Posted: July 10th, 2017 | No Comments »

Since its earliest days as a treaty port Shanghai always used sprinklers on its streets – a big help when horse and cart was the main conveyance and equine pee was a major problem that needed washing away. 1932 though and Shanghai does away with its old horse and cart watering carts and introduced motorised sprinklers. Just in time too – when trouble with the Japanese came and the Settlement needed defending the American Marines turned the sprinkler cart into their water wagon.

Posted: July 9th, 2017 | No Comments »

‘Shanghai this and Shanghai that’…so true now, and then – 1933 to be exact. Of course Shanghai Madness was not Spencer Tracey’s best movie by a long way and Shanghai Orchid never got made.

However, the article was right – audiences had seen Dietrich and Anna May Wong smoking in Shanghai Express (1932), Mack Sennet’s Shanghai Love (1932), Mary Nolan in Shanghai Lady (1929), Richard Dix in Shanghai Bound (1927), Conrad Nagel in Ship From Shanghai (1930), Hichcock’s East of Shanghai (1931) and an Anna May Wong movie called Streets of Shanghai (1927) as well as probably a few I’ve forgotten….

Throw Shanghai in the title and hope for the best….and we still had Shanghai Gesture and a whole bunch more to come.

Posted: July 8th, 2017 | No Comments »

I’m sure you’ll agree that Miss Beatrice Gracey looks like a woman who knows her mind; makes her decisions and sticks to them.

She was of strong stock – Beatrice’s father was S.P. Gracey, who was a banker and member of the Shanghai Stock Exchange but had been in Shanghai in various posts, including with the American Trading Company, since the early part of the century.

Beatrice left the University of California and returned to Shanghai in 1930. She then took a job with the US Consulate in Hankow (Hankou) and along the way met D.W. Morrison, a Scottish oilman based in China working for the Asiatic Petroleum Company.

Obviously they fell in love and Beatrice travelled from China to San Francisco, then across country to New York and then another ship to Southampton before a train up to Inverness in Scotland where she married D.W. Morrison at his ancestral home.

I believe the couple returned to China and that Beatrice was interned for the duration of the war in Chapei camp in Shanghai.

Posted: July 7th, 2017 | No Comments »

This month in 1933 heralded the official opening of the Shanghai-Hangchow (Hangzhou) Highway (what is now the G92 or something I think), all 320 miles of it…and so the West Lake became a road trip tourist attraction from Shanghai….

Posted: July 6th, 2017 | No Comments »

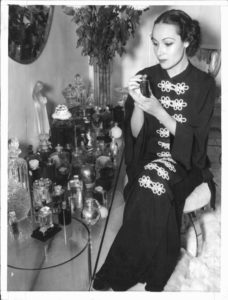

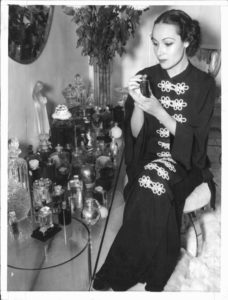

Here we have the beautiful Mexican movie star Delores Del Rio examining her extensive perfume collection and enjoying some chinoiserie style – the low chignon hairstyle and the knot-work gown.

Where did Delores get a taste for chinoiserie? Well it was in the air of course in the 1930s but she did make one China-related movie – 1938’s International Settlement (referring of course to Shanghai) – it’s no Shanghai Gesture but it ain’t bad, largely due to Del Rio: “In Shanghai amidst Sino-Japanese warfare an adventurer (George Sanders) collecting money from gun suppliers falls in loves with a French singer (Delores Del Rio).” The supporting cast is not too exciting though Keye Luke (see my posts about him and his art work here) appears.

