Posted: September 3rd, 2016 | No Comments »

The Rice Theory of Chinese Culture

Why do northern Chinese behave differently from those in the South?

You’re invited to a fascinating talk on China’s two psychological cultures by Thomas Talhelm, who found large differences between people in northern and southern China—and that these differences were correlated with the amount of rice historically grown in different provinces. In a recent study, published on the cover of Science, psychologist Talhelm argues that rice farming’s intensive labor requirements and irrigation networks encouraged labor exchanges and tight, reciprocal relationships. In contrast, wheat’s lower labor and water requirements lead to the north’s more independent and free-wheeling culture. For more insights into Talhelm’s research see the Economist, National Geographic, and NPR. Talhelm will also explain why Beijingers are likely to push chairs around more when they visit Starbucks.

WHAT: “The Rice Theory of Culture in China”, a talk by Thomas Talhelm

WHEN: Tuesday, Sept. 6 from 8:00 – 9:30 PM

WHERE: Â The Bookworm, Courtyard 4 Nansanlitun Lu, Chaoyang

COST: RMB 65 for members of RASBJ or Bookworm, RMB 75 for non-members

RSVP: email events@rasbj.org and put “Rice Theory” in the header

YOOPAY LINK: https://yoopay.cn/event/80703525

ABOUT THE SPEAKER:

Thomas is a 2012-2013 Fulbright scholar to China and assistant professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago. He researches cross-cultural differences and north-south cultural differences in China. He has lived in China (both north and south) for four years doing research, as a Princeton in Asia fellow, and as a freelance journalist. He is also founder of Smart Air, which promotes low-cost DIY air filters as an alternative to the high-priced air purifier market.

Posted: September 2nd, 2016 | No Comments »

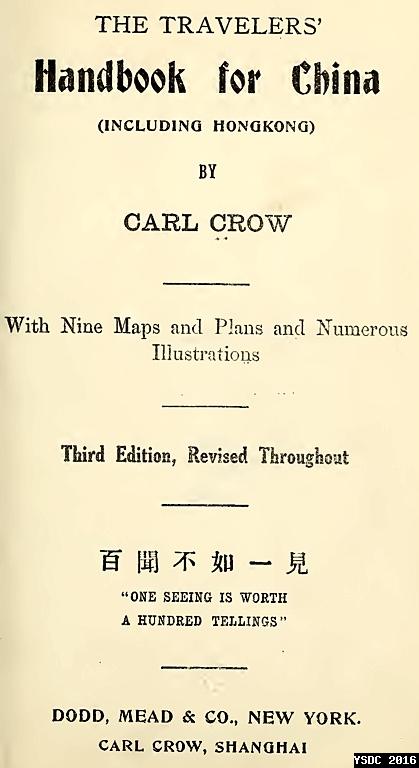

The G20 are in Hangzhou, the Chi-Comms have not gone nuts as ever – rooftop snipers, no backpackers, fines for spitting, residents told to vamoose, rapid tart ups of streets and buildings occurred. Worth remembering perhaps what Carl Crow thought of Hangchow (Hangzhou, if you must) from his 1921 edition of the Travelers’ Handbook for China (available here in a great e-book edition with an intro my yours truly)…..

“This city with a population of 750,000 is located on the Shanghai–Hangchow–Ningpo Railway and also on the Ch’ien T’ang River, no miles southwest of Shanghai. The towing charge for a houseboat from Shanghai to the Hangchow Settlement is from $10 to $15. From the Settlement it is necessary to go by train to the city station and thence to a hotel. Several Chinese hotels serve foreign style meals but the New Hotel on the West Lake is especially recommended.

Among the renowned cities of China, Hangchow, the capital of Chekiang Province, holds a most important place. Few other cities have played such an important part in the dramatic history of the country and few others are as picturesque, though most of its ancient glories have disappeared and the city is only a fraction of the size it was in its prime. In point of historical interest Hangchow is second only to Peking, while for the beauty of its surroundings it is even now second to no other city in China.

Marco Polo came to Hangchow, following the Mongol invasion, and his description of the city shows that much of its ancient grandeur had remained and some of it had been restored. Even then, in art, literature and commerce it was the Queen City of the Orient. It was the center of Oriental fashions and gaiety. Hither came merchants, travelers, missionaries and adventurers to view the place and enjoy material delights. The account that Marco Polo gives reads almost like the stories of ancient Rome in regard to the sensual indulgences of the people.

