Posted: December 9th, 2016 | No Comments »

A chance to see (and buy) some lovely pictures of old Hong Kong…

Wattis Fine Art est. 1988

Specialist Antique & Art Dealers

Hong Kong Illustrated 1843 – 1941

A collection of fine antique prints

(Charles Wirgman – The Illustrated London News – Man Mo Temple, Hollywood Road, Hong Kong 1858)

also featuring a magnificent oil painting of Hong Kong Harbour 1930 by Fred Taylor

The exhibition continues until Friday 23rd December 2016

Wattis Fine Art Gallery

20 Hollywood Road, 2/F, Central, Hong Kong

Gallery open: Monday – Saturday 11am – 6pm

Posted: December 8th, 2016 | 2 Comments »

It is, of course the 75th commemoration of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. That attack meant America and Britain went to war with Japan and obviously had serious and long lasting consequences for China, Shanghai and Shanghailanders. It is also worth remembering that, due to the international date line, the Pearl Harbor attack on the 8th of December in China. this picture has always struck me especially, even though it is not taken in China….

Dec. 15, 1941, Ruth Lee, a hostess at a Chinese restaurant, flies a Chinese flag so she isn’t mistaken for Japanese when she sunbathes on her days off in Miami, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Lee was born in the U.S.

Posted: December 7th, 2016 | 2 Comments »

Some worrying news recently from some friends that visited a “heritage” conference in Shanghai that turned out to be far more about destruction than preservation. Among large number of buildings previously thought protected, but now not, one that stands out in my mind as I always enjoyed passing it and admiring it – the Yichang Road (formerly Ichang Road) Fire Station at 216 Yichang Road in Hongkou, which was formerly the Hongkew Fire Station (and is still a perfectly adequate functioning fire station).

The station was completed in 1932 – replacing an older station that stood there before and had become too small to cope with demand as the suburb of Hongkew expanded and became more densely populated. It is a classic Municipal Council design and opened for business in 1933. There was accommodation for four engines and twelve firemen, recreation rooms, kitchen etc etc. Rewi Alley got his first job in Shanghai at the station and passed his exams for engine driving, pump operation and started Shanghainese lessons while there.

I’m not going to argue about it – if this is bulldozed it will be a major tragedy and an act of vandalism – I’d like to say “unparalleled vandalism” but that wouldn’t be true in Shanghai given the last two decades of destruction.

Posted: December 6th, 2016 | No Comments »

I’ve been spotting opium references in popular culture with interest for a few years now (2015, 2014, 2013 & 2012) – just how opium keeps fascinating us…

What a start to the year with Sherlock on New Year’s Day dipping almost immediately into a Limehouse opium den – not much detail but dope mentioned plenty. Then came ITV’s Jericho, navvies ooop north in pain and needing their laudanum badly. Best perhaps in the first half of the year was the Maharajah’s mistress Sirene (aka Phyllis from Oz) who took a few puffs of opium from her natty little pipe at the Royal Simla Club in series 2 of Indian Summers. Of course series 3 (sadly it seems the final series) of Penny Dreadful went down into Chinatown while series 3 of those Peaky Blinders had them on the “snow” from episode 1 and getting seriously fu*ked up with some naughty White Russians.

I got to it a bit late but season two of the 1870s French bordello drama Maison Close had Rose taking to the pipe as Mosca introduced her to the delights of balanced amounts of liquid cocaine and smoked opium which, if the show is to be believed, heightens all sorts of experiences.

I got to it a bit late but season two of the 1870s French bordello drama Maison Close had Rose taking to the pipe as Mosca introduced her to the delights of balanced amounts of liquid cocaine and smoked opium which, if the show is to be believed, heightens all sorts of experiences.

let’s do the liquid cocaine first then…

let’s do the liquid cocaine first then…

Literary references were a bit scant this year (though that might be my reading of course) but M.J. Lee’s Inspector Danilov series (a third is out in 2017), set in 1920s Shanghai, has the White Russian super sleuth hitting the pipe to assuage the guilt of having lost his family somewhere between Minsk and the Bubbling Well Road – Death in Shanghai and City of Shadows are the first two Danilov books. We did also get a new biography of the great opium eater Thomas de Quincey – Frances Wilson’s Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas de Quincey.

