Posted: February 19th, 2017 | No Comments »

An interesting new addition to your opium war shelf from Chen Song-chuan…

Merchants of War and Peace challenges conventional arguments that the major driving forces of the First Opium War were the infamous opium smuggling trade, the defense of British national honor, and cultural conflicts between ‘progressive’ Britain and ‘backward’ China. Instead, it argues that the war was started by a group of British merchants in the Chinese port of Canton in the 1830s, known as the ‘Warlike Party’. Living in a period when British knowledge of China was growing rapidly, the Warlike Party came to understand China’s weakness and its members returned to London to lobby for intervention until war broke out in 1839. However, the Warlike Party did not get its way entirely. Another group of British merchants known in Canton as the ‘Pacific Party’ opposed the war. In Britain, the anti-war movement gave the conflict its infamous name, the ‘Opium War’, which has stuck ever since. Using materials housed in the National Archives, UK, the First Historical Archives of China, the National Palace Museum, the British Library, SOAS Library, and Cambridge University Library, this meticulously researched and lucid volume is a new history of the cause of the First Opium War.

Posted: February 18th, 2017 | No Comments »

I expect some day someone will (or perhaps already has) write a Phd on the early fad of poker in China. The fad appears to have been strongest around the mid-1920s. Certainly foreigners in Peking and the treaty ports were all playing poker (even though at the same time there was a mah-jong fad in the USA). This article from 1926 indicates that Wellington Koo (who should need no introduction to China Rhymers) was a poker man – certainly he had a poker face. Carl Crow (as he recounts in his class Four Hundred Millions Customers) made money both ways – he printed a guide to poker in Chinese and a guide to mah-jong in English thereby catching both waves

Posted: February 17th, 2017 | No Comments »

A little post on the Burr Photo Studios of Shanghai. The company started early in the twentieth century at No.2 Broadway (Daming Lu) and moved, later, after World War 1, to No.9 Broadway (as the advert says, opposite the Astor Hotel, now the Pujiang). The studio was run by a Mr J.D. Sullivan with a Mr Menju as the chief photographer, a Miss Canoey and a Miss Dismeyer as the typists (the latter replaced the former at some point in the 1920s) and S.Y. Chu as the company accountant. I believe the ultimate proprietor Mr Menju. Burr’s Chinese hong name was me-lee-fung (美利丰洋行). They did studio portraits and made good money wandering down to the moored up ships nearby and doing crew shots. They also made albums and postcards as well as cartes de visite – of ‘Shanghai, Soo-chow, Hang- chow, etc.’ A postcard produced by Burr of the Bund some time between 1926-1928 (as you can see the construction frame for the Cathay Hotel, started in 1926, completed in 1929) is below with the trademark studio signature in the bottom right corner…

Posted: February 16th, 2017 | No Comments »

The team at Camphor Press in Taiwan have issued several great reprints as e-books (if that makes sense?) – I’ll blog them all eventually, but let’s start with Ezra Pound’s Cathay…which should need no introduction to China Rhymers and all will have a copy on their shelves, but having a copy handily on your mobile device is always nice too….available direct from Camphor here or the ubiquitous rainforest seller here.

Cathay is a collection of classical Chinese poems by Li Bai, interpreted by the American poet Ezra Pound. Though Pound didn’t speak Chinese, he based his translations on notes by Ernest Fenollosa, in the process setting a benchmark for modernist translations. The interpretative nature of Pound’s work broke new ground in the treatment of poetry, and his status as an outsider allowed him a creative space not available to more literal translators. Cathay stands today as a seminal work strongly influential both on the poetry of his day and the succeeding generation.

Posted: February 15th, 2017 | No Comments »

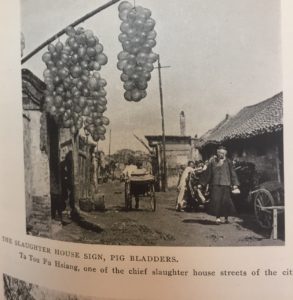

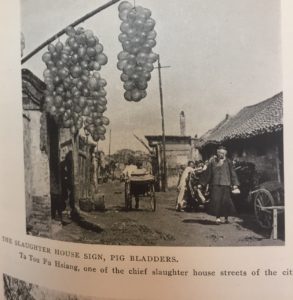

A marvellous old Peking street sign on Ta Tou Fu Hsiang (Ta meaning the big end of the street) for a slaughterhouse – the sign is a couple of dozen inflated pig bladders. One can only imagine the stench but looks interesting….

