Posted: August 23rd, 2016 | No Comments »

I know you’ve always wondered just where to get a fine item of lingerie in Shanghai? Beeson’s was certainly one possible solution. They were down on Nanyang Road (interestingly, one of the few roads that kept its pre-1949 name) behind the Bubbling Well Road. Fittingly there are still a few small clothing stores and tailoring businesses along that street as well as some bars. Beeson’s was a ground floor retail unit with apartments above. The company was run by Horace Beeson, an American (from Media, the county seat of Delaware County, Pennsylvania) and started, I think, in the mid-1920s. Horace had previously worked in the early 1920s for Gaston, Williams and Wigmore in Shanghai – a Canadian company that sold cars, motorcycles and even ship, I think, around the world. He’d also worked for Elbrook’s, American importers, engineers and exporters based on the Kiangse Road (Kiangxi Road). Obviously at some point lingerie (understandably) appealed a little more to Horace than piston engines.

This advert is from 1930 bit I think the company had some problems and shut down around 1933 being taken over by the Sheppard Import Company.

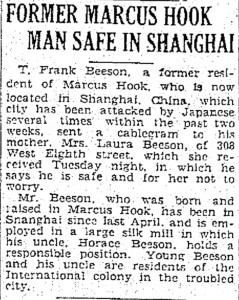

The Beeson family had quite a relationship with Shanghai. Horace briefly involved his nephew Price Beeson in the business (see the article on him below) and his brother (and obviously also a nephew of Horace’s), T. Frank Beeson, who worked for the silk mill that supplied Beeson’s. Price and T. Frank seem to have left Shanghai around the time of the troubles with Japan in 1932.

Posted: August 21st, 2016 | No Comments »

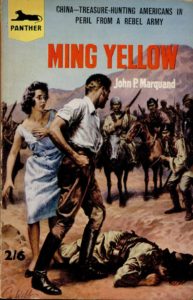

I’m not sure I could really recommend John P. Marquand’s Ming Yellow (1935), but it is an interesting and mostly forgotten China book. The blurb reads:

WHO was the ruler in this terrible kingdom of death?

Was it the General, a laughing giant who could break a dancing girl’s body in a fleeting moment of anger? Or was it the bandit, a mysterious wraith who could joke in the echo of her screams? Or was it the guide, who juggled four lives while he walked a fragile tightrope of deception?

For the four Americans, helpless strangers in a forbidden land, the answer could be the key to freedom and wealth – or a sentence of death!

You get the idea – American hardboiled in China

We’re in Warlord infested China on the trial of some rare and valuable pottery. Americans are generally good; Chinese (even American-educated ones) generally bad.

However, Ming Yellow is perhaps worth mentioning for two reasons. Firstly, John P Marquand (below), now best remembered as the creator of the Mr Moto series. Ming Yellow just slightly pre-dates the first Mr Moto books indicating Marquand was looking for both a good idea and a money spinner. Moto was to be that. Though generally derided (as well as the movies with Peter Lorre) I would suggest that the last in the series – Stopover: Tokyo (written much later than the others in 1957) is a taught and well crafted thriller that offers distinctly more than the earlier books.

However, some descriptive elements of China ring true in Ming Yellow. Marquand had visited China in 1934 to research “colour” and locations for the book and his Mr Moto series (I’ll blog separately on Marquand’s China trip).

Secondly, the edition of Ming Yellow below got a cover from the pen of Reginald Heade, undoubtedly Britain’s best pulp fiction cover artist. This cover was actually surprisingly subtle for Heade! His work was usually far more raunchy (see a selection here).

Posted: August 20th, 2016 | No Comments »

A slight diversion. I’m sure some readers of this blog think me permanently trapped in the past. This is true, largely, though I do attempt to monitor the state of things currently too. Mostly I do this through editing and commissioning a series of books for Zed Books in London on contemporary Asian issues – Asian Arguments. If I do say so myself Asian Arguments has built up over the last six or seven years or so into a nice list of a couple of titles a year covering the region fairly well and with a mix of authors including journalists, academics, NGO workers and activists. There’s been a blend of veteran writers as well as first timers and there’s more to come soon on Burma, Xinjiang, Thailand and elsewhere in Asia.

But this month we have the latest in the series – China and the New Maoists (here on Amazon.co.uk and , from Kerry Brown and Simone van Nieuwenhuizen….

Forty years after his death, Mao remains a totemic, if divisive, figure in contemporary China. Though many continue to revere him and he retains an immense symbolic importance within China’s national mythology, the rise of a capitalist economy has seen the ruling class become increasingly ambivalent towards him. And while he continues to be a highly visible and contentious presence in Chinese public life, Mao’s enduring influence has been little understood in the West. In China and the New Maoists, Kerry Brown and Simone van Nieuwenhuizen looks at the increasingly vocal elements who claim to be the true ideological heirs to Mao, ranging from academics to cyberactivists, as well as at the state’s efforts to draw on Mao’s image as a source of legitimacy. A fascinating portrait of a country undergoing dramatic upheavals while still struggling to come to terms with its past.

