Posted: January 29th, 2018 | No Comments »

A short piece I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel wishing au revoir to the Astor House Hotel and remembering some of its characters and literary moments….click here…

Posted: January 26th, 2018 | No Comments »

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China publishes original research articles of up to 10,000 words on topics on Chinese culture and society, past and present, with a focus on Mainland China. All articles, including peer-reviewed, must be original and previously unpublished, and make a contribution to the field. The Journal also publishes timely reviews of books on all aspects of Chinese history, culture and society. The Journal’s publication frequency is once annually in print and online.

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China is a continuation of the original scholarly publication of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, the Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, published 1858 – 1948, and recommenced in 2010. The Journal proudly maintains the level of academic standards and innovative research that marked its standing as the preeminent Western sinological journal in China for nearly a hundred years.

– All articles should be written in Word format for our editorial panel to open, read and edit. The font should be Times New Roman, 12 point. The title of your article should be in bold at the beginning of the file, but not enclosed in quote marks. Bold is also used for headings and subheadings (which should also be in Times New Roman, 12 point) in the article. Articles should be 8,000 to 10, 000 words, and must not exceed the 10,000 maximum word count, which includes notes and references – but does not include the author bio and abstract. (For shorter articles, please receive pre-approval from our editorial panel.) Book reviews are to be between 1,000 to 3,000 words and must not exceed 3,000 maximum word count.

– Please use the Chicago Manual of Style, but articles must be submitted in British English. Pagination should be on the top right corner.

– All articles must include an abstract of up to 250 words.

– Images: You may submit colour images, which will be available for online version only. In print, the images will appear in black and white. All images need a resolution of at least 300 dpi. All images should be supplied independently of the article, not embedded into the text itself, in jpeg format. The files should be clearly labelled and an indication given as to where they should be placed in the text. Images sent in as e-mail attachments should accordingly be in greyscale. The image should always be accompanied by a suitable caption. The following is the agreed style for captions: Figure 1: Caption here. Please note the colon after the number and the terminating full point, even if the caption is not a full sentence. It is the responsibility of the author to secure image permission rights and present the consent letter in the submission.

– The copyright consent form giving us your permission to publish your article must accompany your submission. Please obtain the RAS China copyright consent form after your article is pre-authorized for publication.

– Please include author’s bio of up to 50 words with an email address. Do not include CV or self-portrait photo. If a bio is not submitted, it will not be printed.

– Articles submitted to the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society should be original and not under consideration by any other publication, unless pre-authorized by our editorial panel. If the article is a reprint, it is the sole responsibility of the author to obtain all permissions including text, images and present necessary consent forms with the submission.

Please ensure that your manuscripts meet these requirements. Also, be advised that the RAS Journal is a non-profit publication and does not provide writer’s fee.

Submission deadlines:

– Abstract submission for pre-authorization: 20 January to 30 March 2018 – Manuscript submission final deadline: 1 May 2018

Projected publication timeframe: Late August 2018

Please send inquiries and abstract to the Journal’s Honorary Editor, Julie Chun: editor@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

Posted: January 25th, 2018 | No Comments »

1937 advertisements in the British press for Ceylon winter breaks…cold January in London makes it very attractive – then and now….

Posted: January 24th, 2018 | No Comments »

In December 1937 The Spectator recommended this as a great Christmas read….huumm??!! Cyril Northcote Parkinson was a British naval historian and author of some 60 books. He had worked in Singapore for some time in the University of Singapore and was influential in establishing an (at the time) very modern history of Malaya course….

Parkinson himself

Posted: January 23rd, 2018 | No Comments »

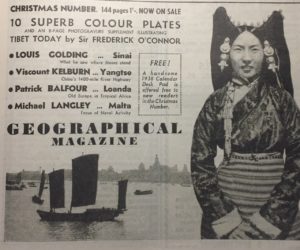

Following on from my post about occult explorer Theodore Illion yesterday and his supposed secret underground city in Tibet (published in 1937), here’s a 1937 ad for Geographical Magazine, the magazine of the Royal Geographical Society (then quite a new title – it’s only launched in 1935 I think) with a photo-spread on Tibet by Sir Frederick O’Connor. O’Connor was a military man, interpreter, explorer, author and several times visitor to Tibet. He was indeed Younghusband’s interpreter having lesarnt Tibetan while assigned to the India department. He seems to have made many friends in Tibet, including the Panchen Lama, hence his repeat visits…..