Posted: February 14th, 2017 | No Comments »

Yesterday I blogged about an old Pekinger Hardy Jowett who went from missionary in the 1890s to an officer with the Chinese Labour Corps in WW1 to a British official in Weihaiwei to an oil executive in Peking….and there was a little story I cam across that was interesting too…from 1930…

The London Guardian reports that Hardy’s son, Christopher, had a bit of an ordeal at the Sino-Soviet border, at Chita, when he was just 18. Here he was, returning from school on England, in October 1930, to Peking. But it seems he lost his passport and, rather unfortunately and no doubt alarmingly for his parents, ended up in a Russian Commie jail without warm clothing or food. It seems he did get moved to a hotel and the whole snafu eventually worked out but among the long list of ‘a funny thing happened to me on the way from school’ stories this must rank pretty nightly….

Posted: February 13th, 2017 | 6 Comments »

As it is the centenary of the formation, recruitment and deployment of the Chinese Labour Corps in WW1 I’ve been putting up the odd post as we move through the year noting highlights of events. If you’re interested just put ‘CLC centenary’ in the search box on this blog and they’ll all come up.

I want to give a quick mention to Hardy Jowett, an old time and long time Pekinger. Hardy Jowett is one of those people who pops up all over the place in China, especially Peking, in the first half of the twentieth century. I have long known him as the man who wrote the introduction to the excellent 1927 guide travel guide Sidelights on Peking Life by Robert W. Swallow. In that introduction Jowett describes himself as an old resident of Peking.

Jowett, from Bradford in Yorkshire, had originally gone to China in 1896 working for S. R. Myers and Co. Ltd., of Colliergate, Bradford. He began mission work in Hankow as a lay worker with the Wesleyan Methodist Society, was ordained and became a missionary.

He sailed with a detachment of the CLC recruits across the Pacific to Canada – when he was nearly 40 (so too old for active service). This means it must have been some time after the dreadful sinking of the Athos (post to come on that) by German submarines – many Chinese drowned in that disaster. The British then stopped using either the Cape of Good Hope or via Suez routes to Europe and opted for the Pacific to Vancouver, train across Canada to Halifax and then a second ship to Europe. This is the route Jowett took. In France he was initially given the rank of Technical Officer and then Second Lieutenant. at the end of the war he transferred to G.H.Q. as a Staff Captain in 1920.

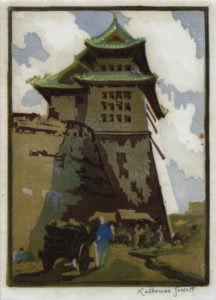

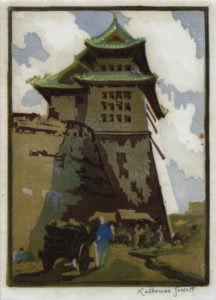

Anyway, he made it through the war, became a colonial official, District Officer and Magistrate, in Weihaiwei for time and then worked for Asiatic Petroleum as their Peking manager till 1933. Along the way he married an artist (Katherine Jowett nee Wheatley – an example of her great block prints below), couple of kids and died, in China, in 1936. His name crops up all the time in research – he was involved in so many things: Rotary Club, Toc H, the China International Famine Relief Commission, the Peiping Institute of Fine Arts, the College of Chinese Studies, the British Chamber of Commerce and the Famine Relief Commission.

Gate of the Rising Sun, Peking – Katherine Jowett

Posted: February 12th, 2017 | 2 Comments »

Echoes of the Manila Galleon c.1584 – 1815

A collection of original antique maps and prints

which ties in nicely to a new Penguin China title:

The Silver Way

China, Spanish America and the birth of globalization

1565 – 1815

by Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales

The show continues until Saturday 11th March 2017

Wattis Fine Art Gallery

2/F 20 Hollywood Road

Central, Hong Kong

Tel +852 2524 5302 E-mail info@wattis.com.hk