In A.D. 1860 and again in 1862 the T’ai P’ing or Long Haired Rebels came to Hangchow and in a few months reduced nine-tenths of the city to ashes and, utter ruin. It is stated that four fifths of the inhabitants were massacred, or committed suicide, while the remainder were driven from the city. The canals were-so full of the bodies of those who had committed suicide that those later wishing to end their existence could not find sufficient water in which to drown themselves. Even the West Lake was so filled with dead bodies that one could walk out on it for a distance of a half li on them.

Since the establishment of the Republic Hangchow has made notable civic progress. The Tartar City section is one of the finest of its kind in all China. Not even in Shanghai are to be found such broad fine streets. With the building of the railway Hangchow has again become the objective of thousands of travelers and it would seem as if the new hotels could not be built fast enough to accommodate all who come. The city abounds in pleasant little gardens and parks and altogether has the air of the pleasure resort that it is.

A variety of industries are carried on in Hangchow. Among the ancient industries which have survived is the manufacture of “joss paper,†made from paper and tin foil. Even this industry has become modernized for in Hangchow they make imitations of Mexican dollars rather than the former clumsy representations of the silver sycee.

The most famous fan shop as well as the most famous, drug shop in China are to be found in this city. One wall of the fan shop is covered with certificates of awards received at foreign expositions. The drug shop is uncontaminated by modern ideas and dispenses nothing but remedies approved by the Chinese pharmacopeia. Attached to the establishment is a large number of deer cages where deer are kept. Any deer that are presented for sale are bought at once, so as to encourage the hunters. The cost per deer is from two to four hundred dollars. The shop claims that everything is used but the horns, a statement that may be skilful camouflage rather than the exact truth.

The Needle Pagoda or “Prince Shu’s Protecting Pagoda†with the other two famous pagodas of Hangchow mentioned below date back to the great building period of the Wu-Yueh Kings, approximately 950 years ago.

On the opposite or southern side of the Lake is the Thunder Peak Pagoda, also called the White Snake Pagoda. This pagoda was built by a concubine of one of the Wu-Yueh Kings, also about 950 years ago. It was originally planned to be seven stories high but for geomantic reasons it was reduced to five. Many of the pagodas in China are built in order to affect the fêng shui in other words to control weather conditions. They are often built over the bones of some Buddhist priest who was regarded as a saint. Very often there are attached to them a monastery or temple and the pagoda itself often contains many Buddhist images which are worshipped by the pilgrims who come from the countryside.

The Six Harmonies Pagoda is located on the Ch’ien T’ang River about a mile and a half from the terminal station Zahkou. It is one of the largest Pagodas in all China.

The principal points of interest on the West lake are the Imperial Island, called Ku-Shan (Solitary Hill) by the Chinese, also the lake dykes or causeways. About A.D. 1130 and later the lake and Imperial Island were made famous by the residence of the Southern Sung Emperors. In addition to visiting the various memorial halls on the island one ought to visit the public park, originally the site of one of the palaces of Emperor Ch’ien Lung. From the upper part of the park one can get a fine view of the lake.

If one has the time it is worth while to visit the MohamÂmedan Mosque built in the T’ang Dynasty about A.D. 630. This Mosque is one of the ancient landmarks of Hangchow. If possible it would also repay the tourist to visit the City Hill and from there get a view of the city, the bay and the Ch’ien T’ang River, also the lake and the surrounding hills. It is a view of picturesque beauty uncommon in China.”

Posted: September 1st, 2016 | 7 Comments »

The wines and spirits distributor Caldbeck Macgregor is intrinsically linked with Shanghai – you can still their old HQ down on Foochow Road (Fuzhou Road) and I blogged about it way back when (here). Caldbeck Macgregor was early in Shanghai – establishing in 1864 (as George Smith & Co.) and serving thirsty taipans right from the early years of the treaty port. The company assumed the name Caldbeck Macgregor in 1883. However, they soon spread out across South East Asia and today are most commonly associated with Malaysia. Still, here, from 1928, some Caldbeck Macgregor ads for their Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur outposts (though still a company incorporated in Shanghai)…

Posted: August 31st, 2016 | No Comments »

Seriously, you can’t ever really get enough of the Flying Tigers and you know it!! And so a new biography from Robert Coram of Robert Lee Scott Jr., Double Ace.

Robert Lee Scott was larger than life. A decorated Eagle Scout who barely graduated from high school, the young man from Macon, Georgia, with an oversize personality used dogged determination to achieve his childhood dream of becoming a famed fighter pilot. In Double Ace, veteran biographer Robert Coram, himself a Georgia man, provides readers with an unprecedented look at the defining characteristics that made “Scotty” a uniquely American hero.