Patrick Hennessey explored Rudyard Kipling’s experiences of opium on hot Lahore summer nights in his BBC documentary Kipling’s Indian Adventure. And finally, of course, the ever reliable Ripper Street (series 5…and, sadly, the final one) had Jedediah Shine staving off his headaches with the opium pipe down in old Chinatown.

Any others do let me know…

Jedediah self-medicates in 1899 Limehouse

Posted: December 5th, 2016 | No Comments »

Homare Endo’s memoir, “Japanese Girl at the Siege of Changchun,†is written from the perspective of her 7-year-old self revealing the horror of one of the Chinese Civil War’s nastiest moments, when between 150,000 and 300,000 civilians starved to death during a five-month siege by People’s Liberation Army at Changchun in 1948.

Over 150,000 innocents died of starvation in Changchun, northeastern China, after the end of WW2 when Mao’s army laid siege during the Chinese Civil War. Japanese girl Homare Endo, then age seven, was trapped in Changchun with her family. After nomadic flight from city to city, Homare eventually returned to Japan and a professional career. This is her eyewitness, at times haunting account of survival at all costs and of unspeakable scenes of barbarity that the Chinese government today will not acknowledge.

Homare Endo was born in China in 1941 and is director of the Center of International Relations at Tokyo University and Graduate School of Social Welfare.

Posted: December 4th, 2016 | No Comments »

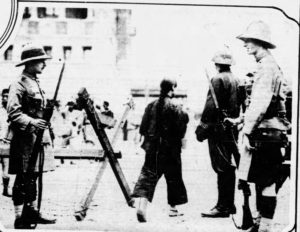

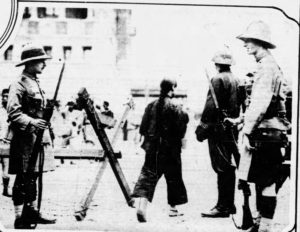

One canny photographer got a great shot that ran in many, many newspapers in the early 1920s – Shanghai – with a woman wearing trousers and two men, Scottish soldiers, wearing kilts. This picture ran in newspapers round the world in November 1924.

Now I’m rubbish at uniforms, regiments and all that so perhaps someone more knowledgeable can tell me if these gentleman are i) a Scottish regiment stationed in Shanghai at that time or b) members of the Scottish Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps??

Posted: December 3rd, 2016 | No Comments »

“Devils on the Doorstep(鬼åæ¥äº†)”a 2000 black comedy directed by Jiang Wen, will be preceded by remarks by Matthew Hu Xinyu. You may know that the movie, set in the waning days of WWII, sparked heated discussion because it underscores common human traits of both Japanese and Chinese. But did you know its most memorable scenes were filmed not far from Beijing in Hebei province? Before the film, Matthew Hu Xinyu, one of Beijing’s top cultural-preservation experts, will identify important examples of ancient Chinese architecture shown in the film.

WHAT: “Devils on the Doorstep” film showing, preceded by remarks by Matthew Hu Xinyu

WHEN: Saturday, Dec. 3 from 6:30 to 9:00 PM

WHERE: The Courtyard Institute, #28 Zhonglao Hutong, Dongcheng District www.courtyardinstitute.com

COST: 30 RMB for RASBJ members; 50 RMB for non-members

RSVP: please email events@rasbj.org and write “Devils” in the subject header

PLEASE NOTE: The black-and-white film, which is 139 minutes long, will be shown in Chinese with English subtitles

Posted: December 2nd, 2016 | No Comments »

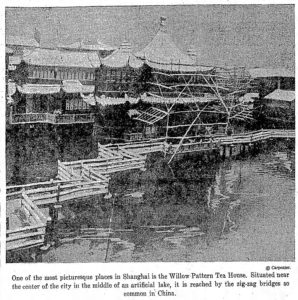

aaahhh lovely – no crowds, no tour groups with yellow baseball caps, no Starbucks, no tour guides with megaphones, but with snow in 1924….appears to be a little bit of restoration going on with some bamboo scaffolding up…