Posted: December 13th, 2017 | No Comments »

Well deserved…a great book….

Dr Edward Denison and Guang Yu Ren for Ultra Modernism in Manchuria

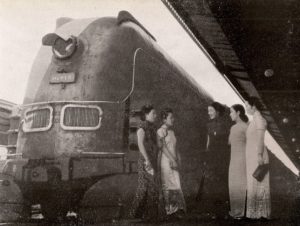

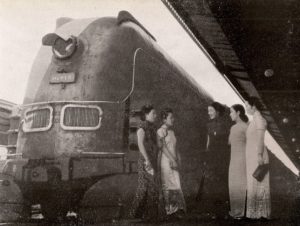

The Asia Express, the South Manchuria Railway’s ‘ultra-modern’ high-speed train at Dalian’s ‘ultra-modern’ railway station with ‘ultra-modern Manchurian girls’.

The Asia Express, the South Manchuria Railway’s ‘ultra-modern’ high-speed train at Dalian’s ‘ultra-modern’ railway station with ‘ultra-modern Manchurian girls’.

The awards celebrate the best research in the fields of architecture and the built environment.

The 2017 RIBA President’s Medal for Research was presented to Dr Edward Denison Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL and Guang Yu Ren, Independent Researcher, UK for their project: Ultra Modernism in Manchuria.

The paper explores ‘Ultra-Modernism’, an ideological term employed to describe Japan’s encounter with modernity and its distinction from western precedents/constructed cannons, deemed historically and intellectually impartial.

‘Ultra-Modernism’ refers to the speed and intensity of the development of the north-eastern region of China formerly known as Manchuria before the Second World War, when Japan’s attempts to build an empire throughout the 1930s prompted the construction of more than one hundred towns and cities in a new state they named Manchukuo.

about the book:

History is a record of power. The twentieth century – modernism’s century – was dominated by ‘the west’ and its ‘official’ history is a testament to this dominance of ‘others’.

Modernist history is a canon constructed by, for and of the west, with major consequences for architectural encounters with modernity outside the west, which are routinely overlooked or possess an assumed inferiority; a postulation asserted through inauthenticity, belatedness, diluteness and remoteness, geographically, intellectually, and even racially. Few sites demonstrate this historical and intellectual impartiality more explicitly than the north-eastern region of China formerly known as Manchuria before the Second World War, when Japan’s attempts to build an empire throughout the 1930s prompted the construction of over one hundred towns and cities in a new state they named Manchukuo.

Such was the speed and intensity of Manchukuo’s encounter with modernity and its distinction from western precedents, the Japanese branded it ultra-modernism. Ultra-Modernism in Manchukuo was ideologically ubiquitous and became manifest in urban planning, architecture, transportation, photography and film – all essential facets of modern metropolitan life in Manchukuo.

Among the many new cities developed by the Japanese, the jewel in their imperial crown was the vast new capital of Hsinking (‘New Capital’), the city’s nomenclature echoing the ultra-modernity on which empire was built. Despite the scale, scope and consequences of Manchukuo’s encounter with modernity, its experiences have yet to make a significant contribution to architectural knowledge globally.

After more than a decade of research culminating in the recent publication of the first book to focus exclusively on architecture and modernity in Manchuria, this work not only fills a conspicuous gap in existing architectural knowledge and challenges the modernist canon, but also provides important context to the rising tensions in the region, the seeds of which were sown in Manchuria.

Posted: December 11th, 2017 | No Comments »

Please join our tour of Fayuan Temple, the oldest Buddhist Monastery in Beijing, led by cultural heritage protection expert Matthew Hu Xinyu.

First built in the Tang Dynasty (645 AD), during the reign of Emperor Taizong, the temple was rebuilt a number of times over the centuries. Many of its historical relics survived through the ages, even though the temple was severely damaged during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution. The Fayuan temple is also known as the backdrop for an historical novel, titled “Martyrs’ Shrine: the Story of the Reform Movement of 1898 in China†and written by prominent author Li Ao, who was born in Beijing and brought up in Taiwan; it was a Nobel Prize for Literature nominee in 2001. A national-level listed heritage building, the temple currently hosts the China Buddhist College and the China Buddhist Sutra Library.

Date:Â Â Friday, Dec 15, 2017

Time:  2 pm – 4:30 pm

Where: Fayuan Temple, #7 Fayuansi Qianjie (south of Jiaozi Hutong), Xicheng District tel: 6353 4171 (15 mins walk from Caishikou subway stop, exit D) 西城区法æºå¯ºå‰è¡—七å·æ³•æºå¯º

How much: RMB 50 for RASBJ members, RMB 80 for non-members (prices include the entry fee)

RSVP: email communications.ras.bj@gmail.com no later than Dec. 14, and write“Fayuan Temple†in the header.

