Posted: March 27th, 2017 | No Comments »

I’ve blogged a fair bit on the Chinese Labour Corps in WW1 so perhaps some readers may be interested in this event…

Chinese Labour Corps Project Launch Event – 19th April 2017

On 19th April, 1917, after a three-month journey over land and sea, a thousand Chinese men arrived in Le Havre, France, weary and bewildered. This was the first batch of the Chinese Labour Corps, recruited by the British to provide logistical help to the Western Allies. They would be followed by several tens of thousands, mainly from Shandong Province, thus forming one of the largest labour corps involved in the Great War.

To mark this historically significant event, exactly one hundred years later on 19th April, 2017, The Meridian Society, with SOAS China Institute as host, will be holding a film screening and talks to launch our heritage project on the Chinese Labour Corps, with the support of a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The key resource is a collection of unique interviews with CLC descendants from Shandong. Their distinctive memories have been captured on camera and at this launch, guests will be able to view for the first time, a public screening of the documentary ‘Forgotten Faces of the Great War’, containing oral histories by descendants both of Chinese labourers and Western CLC officers.

Alongside the screening will be talks by eminent speakers

(Chaired by Lars Laaman SCI) including:

– Frances Wood, Author of Author of ‘Betrayed Ally’, former Curator of Chinese Collections at the British Library and Research Associate at SOAS China Institute;

– Dominiek Dendooven, Curator at In Flanders Fields Museum;

– Andrew Fetherston, Archivist at Commonwealth War Graves Commission and

– Zhang Yan The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

A small display of items, including photos, documents and memorabilia, will be on show.

We will also be announcing details of the Society’s year-long series of activities to commemorate the CLC.

The event will be brought to a close by a Ceremony for the Departed conducted by Representatives of the London Fo Guang Shan Temple.

We hope you will be able to join us for this special event.

Please reserve your place no later than Wednesday 22nd March by replying to The Meridian Society at chineselabourcorps@gmail.com

Date: Wednesday, 19th April Time: 2.00-6.00pm

Venue: Djam Lecture Theatre (DLT)

SOAS University of London, Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG Entry: Free, but places must be booked in advance

Posted: March 26th, 2017 | No Comments »

Early Photographs of Hong Kong 1860 – 1927

a collection of original photographs

including a selection of fine original panoramas

of the waterfront and the harbour

Â

on Thursday 30th March 2017, 6.30 – 8.30pm

The exhibition continues until Saturday 29th April 2017

Wattis Fine Art

20 Hollywood Road, 2/F, Central, Hong Kong

Gallery open: Monday – Saturday 11am – 6pm

Posted: March 25th, 2017 | No Comments »

Here’s the programme for the 2017 Asia House Literary Festival this May in London with a bunch of good events (including me with Suki Kim on North Korea – more to follow on that….

Details of all events here. China Rhymers will probably be most interested in Xiaolu Guo on her new autobiography; Choo Waihong and Isabel Hilton on the Mosu and Zhang Lijia on Shenzhen hookers!

Posted: March 24th, 2017 | No Comments »

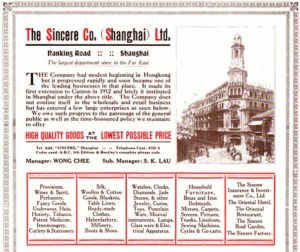

This advertisement for Sincere Department Store is from 1930 though the store had already been open for over a decade. Of course the building is still there on Nanjing Road, though (like so much along Nanjing Road) has never recovered its former glory.

Posted: March 23rd, 2017 | No Comments »

The American banker David Rockefeller died this week. Douglas Red, long time Tianjin resident and himself an American banker in China recalled meeting him and discussing the origins of the Rockefeller family’s banking operations in the city….

‘David Rockefeller was a man for all seasons. As a young Chase officer serving in Asia in the 1980’s and 1990’s I was one of many who were honored to escort David as he met senior Chase clients and world leaders throughout the region. He was a graceful man who showed a personal interest in the lives of the countless number of people who knew him (whose names appeared in his famous Rolodex.) My favorite story took place in 1993 when David visited Tianjin, China to help us launch Chase’s first branch opening in the PRC. Speaking proudly to the Chairman Emeritus, I pointed out the old building on Liberation Road (Victoria Road) in which (I claimed) Chase had opened its first branch in Republican China. David was quick to correct me, sharing, “No, Douglas, you are mistaken. My Daddy opened the China Branch of the New York Equitable Banking Corporation here during a family trip to China in the mid 1920’s.”‘

the corner of Victoria Road that marked the divide between the British and French concessions and where the Tientsin (Tianjin) Branch of the New York Equitable Banking Corporation stood

Posted: March 22nd, 2017 | No Comments »

Stefan Huebner’s examination of the development of sport in Asia is a great read (even if, like me, you have no interest in the actual sports themselves)….

