Mekong Review – November 2021-January 2022 Issue

Posted: November 3rd, 2021 | No Comments »The new issue of the Mekong Review does include a light-hearted piece by me on British “Big Beast” authors and their close or distant relations with China in the 1930s. However, there’s a lot more too….

| A thread of both resistance and disappointment runs through this issue of Mekong Review, illustrating how much has changed across the region in the six years since this publication first appeared on newsstands. Democracy and openness have been under relentless pressure across the region: in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand and elsewhere. China has retreated into a threatening neo-Maoism and India into religious bigotry. Behind it all the climate emergency and environmental degradation threaten everyone. |

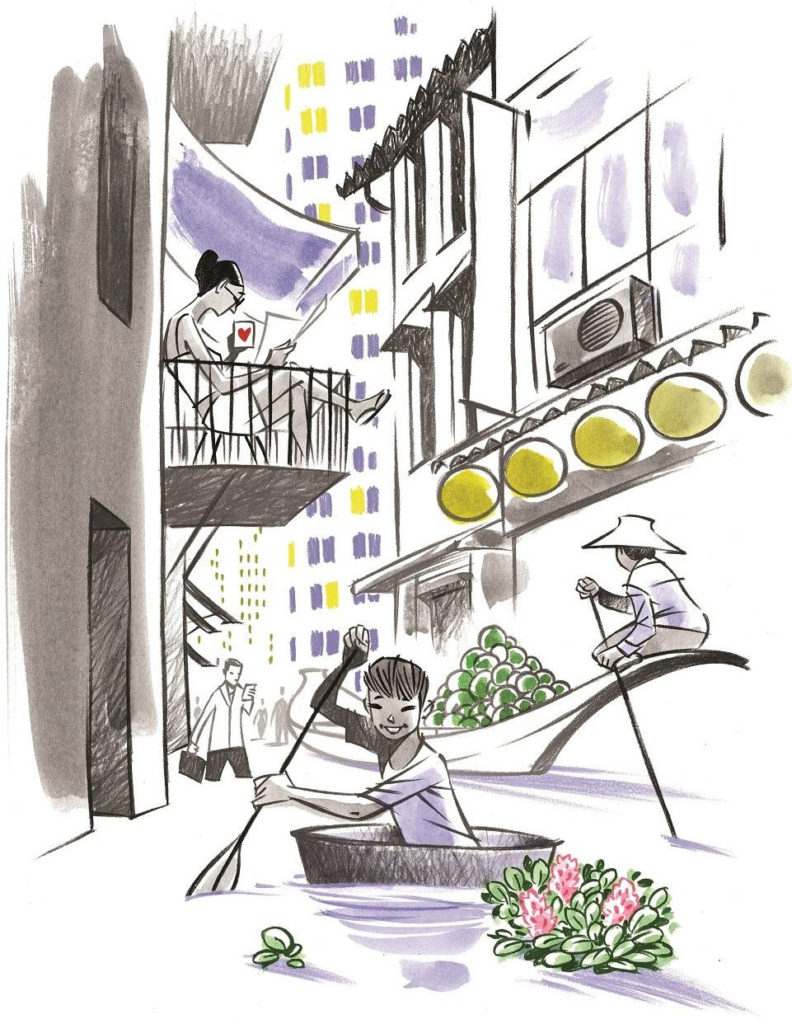

| Amitav Ghosh, the Indian writer who has emerged as a key thinker on climate, colonialism and the consequences of ignoring our relationship with nature, discusses his new book, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. The Spice Islands were once what Ghosh calls ‘the fulcrum of world trade’, enriching the Netherlands at the cost of people’s lives. Colonial violence is embedded in the memories of those who live in what is now a remote part of Indonesia, but it is rarely told. And when it is told, it is unclear if it makes a difference. The forgotten stories of South Vietnam, a nation built up and then abandoned by the United States, are the subject of an essay by Anthony Morreale. While the literature of the victors from the North has been translated and admired in the past few decades, that of the South has been mostly forgotten, a lonely memory for a diminished number of the Vietnamese diaspora. ‘Whatever the cause, most contemporary Vietnamese literary critics agree that South Vietnam produced some of the best Vietnamese literature ever written, far better than what was coming out of the North at that time.’ Greater freedoms in the South created an environment in which writing was not just yoked to the cause of war; instead, it dug into the stories of the postcolonial world. Politics in Cambodia, the Philippines and Thailand are much like Tolstoy’s families—all unhappy in their own ways. Colin Meyn examines the turn towards authoritarianism of Cambodia and the shaky prospects for Hun Sen’s planned dynastic succession. Richard Heydarian writes of the ‘murderous populism’ under Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines. Applying both humour and violence in equal measures, Duterte is oblivious to taboos, according to a new study by Vicente L. Rafael, a Philippine-born historian at the University of Washington. Duterte nonchalantly jokes about rape and murder, describing the killing of drug dealers as ‘beautiful’. It’s a language the world also knows from Trump, Putin and their ilk. In Thailand, King Bhumibol made a point of never smiling; there were few shows of public humour, even of the black Duterte variety. Wasana Wongsurawat examines how the king’s interventions in politics still haunt Thai politics, buttressing a political order, external to the constitution, that keeps the monarchy and conservative forces in power. Suhasini Patni profiles Meena Kandasamy, a Tamil writer whose latest book, The Orders Were to Rape You, reveals the stories of women who took up arms against the Sri Lankan state during the long civil war there. The role of women in war has come to the fore in the works of a number of women writing about Sri Lanka and other conflicts. Their politics, voices and opinions are brought out in Kandasamy’s works with their full intent; they are no longer writers of laments or passive victims of violence but participants in the struggle. Three Tamil poets translated in the book ‘embody a radical departure from convention’. There may be resistance, but there has been a lot of disappointment about the retreat of democracy in so much of Asia and the violence that has been inflicted. Lok Man Law captures the exhaustion and sadness of Hong Kong as repression deepens and many people move towards internal exile, the state in which any diversion from political reality is welcome. ‘When you accidentally see the news on a TV in one of the old-style neighbourhood cafés, every word and image seems to scrape your skin raw and make your scalp prickle.’ Prison, emigration or internal exile are the options as democracy is choked. There are birds in Myanmar and Cambodia, life in Salt Lake near Kolkata, Australia’s fearful relationship with China, and poetry from Thailand, India and Hong Kong. Debut novels are featured from Emma Larkin and Avni Doshi. Anthony Tao laments the loss of street food in Beijing as vendors are swept away in the name of hygiene and pollution control. Far too many aspects of our lives are going the way of the Henanese vendor of grilled meat: ‘One day, he wasn’t there—and he’s never been since.’ Subscribe or find a list of stockists here |

Leave a Reply