Posted: December 9th, 2017 | No Comments »

Camphor Press has published Aso Tetsuo’s war diary, From Shanghai to Shanghai….

“My war records are of military comfort women…â€, writes Dr. Aso, “…cabaret dance girls, the military secret service, missionaries, and . . . the incidentâ€. The “incidentâ€, as it is often referred to in books about Japanese comfort women, alludes to the fact that Dr. Aso (1910–1989) was the first Japanese medical officer officially ordered to perform health examinations on military comfort women. This policy was instituted in 1937 for a new contingent of comfort women freshly sent to Shanghai to serve the Japanese military. It was the initial measure undertaken by the Japanese High Command to reduce venereal disease among the troops. Dr. Aso performed this duty throughout the term of his assignment in China.

From Shanghai to Shanghai (Shanhai yori Shanhai e) is the most unusual, grass-roots diary of Dr. Aso, a 27 year-old gynecologist who takes us with him to work and on his travels throughout China during his various tours of duty in the Sino-Japanese war. The journey begins in late 1937, when he first arrived in Shanghai, and continues for four years, until 1941, when he returned to Japan from Shanghai after tours of duty in Shanghai, in Nanjing, and in a number of other parts of central China.

Dr. Aso Tetsuo was quite literally born into a world of gynecology and prostitution. His father was a gynecologist with a private medical and teaching practice in the “entertainment quarters†— red light district — of Fukuoka. Besides being a school for midwives, Aso’s childhood home was a medical clinic for the prostitutes employed in the neighboring teahouses and brothels. As a child, Aso knew the women who were his father’s patients as his “big sistersâ€. It was only natural, Aso later reflected, that when he grew up he would become a gynecologist and specialize in the health of working women. After the end of the war in 1945, Aso was frequently accused by the press of having forced women into prostitution during the war. This prompted him finally to tell his side of the story by compiling this remarkable book from his wartime diary.

Posted: December 8th, 2017 | No Comments »

The BBC’s new adaptation of Howards End was generally well received. For China Rhyming readers the last episode may elicit a slight raising of the eyebrow as Tibby Schlegel proudly displays his grasp of Chinese to his sister Margaret and displays well-thumbed, Chinese Grammar as he sits by the fire practicing his tones.

Tibby is in his final year at Oxford and “glancing” at his Chinese Grammar in case he should decide to try for a Student Interpreter post with the Foreign Office (as the lowest rung of the China Service was called – you moved from interpreter up the ranks). In the BBC version Tibby tries out a bit of Chinese on his sister – in Forster’s novel (1910) he merely studies it and keeps his tones to himself.

Tibby might have been immersed in the Reverend Donald MacGillivray’s A Mandarin-Romanized Dictionary of Chinese, probably the Chinese Grammar of choice for Edwardian scholars before the First World War. There are alternatives though and most likely for Tibby’s level of interest was Walter Craine Hillier’s The Chinese Language and How to Learn It (1907 – below). The book was very popular with language students and the generally interested early in the twentieth century.

Posted: December 7th, 2017 | No Comments »

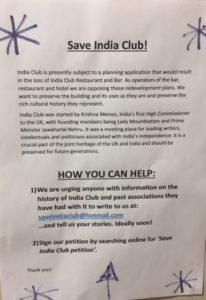

A little deviation from China today, but an important one. The India Club on London’s Strand is an institution – not one for the super rich and wealthy, the particularly fashionable or the jet-set crowd. Rather it’s a place in the West End without pretensions that hasn’t changed much in nearly 70 years. To walk into the India Club (and anyone can) – the bar on the first floor and the restaurant on the second floor are a little whiff of the 1940s. It does quite good business despite being irredeemably old fashioned – barristers from the nearby chambers and law courts, academics and students from King’s, those who know their West End beyond the chains and the fly-by-night trendy eateries.

The Club has links to Krishna Menon (a former editor at Penguin Books and later India’s first High Commissioner to London) – Nehru and Lady Mountbatten were early members and patrons. The entire building was The Strand Continental Hotel at one point – and indeed part of the building is still a budget hotel. And so, of course, it’s under threat from developers and, of course, the developers want to rip it all out and create God only knows what horror. So there’s a campaign – see below….sign the petition, have a moan and then, if you haven’t, go and have some food and a beer and support them.

Posted: December 6th, 2017 | No Comments »

Not particularly China, but hopefully of interest to some…

I’ve probably read more crime this year than any other – writing the fortnightly Crime and the City column for The Literary Hub, the occasional article and review for the UK magazine Real Crime and various other bits and pieces of reviewing have all added up to a lot of reading. Much of it of course is not newly published but these are, to my mind, the best…

The Dry – Jane Harper’s debut novel was a master class in small-town tension in the Australian outback.