First capturing national attention during World War II, Scott, a West Point graduate, flew missions in China alongside the legendary “Flying Tigers,” where his reckless courage and victories against the enemy made headlines. Upon returning home, Scott’s memoir, brashly titled God is My Co-Pilot, became an instant bestseller, a successful film, and one of the most important books of its time. Later in life, as a retired military general, Scott continued to add to his list of accomplishments. He traveled the entire length of China’s Great Wall and helped found Georgia’s Museum of Aviation, which still welcomes 400,000 annual visitors.

Yet Scott’s life was not without difficulty. His single-minded pursuit of greatness was offset by debilitating bouts of depression, and his brashness placed him at odds with superior officers, wreaking havoc on his career. What wealth he gained he squandered, and his numerous public affairs destroyed his relationships with his wife and child.

Backed by meticulous research, Double Ace brings Scott’s uniquely American character to life and captures his fascinating exploits as a national hero alongside his frustrating foibles.

Posted: August 26th, 2016 | 1 Comment »

I’ve worked for some time trying to find traces of the old Roma community of Shanghai. The Roma of Shanghai in the first half of the twentieth century are a significantly under-researched community, not falling easily into any official classifications and also suffering the prejudices and discrimination common to the Roma in our own time too. However, there was a thriving Roma community in old Shanghai that was engaged in business and the entertainment industry and while we may not have as much information on them as we do on other groups of Shanghailanders they are no less important in understanding the total ethnic make up of the city, its International Settlement and French Concession.

Anyway, if the history of the Roma in Shanghai interest you then this small publication (for an equally small price) may be of interest to you….It’s available on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Posted: August 25th, 2016 | No Comments »

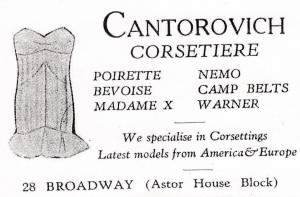

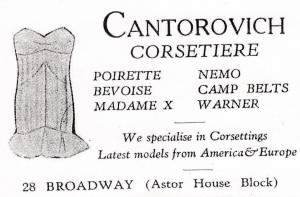

My first post on old Shanghai lingerie retailers – Horace Beeson – was in the Settlement, south of Soochow Creek. But what if you were in Hongkew and couldn’t be bothered crossing south? then it’s got to be Cantorovich for you down on Broadway (Daming Road), close by the Astor House Hotel (Pujiang Hotel these days). Cantorovich certainly stocked plenty of imported brands – Poirette, Warner etc – and styled themselves a “corsetiere”. the Chinese name of the store was Yue Luen (豫纶洋行). It was run by a certain I. Cantorovich with his wife (who was called Mary) and had been established in the late 19 teens or early 1920s as a general milliners, drapers and outfitters (this advert is from 1930) at No.11 Broadway. The Cantorovich’s were apparently originally from Moscow and were obviously White Russian refugees in Shanghai.

NB: In the 1930s it seems the Canotorvich’s split up. He continued to run the store but his wife, Mary, apparently became quite a ‘woman-about-town’, involved in various shady deals, being squired by various western and Chinese businessmen around, claiming to be a Princess (hardly original!!) and generally being rather louche. Her greatest moment of notoriety came when she was involved with the corrupt Canadian businessman CC Julian who’d been involved in various oil stock related scams in California. She claimed to be Julian’s lover, claimed that she was representing interests who would buy his tell-all autobiography from him. When Julian committed suicide in Shanghai’s Astor House hotel in 1934 she turned up at the hospital too. Quite a notorious ride from selling underwear down by the Soochow Creek (PS: I blogged on the CC Julian scandal here)

Posted: August 24th, 2016 | No Comments »

I greatly enjoyed the new translation of White Russian writer Teffi’s Memories, from the excellent Pushkin Press. Though Teffi (below) eventually settled in Paris and never visited China she does mention some fellow writers, artists and journalists who escaped communism by settling in China. Some of these we know well – the singer and cabaret artist Alexander Vertinsky who ran a Shanghai nightclub and the artist Alexandre Jacovleff for instance.

Additionally, (and here’s where China Rhyming readers may be able to help) Teffi also mentions Fyodor Blagov, who was an editor with the Russian Word newspaper in Moscow before the Bolshevik Revolution. A footnote to Teffi’s mention of Blagov (not written by Teffi herself but by the published indicates that Blagov (1886-1934) worked for White Russian newspapers in Harbin and Shanghai up until his death.

However, I know of no references to Blagov’s time in China, either Harbin or Shanghai. I’ve consulted a few specialists on the Russian community in China who don’t know of him either. At least not in relation to Shanghai. Anybody out there know anything?