Posted: August 19th, 2016 | No Comments »

IThe old Fuhsingkang Film Production Studio is in Taipei. It is not used anymore and, though the last film made there was 1995, its heyday was really the 1950s and 1960s. As with everything about the early days of the Republic of China in Taiwan it was under the control of the military – specifically the Ministry of Defense Political Warfare Division. It is also the case that the history of the Fuhsingkang Film Production Studio is intertwined with that of Shanghai.

After 1949 of course some of the stars, directors, screenwriters and technicians associated with the Shanghai cinema industry remained in mainland China and took their chances with the new communist leadership (invariably that did not end well!). Many went to Hong Kong and that story is well known I think. Only an estimated 5% of the Shanghai film industry went with the KMT to Taiwan and (according to James Udden’s informative No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien) most of those were people who had worked on educational and propaganda films. Udden says this meant Taiwan got a lot of technical equipment and fair amount of expertise but rather less creative talent. However, some classics were produced – Storm Over the Yangtze River (1969 – pictured below), The Story of Tin-Ying (1970).

Now the Taipei authorities are about to decide whether to bulldoze the old site and build a new film studios (though some might say that Taipei’s Beitou District is a little too crowded for a major studio?) or turn the existing buildings into a museum of Taiwanese cinema and a film school. I rather hope the latter personally.

Posted: August 18th, 2016 | No Comments »

Talking about Julian Maclaren-Ross’s Memoirs of the Forties yesterday (in relation to Dylan Thomas and the Free Japan movement) I also noted that Maclaren-Ross makes mention of dining at L’Orient in St. Giles. I happened to blog about the old L’Orient Restaurant on London’s St. Giles High Street last year (here). It was of interest to me as once being a stalwart of the capital’s interwar and post-war Chinese restaurant scene (I have a long article on the city’s 1930s and wartime Chinese restaurant scene coming in the September edition of The Cleaver Quarterly magazine, by the way). The establishment is sadly long gone, as is the majority of St. Giles High Street, under what is now the Centre Point tower block. Here’s the only picture I have of the place…and it’s just a street scene with the sign…

Anyway, Maclaren-Ross remembers dining there during the war, around 1943, with the Sri Lankan poet (famous at the time) Tambimuttu. He recalls that it stayed open late – they dined there after a pub crawl of Fitzrovia. I believe that due to the wartime restrictions and shortages of meat this was the time, Maclaren-Ross also refers to, when they dined on L’Orient’s horsemeat curry!

Maclaren-Ross

Maclaren-Ross

Tambimuttu

Posted: August 17th, 2016 | No Comments »

Re-reading Julian Maclaren-Ross’s Memoirs of the Forties it jogged my memory that he mentions the Free Japanese movement in London. I know next to nothing about the Free Japanese movement in World War Two and so can echo the words of Dylan Thomas (who Maclaren-Ross was working with at the time) – “he had heard of Free French, Free Poles, Free Dutch, Free Italians and if not actually Free Germans at any rate Free German-speaking people, but never, no never Free Japanese.” Me neither (though I could add the Shanghai chapter of the Free Austrians to the list, about who I blogged here). So, a bit of a hunt….

So here’s how they crop up:

- It’s 1943 and Maclaren-Ross has wangled a job out of the forces and with Strand Films as a scriptwriter on propaganda productions;

- Working at Strand with him is the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas;

- Strand was based at No.1 Golden Square in Soho (picture of that building, now Bauer Media, as it is today below) – in the same building Maclaren-Ross and Thomas notice a sign for “Free-Japanese Lampshades”;

- Certainly there had been Japanese lampshade manufacturers in London, not that far away from Golden Square, in London’s pre-war “Little Tokyo” of Denmark Street (see Keiko Itoh’s The Japanese Community in Pre-War Britain for more on that community, now mostly forgotten) but they all shut down by 1941.

- According to Itoh, above, Japanese were all either repatriated or interned by 1943.

I’m afraid I know little about the Free Japanese beyond a Wikipedia entry that deals with Japanese Communist Party members who were in Yenan with the Chinese communists during the war. However, no references (including in Itoh’s book) to London and Free Japanese, except Messrs Maclaren-Ross and Thomas.

Anyone know anything?

Posted: August 16th, 2016 | No Comments »

Following on from yesterday’s post….(thanks to Doug Clarke of Gunboat Justice for a few more Paul’s Beauty Parolurs ads)

Posted: August 15th, 2016 | No Comments »

What can I tell you about Paul’s Beauty Parlours? Not much I’m afraid apart from what’s in the advert. Prestige addresses on Nanking and Bubbling Well Road (Nanjing and Nanjing West Roads). The claim to be oldest might be disputed (this advert from the early 1930s). I think (and if anyone knows different do let me know) the chain was owned by a White Russian in Shanghai (Paul was, I think, the surname and not the forename). There was competition – that stretch of Nanking Road was home to a host of beauticians from the mid-1920s. The Nanking Road branch was a shared premises with other businesses including the Josefo Photo Studios (who I must get round to posting about one day).