Police at the Station and they Don’t Look Friendly – Adrian McKinty is just firing on all cylinders with the Sean Duffy series and this, the sixth Duffy book, shows their plenty of mileage left.

The Long Drop – Denise Mina gave true crime literary non-fiction a go and triumphed in this tale of one long drunken Glasgow night with the serial killer Peter Manuel and his associates.

The Shadow District – Arnaldur Indridason’s first historic crime novel (I think) – Reykjavik in WW2 and a city full of American GIs with murder in the town’s darkest back alleys.

The Man Who Wanted to Know – D.A. Mishani’s latest Tel Aviv-set crime novel repeats his previous trick of making seemingly mundane lives in the blandewst of suburbs fascinating.

The Pictures – Guy Bolton’s period piece with an LAPD cop who’s covered up crimes for the Hollywood studios reaching his own personal breaking point.

A Necessary Evil – Abir Mukherjee’s second Sam Wyndham of the Calcutta Police in post-WW1 India tale hit the mark again with the second in what should be a great continuing series.

The King of Fools – Frederic Dard’s novella is not new, but it is new in English. Pushkin Press are translating a few new Dard books a year and, if you like your crime deep noir and consumable in one sitting, then Dard is the master.

The Force – Don Winslow did it again – ‘nough said really.

I would also note that espionage had a good year. John Le Carre’s A Legacy of Spies of course – Smiley returning was always going to be a big event; Adam Brookes’s Mangan trilogy completed with The Spy’s Daughter; and Joseph Kanon’s Defectors proved he is still top of the game.

On TV it was a sad farewell to Ripper Street matched only by an eager hello to The Deuce (episode 7 written by noir maestro Megan Abbott stood out as exceptional) while we kept right on with the Shelby clan and Peaky Blinders. I also enjoyed the Danish show Norskov, got pretty obsessed about the French show Mafiosa (set in Corsica), thought The Last Post (which had some criminal activity) from the BBC better than the critics did, and binge-watched the latest series of Bosch, the adaptation of Michael Connelly’s novels. I am, as we speak, right in the middle of the excellent Babylon Berlin and need to get back to it now. So that’s that for 2017.

Posted: December 5th, 2017 | No Comments »

The excellent London Fictions website has posted an article by Anne Witchard on MP Shiel’s 1898 The Yellow Danger…..(the entire article here)

China in the Western imagination has long been both the repository of fantasy and a mirror of our disquietudes. In the early twentieth century Sax Rohmer created the fiendish Dr Fu Manchu as the epitome of Chinese threat, ‘the yellow peril incarnate in one man’ intent on nothing less than the downfall of Western civilization.

​

Even beyond its cohort of unrepentant fans and equally vociferous detractors, Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series (beginning in 1912) sustains a cultural longevity that merits our attention. That this dated generic phenomenon has now outspanned the century of its birth might be attributable to the fact that Rohmer’s super villain actually has his imaginative genesis in the 1890s. The closing decade of the Victorian era is redolent with metropolitan associations that remain iconic: Hansom cabs and Sherlock Holmes, mummy curses and murky gaslight, a visiting vampire count and Jack the Ripper.Â

We might date the start of an obsession with a Yellow Peril in British popular culture from 1898, its most notable marker being the publication that year of M. P. Shiel’s novel, The Yellow Danger.

Click here for the rest of the article

Posted: December 4th, 2017 | No Comments »

Renowned Hong Kong historian Tony Banham’s new book on the evacuation of allied women and children from Hong Kong in 1940…Reduced to a Symbolical Scale…

In July 1940, the wives and children of British families in Hong Kong, military and civilian, were compulsorily evacuated, following a plan created by the Hong Kong government in 1939. That plan focused exclusively on the process of evacuation, but issues concerning how the women and children should settle in the new country, communication with abandoned husbands, and reuniting families after the war were not considered. In practice, few would ever be addressed. When evacuation came, 3,500 people would simply be dumped in Australia.The experience of the evacuees can be seen as a three-act drama: delivery to Australia creates tension, five years of war and uncertainty intensify it, and resolution comes as war ends. However, that drama, unlike the evacuation plan, did not develop in a vacuum but was embedded in a complex historical, political, and social environment. Based on archival research of official documents, letters and memoirs, and interviews and discussions with more than one hundred evacuees and their families, this book studies the evacuation in its full context.

The Asia Express, the South Manchuria Railway’s ‘ultra-modern’ high-speed train at Dalian’s ‘ultra-modern’ railway station with ‘ultra-modern Manchurian girls’.

The Asia Express, the South Manchuria Railway’s ‘ultra-modern’ high-speed train at Dalian’s ‘ultra-modern’ railway station with ‘ultra-modern Manchurian girls’.