The history of regional sporting events in 20th-century Asia yields insights into Western and Asian perspectives on what defines modern Asia, and can be read as a staging of power relations in Asia and between Asia and the West. The Far Eastern Championship Games began in 1913, and were succeeded after the Pacific War by the Asian Games. Missionary groups and colonial administrations viewed sporting success not only as a triumph of physical strength and endurance but also of moral education and social reform. Sporting competitions were to shape a “new Asian man†and later a “new Asian woman†by promoting internationalism, egalitarianism and economic progress, all serving to direct a “rising†Asia toward modernity. Over time, exactly what constituted a “rising†Asia underwent remarkable changes, ranging from the YMCA’s promotion of muscular Christianity, democratization, and the social gospel in the US-colonized Philippines to Iranian visions of recreating the Great Persian Empire.

Based on a vast range of archival materials and spanning 60 years and 3 continents, Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia shows how pan-Asian sporting events helped shape anti-colonial sentiments, Asian nationalisms, and pan-Asian aspirations in places as diverse as Japan and Iran, and across the span of countries lying between them.

Posted: March 21st, 2017 | No Comments »

Monday, 27th March 2017

7:00 pm – 9:00 pm

Family – Ba Jin

Â

The first half of the twentieth century was a period of great turmoil in China. Family, one of the most popular Chinese novels of that time, vividly reflects that turmoil and serves as a basis for understanding what followed. Written in 1931, Family has been compared to Dream of the Red Chamber for its superb portrayal of the family life and society of its time.

Drawn largely from Ba Jin’s own experience, Family is the story of the Kao family compound, consisting of four generations plus servants. It is essentially a picture of the conflict between old China and the new tide rising to destroy it, as manifested in the daily lives of the Kao family, and particularly the three young Kao brothers. Here we see situations that, unique as they are to the time and place of this novel, recall many circumstances of today’s world: the conflict between generations and classes, ill-fated love affairs, students’ political activities, and the struggle for the liberation of women. The complex passions aroused in Family and in the reader are an indication of the universality of human experience. This novel illustrates the effectiveness of fiction as a vehicle for translating the experience of one culture to another very different one.

Li Yaotang (æŽå°§æ£ ; 1904-2005), who also wrote under the pen name of Ba Jin (巴金), is considered to be one of the most important and widely read Chinese writers of the 20th century. Born into a scholarly family in Chengdu, Ba Jin started writing his first works in the late 1920s. An anarchist for most of the Republican period, he formally renounced his anarchist convictions in the 1950s. He was criticized during the Cultural Revolution, during which period his wife died after being denied medical care. He was later rehabilitated in 1977. He suffered from Parkinson’s beginning in the 1980s, which left him unable to speak or walk for the last few years of his life.

RSVP: bookevents@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

ENTRANCE: Members: RMB Non Members: RMB

VENUE: Garden Books; 325 Changle Lu near Shan’anxi South Road é•¿ä¹è·¯325å·, 近陕西å—è·¯ Shanghai

Posted: March 20th, 2017 | No Comments »

I didn’t know this story (despite having walked along Balestier Road many times) – and RE Hale’s The Balestiers is worth a read….

The Balestier family were the first Americans to take up residence in Singapore, where they arrived from Philadelphia in 1834. Although the name Balestier today remains as a road and district, the full story of the family has not been told until now. And what a story it is. Joseph Balestier, aged 46, had received an appointment as United States Consul. He was accompanied by his wife Maria, 48, and their son Revere, 15. On landing, they were shocked to find Singapore closed to American shipping, with no opportunities for earning commissions from the supplying of ships, which Joseph had been banking on for his income. The outlook was grim. But they persevered. A powerful, vivid picture of life emerges, in particular from a newly discovered trove of letters written by Maria to her relatives in America. These letters give us a priceless first-hand view of the family’s daily life, the sometimes absurd customs of Singapore society, the growth of the settlement, the mercantile activity of the port and the colourful characters brought in its wake, and the dangers constantly hanging over their heads – tigers, pirates, malaria, floods. They also reveal, movingly, Maria’s private thoughts – the joys and the heartbreaks. In addition, this volume investigates the Balestiers’ life before they arrived in Singapore, Joseph’s foray into sugarcane plantations in Singapore (at the location which has since come to bear his name), his subsequent travels as US Presidential Envoy, and his life until he died in 1858 – all of which have never before been published in such detail. Combining rigorous historical research with superb narrative skill, author R.E. Hale brings to life the fascinating story of this pioneering family.