisely took to the hills with a few other endangered relatives and sought revenge on the magistrate. As Crow noted, ‘The Chinese learned many centuries ago that crooked officials can never be reformed and that the only practical thing to do is to kill them.’ At least that was the biography of Swen Crow believed. An alternative, somewhat less romantic version, has it that the Swen clan fell on hard times after idle, gambling sons squandered the family’s wealth and so became salt smugglers and bandits.

Whichever was the true story soon Swen had over 700 followers as his ranks swelled with men following the Yellow River flooding in 1920 and 1921 ruining many peasant farmers. Swen initially had a good stock of arms purchased with the proceeds of raids and robberies. However, the local population didn’t care that much as Swen mostly raided police stations or ambushed armed police detachments patrolling the countryside. As their loot grew many disaffected soldiers fed up with low pay and meagre rations joined Swen. Poor peasants worked their farms and then when the harvest was finished would disappear for a little banditry until farm work called them back to their land. Swen moved on to raiding rich landowners and became a Robin Hood figure for many peasants and perpetuated this myth of being an active agent of redistribution by naming his gang the Shantung People’s Liberation Society. All the time he kept on trying to assassinate the original corrupt magistrate who had killed his father though the man kept a loyal force of bodyguards that made the job difficult. As time passed so the Shantung People’s Liberation Society grew still further in a loose way with more bandits joining the ‘cause’.

Eventually the Liberation Society set up a semi-permanent camp on the slopes of Paotzeku Mountain, which was virtually unassailable from below. Swen continued raiding and kidnapping to the point where his reputation grew to such proportions that he rarely needed to leave camp and local merchants and wealthy landowners started paying him tribute and tolls (lijin) as protection money to leave them alone. The magistrate and his forces rarely entered Swen’s territory. It was a stand off between the secure Swen and the well-guarded magistrate.

This situation could presumably have carried on indefinitely to both men’s benefit had Swen not decided on 6 May 1923 to attack the nearby Tianjin-Pukow Railway and derail the new deluxe fast train that plied the route between Shanghai and Beijing, the Blue Express – the first all-steel train in Asia. Swen, and a thousand of his followers, kidnapped all the passengers in the early hours of the morning and looted the train near the town of Lincheng close to the Jiangsu-Shandong border (though technically in Hebei province) leading to the whole crisis becoming known as the Lincheng Outrage. His hostages included 300 Chinese and, crucially, 25 foreigners (foreigners generally fetched larger ransoms). The train was ransacked, all valuables taken and even the mattresses and light bulbs stripped by the bandits as loot.

One short-term hostage was First World War veteran and China Press journalist Lloyd Lehrbas who managed to escape and started filing stories about the incident almost immediately. Consequently the news that foreigners had been kidnapped from the Blue by a warlord and that a ransom was being demanded greatly excited the greatly excitable Shanghai foreign community many of who saw visions of Boxer-like retribution and killing returning. To the insulated residents of the International Settlement Chinese warlords terrorising and kidnapping Chinese citizens was one thing but terrorising and kidnapping westerners was quite another thing altogether. Though the kidnapped were probably relatively safe on the grounds that dead hostages were worthless it was not unknown for prisoners to be slaughtered wholesale by warlords. The bandit soldiers were a mixed bunch and included poor farmers and unemployed youth from the ‘university of the forest’ as well as a hard core of battle trained soldiers who had seen action in Russia and Korea as well as China but had been discharged from the Chinese army and were aggrieved at their loss of status as well as men who had formed part of the 140,000 strong ‘Chinese Labour Corps’ recruited by the British and French during the First World War to do tasks such as clearing the dead from the European battlefields and keeping the trenches supplied. Needless to say these men had seen some of the worst atrocities imaginable, become extremely battle hardened and then sent home with some coppers once their usefulness ended.

In news value terms kidnapping, of either Chinese or foreigners, was not necessarily a shocking event at the time. Crow described kidnapping as a ‘well organised business in China carried out with a large degree of success…’ although kidnapping was still something to be feared. Crow knew that travelling in the hinterland of China between the wars, as he did often, was to put yourself at a certain risk of kidnap whatever precautions were taken. Small comfort was the fact that it was relatively rare for foreign hostages to be abused severely and Crow worried more about lack of food and inclement weather than violent mistreatment.

The rest is in the book…!!

Leave a Reply