As far as I know Del Rio never actually went to China – International Settlement was shot on the 20th Century Fox Studios lot on Pico Boulevard in LA. But still…enjoy…

Posted: July 5th, 2017 | No Comments »

Yet another plan to muck about with Suzhou Creek – and, as usual, much of the plan is based on rather spurious information. Anyone reading an article (such as this in the every loyal Shanghai Daily) about redevelopment in Shanghai that suggests there will be a people-centred or heritage preservation element knows that as soon as the phrase “upmarket riverside community” is invoked we’re in for trouble. Since the 1990s great swathes of the banks of both the northern and southern side of the Creek have been redeveloped. This has involved 1) mass clearances of shikumen (invariably described as sub-standard or slums by the media) and 2) anonymous new gated tower block compounds that restrict access to the bankside. it is perhaps worse upstream, particularly when you get up around the old Jessfield area and what is now Zhongshan Park and beyond, but has been creeping ever eastwards over the years.

Worrying of course is that, for some unknown reason, the project keeps talking about the Suhe “Bay Area. Shanghai has rivers, creeks, brooks (mostly covered over now), lakes (mostly manmade), docks (mostly defunct), wharves (mostly unused) and docks. It does not have a bay (that would be Manila, or San Francisco you’re thinking of). And if it does have a bay that I don’t know about then it’s not halfway up Suzhou Creek!! The article refers to the “shantytown” of the area, another trigger to get you to think it’s all just slum fit for demolition.

In fact the area now being described as Suhe Bay Area comprises about 500,000 square meters of residential area. Actually already a bit less than 500,000 because they included the Sinza area, which is in the process of being pulled down with all its historic past ignored completely (see my post on that here). Consider that number – 500,000sqm. Sounds like a lot? Well consider that just in the last couple of years 920,000 square meters of residential – mostly shikumen from the 1920s – have been destroyed from the Creek as far north as Beijing Lu and an equal distance inland on the northern side of the river. 300,000 families have already been moved; a further 5,000 families will be moved by summer’s end – presumably their faces don’t fit the planned “upmarket riverside community”?

Of course a few large and stand out buildings will remain – the Embankment Building, former International Post Office, the Sihang Warehouse (now a museum) but the shikumen will probably all go. This of course leaves a totally unbalanced neighbourhood and architectural legacy. The new bridges over the Creek – 18 planned of which at least ten will be for traffic – are a disaster for anyone with plans to limit traffic in central Shanghai – more pollution, more accidents, more gridlock. The Creek doesn’t need anymore bridges.

Over the last quarter century (and a bit more) the banks of Suzhou Creek have been pecked away at and nibbled by property developers. Nothing of any architectural merit has been built along the Creek since the late 1930s. If this nonsense about the Suhe Bay Area is followed through (and nothing in Shanghai’s disastrous legacy of heritage abuse indicates it won’t) that will be the end of Suzhou Creek both as a vibrant central artery of the city and a community. It will become a vast gated community for the wealthy to closet themselves in surrounded by gridlocked traffic.

A sad end to once great waterway. Now stand back as the European and American architectural firms scramble unseemly for a contract and ignore all of the above….

Posted: July 4th, 2017 | No Comments »

The American steamer City of Peking sailed from Yokohama in January 1893 with a crew of passengers and cargo. All was good for ten days and then the shaft broke and the ship was forced to complete the journey under sail in gale force winds. After 15 days battling the winds under sail and with no engines they made it home. Missing, assumed sunk, San Francisco had been in mourning for the passengers and crew and then the City of Peking reappeared….

Posted: July 3rd, 2017 | No Comments »

You may recall that last month Xinhua was abuzz with talk of a restored brook in the Qianmen District of Peking. I wasn’t convinced such a brook existed to be restored in that area and no maps at my disposal showed any trace. I suggested it might be a fake brook. Well why not we have fake hutongs, fake shikumen, fake temples, fake colonial villas, fake art-deco so why not a fake brook? But there was a real brook, back in the Ming Dynasty….Jeremiah Jenne, a Beijing historian who knows far more than I do about the city, tracked it down – full story here in The Beijinger.