Roger Fry at Charleston #2 – Arthur Waley, Murasaki Shikibu, Virginia Woolf, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Charleston

Posted: January 5th, 2026 | No Comments »Talking about the Roger Fry exhibition at Charleston yesterday (details of that show here) it’s possible to dig a little deeper into Fry’s relationship with the English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry. Waley, from 1913 the Assistant Keeper of Oriental Prints and Manuscripts at the British Museum. Waley’s supervisor at the museum was the poet and scholar Laurence Binyon, and under his nominal tutelage, Waley taught himself to read Classical Chinese and Classical Japanese, partly to help catalogue the paintings in the museum’s collection. Despite this, he never learned to speak either modern Mandarin Chinese or Japanese and never visited either China or Japan – and never went east of Switzerland.

So, Waley lived in Bloomsbury and had a number of friends among the Bloomsbury Group, many of whom he had met when he was an undergraduate at Cambridge. Fry, somewhat older than most of the Bloomsburyites and Waley, would have been interested in Waley’s role at the British Museum and the China/Japan collections. Fry’s interest in things Chinese and Japanese was shared by the Bloomsbury Group. And so back to the Roger Fry Exhibition at Charleston, former Sussex home of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

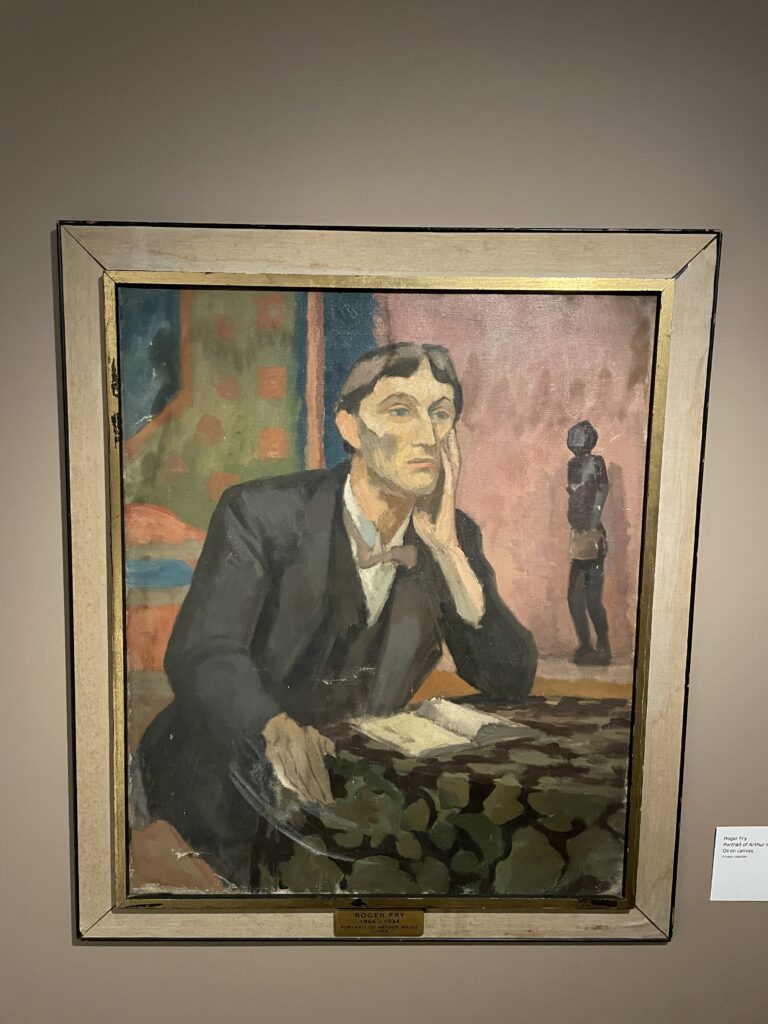

First here is Fry’s portrait of Waley… painted in 1915 when Waley was 26 and had recently (in 1913) joined the British Museum.

There’s another link to Waley and Charleston – in the house you can view The Famous Women Dinner Service, a collection of 50 hand-decorated plates by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, celebrating famous women throughout history, commissioned by art historian and museum director Kenneth Clark in 1932. The portraits – subdivided into Women of Letters, Queens, Beauties, and Dancers and Actresses – include George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, Elizabeth Barrett Browning; the Queen of Sheba and Elizabeth I; Dante’s Beatrice and the pre-Raphaelite Elizabeth Siddal; Greta Garbo and Ellen Terry. Many of these women lead complex and scrutinised lives, resisting marriage in favour of unconventional domestic arrangements and individual freedom.

One of these 50 hand-decorated plates, below, is of Murasaki Shikibu, ’Lady Murasaki’, a Japanese novelist, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial court in the Heian period best known as the author of The Tale of Genji, widely considered to be one of the world’s first novels, written in Japanese between about 1000 and 1012. And whose translation of The Tale of Genji do most of us as English speakers read? The Waley translations published in 6 volumes from 1921 to 1933.

Virginia Woolf championed The Tale of Genji, praising Arthur Waley’s 1925 translation in British Vogue, seeing Murasaki Shikibu as a literary ancestor for her focus on nuanced human life and emotion, rather than war or politics, though she critiqued its pacing compared to Tolstoy’s force. Woolf’s review significantly boosted the Japanese classic’s Western recognition, highlighting its psychological depth, beauty, and cultural insight, despite some contemporary racial exoticism and her incomplete reading of the text.

Jonathan Spence perhaps best expresses why we still read Waley’s translations:

‘…selected the jewels of Chinese and Japanese literature and pinned them quietly to his chest. No one ever did anything like it before, and no one will ever do it again. There are many westerners whose knowledge of Chinese or Japanese is greater than his, and there are perhaps a few who can handle both languages as well. But they are not poets, and those who are better poets than Waley do not know Chinese or Japanese. Also the shock will never be repeated, for most of the works that Waley chose to translate were largely unknown in the West, and their impact was thus all the more extraordinary.’

(of course Spence should have said ‘in English’ rather than ‘in the West’ as others like Judith Gautier in France were also translators with language skills and poet skills).

And so Bell and Grant were extremely familiar with Lady Murasaki and Waley’s translation of The Tale of Genji…

Leave a Reply