O’Connor driving his Peugeot “Baby” in Gyantse, Tibet in 1907

Posted: January 22nd, 2018 | No Comments »

Another little advert from the book pages of The Spectator in 1937…this one for Theodore Illion’s In Secret Tibet – yours for five shillings.

Illion is an interesting character – he claimed to have travelled to Tibet in the 1930s and discovered a vast underground city there – the secret in Secret Tibet. He later wrote a number of other books on Tibetan mysticism and traditional medicine – making great claims for both. IN Secret Tibet was originally published in German in 1936 and then in English in 1937. Illion is somewhat mysterious – claiming to have been born in Canada to a lost branch of the English Plantagenet royal family. Others say he was just a German obsessed with the occult and esoteric. He claimed to have lived undiscovered in Tibet – in disguise – and to have witnessed all manner of black magic (to be generous maybe he was there and saw shamans) and cannibalism all in this secret underground city that even above-ground Tibetans didn’t know!

(Illion)

(Illion)

The book was sold in England largely through William Rider and Son, a company that was formed in 1908 in London taking over the previous list of the occult publisher Phillip Wellby. They published everything from guides to tarot cards, cheaper edition of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Illion. Interestingly the Rider imprint still exists and is now part of Ebury, itself part of Penguin-Random House. Ridr still have a slight esoteric bent (a bit more palatable as New Age these days) and also publishes a range of stuff from Desmond Tutu to North Korean defectors…

Posted: January 21st, 2018 | No Comments »

Elizabeth Macguire’s book about Chinese in Moscow in the 1920s to the 1960s looks very interesting….

Beginning in the 1920s thousands of Chinese revolutionaries set out for Soviet Russia. Once there, they studied Russian language and experienced Soviet communism, but many also fell in love, got married, or had children. In this they were similar to other people from all over the world who were enchanted by the Russian Revolution and lured to Moscow by it.

The Chinese who traveled to live and study in Moscow in a steady stream over the course of decades were a key human interface between the two revolutions, and their stories show the emotional investment backing ideological, economic, and political change. They embodied an attraction strong enough to be felt by young people in their provincial hometowns, strong enough to pull them across Siberia to a place that had previously held no interest at all. After the Revolution, the Chinese went home, fought a war, and then, in the 1950s, carried out a revolution that was and still is the Soviet Union’s most geopolitically significant legacy. They also sent their children to study in Moscow and passed on their affinities to millions of Chinese, who read Russia’s novels, watched its movies, and learned its songs. Russian culture was woven into the memories of an entire generation that came of age in the 1950s – a connection that has outlasted not just the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the collapse of the Soviet Union, but also the subsequent erosion of socialist values and practices. This multi-generational personal experience has given China’s relationship with Russia an emotional complexity and cultural depth that were lacking before the advent of twentieth century communism – and have survived its demise. If the Chinese eventually helped to lead a revolution that resembled Russia’s in remarkable ways, it was not only because class struggle intensified in China due to international imperialism as Lenin had predicted it would, or because Bolsheviks arrived in China to ensure that it did. It was also because as young people, they had been captivated by the potential of the Russian Revolution to help them to become new people and to create a new China.

This richly crafted and narrated book uses the metaphor of a life-long romance to tell a new story about the relationship between Russia and China. These lives were marked by an emotional engagement that often took the form of a romance: love affairs, marriages, divorces, and <“love children,>” but also inspiring revolutionary passion. Elizabeth McGuire offers an alternative to the metaphors of brotherhood or friendship more commonly used to describe international socialism. She presents an alternate narrative on the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s by looking back to before the split to show how these two giant nations got together. And she does so on a very personal level by examining biographies of the people who experienced Sino-Soviet affairs most intimately: Chinese revolutionaries whose emotional worlds were profoundly affected by journeys to Russia and connections to its people and culture.

Posted: January 20th, 2018 | No Comments »

Yesterday I blogged an advert for Ella Maillart’s Forbidden Journey (1937) – today the cover art from various editions over the decades….