Posted: December 15th, 2015 | No Comments »

1932 – Japan invaded Manchuria and the Chinese portions of Shanghai. The media decided that this was one of the “high spots” of the year along with: the jailing of Al Capone, the assassination of the French President; the murder of an army wife in Honolulu; the Lindbergh baby kidnapping; Emilia Earhart solo-ing the Atlantic; FDR winning the Democratic nomination; riots with the Bonus Marchers, Gandhi on hunger strike and the Mayor of New York indicted on corruption charges…

Posted: December 14th, 2015 | No Comments »

From Murdoch to Kuok to Ma…but back in the day the SCMP was the proud possession of an American dentist….

After having lampooned its launch in 1903, the Hongkong Telegraph was merged into the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong (where newspapers always appeared to be far more businesslike than in the treaty ports) when Jardine Matheson’s wealthy Eurasian comprador Robert Hotung sold a controlling interest in the Telegraph to Dr. Joseph Whittlesey Noble in 1916. Noble, from Pennsylvania, was Hong Kong’s second registered dentist who had been in practice in the colony since 1887, meaning that the Post held the dubious distinction of being the only newspaper in the world to be owned by a dentist.

Â

Posted: December 13th, 2015 | 1 Comment »

The Chicago Tribune has a great series of photographs of the city’s Chinese community from the 1930s to the 1970s. They include the community’s support for China in World War Two, celebrity visits, criminals, school etc etc… well worth a look – click here.

Below some Chinese gangsters pulled in in the 1930s Hip Song Tong wars….

Posted: December 12th, 2015 | No Comments »

As the South China Morning Post is now probably about to exit the market as a serious independent newspaper (mainland firm Alibaba having agreed on Friday to buy the media assets of the SCMP Group) it might be worth recalling its rather rocky start back in 1903…

From my book Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao….

The Arrival of the Post

At the same time, the press in Hong Kong was growing but it wasn’t exactly a boom time: by the early 1920s the combined circulation of English-language papers in the colony was barely 5,000 daily. The South China Morning Post was founded in 1903 and published its first edition in November, declaring itself the colony’s first “modern newspaperâ€. The press was also becoming a force for social progress in Hong Kong by making suggestions that influential citizens of the colony adopted. Hong Kong’s China Mail first proposed combining the existing medical and technical colleges to form a university for the colony, an idea the Parsi businessman Hormusjee Mody took up at the insistence of prominent businessman Paul Chater and bequeathed its major building to the new Hong Kong University. Unfortunately, Mody died before the university building was completed.

The South China Morning Post, or the Post as it quickly became commonly known by everyone, was to outlive its major competitors, the Hongkong Telegraph, the Hongkong Daily Press and the China Mail to become regarded as one of the best papers in the Far East. The Post’s launch wasn’t popular with the competition. As the Hongkong Telegraph noted, “Hongkong’s troubles are to be increased by the addition of a new daily newspaper with the voluminous title of The Morning Post of South China … We sympathise deeply with Hongkong. It will soon be as bad as Shanghai in this respectâ€. The paper’s founders —Arthur Cunningham who had covered the Sino-Japanese War for the Hongkong Daily Press in 1894 and the Australian-born Chinese political activist Tse Tsan-tai — begged to differ. The Post marked somewhat of a sea change in Hong Kong, declaring in its opening editorial on 6 November 1903:

The modern newspaper has taken the place of the old-time ambassador. The cynic has said the ambassador is sent abroad to lie for the good of his country. The newspaper is sent abroad to tell the truth for the good of humanity. Whereas the ambassador, by means of weary months of negotiation, may make or prevent a war; a newspaper by means of a few trenchant articles, so be that they have truth behind them, will rouse a public to resent aggression, so to reform abuses, to mould the policy of governments. Such is the power of the modern newspaper.

Tse Tsan-tai, who had been baptised James See, was a particularly transnational character for the times. Born in Grafton, Australia, to a family of Chinese merchants, he moved to Hong Kong in 1887 to study at Queen’s College and was one of the founders of the Literary Society for the Promotion of Benevolence (Furen Wenshe). In 1895 Tse and his colleagues aligned themselves with Sun Yat-sen’s Hing Chung Hui (Society for the Restoration of China), though Tse and Sun soon fell out. Tse recalled Sun as “… a rash and reckless fellow. He would risk his life to make a name for himself. Sun proposes things that are subject to condemnation — he thinks he is able to do anything — no obstructions — ‘all paper!’â€. Though history has crowded out Sun’s detractors

in the early days before he rose to power, there are many and his nickname was the “windbagâ€. Later, in the 1930s, a heated debate would arise in Australia when some prominent overseas Chinese campaigned to have Tse recognised as the true father of the Chinese Republic, thereby arguing for the demotion of Sun.

Tse pushed hard for social change in Hong Kong, arguing that the Chinese community should elect the Chinese representatives on the Legislative Council rather than having them nominated by the governor, as well as inventing an advanced steering system for airships. He campaigned against superstition, feng shui, footbinding and opium smoking, while promoting religious tolerance, railways and mining, and calling for the protection of China’s heritage. He had corresponded with Morrison since the 1890s, was friendly with the Hongkong Telegraph editor Chesney Duncan and also knew Cunningham well when he was the editor of the Hongkong Daily Press. In 1901 Tse worked briefly for the China Daily, the newspaper of the Society for the Restoration of China. As well as being a prolific journalist and newspaper proprietor, Tse also authored about half a dozen books on subjects ranging from ancient Turkestan to solving unemployment, to why typhoons occur. He was nothing if not a multi-tasker.

Tse and Cunningham appointed Douglas Story as the paper’s first editor. Their founding aim was to present the viewpoint of both the British colonial regime and the business community and promote the cause of republicanism in China. This was a tricky project and wasn’t an easy balancing act. Story only lasted a year, claiming that he didn’t like Hong Kong because people took too many holidays and played too much sport. However, he was a staunch supporter of self-government for Hong Kong and considered the governor’s post unnecessary. Transition from a crown colony to a self-governing colony would allow Hong Kong to flourish and also allow for greater Chinese involvement in affairs. Although in a seeming contradiction to opposing crown colony status, he also staunchly defended the rights of British trade in China and spoke out against what he saw as American encroachment on British business interests — Washington’s “Open Door†policy.

Despite all this, the Post’s early survival was far from sure. Within a few years at the turn of the century several new papers, as well as the Post, appeared in Hong Kong along with the nearby Canton Daily News, which sought to compete with the rather larger and well-established Canton Chronicle. It seemed that, although the market was already crowded, investors thought newspapers were a potentially profitable investment, but this wasn’t initially the case. Despite the rather vague claims from the backers of the Post that investments in the paper would earn returns of anywhere between 12% and 200% a year when they issued $150,000 worth of shares at $25 each, three years later shareholders had received no dividends and the shares were valued at just $18. The Hongkong Telegraph gloated over the Post’s initial financial woes, noting both the difficulty of the English- language newspaper business in Asia and remembering the early days in the Canton factories: “Conditions in the Far East have changed since the time when anybody could come along with a hand press and start a paper …â€. Despite this gloomy prognosis, the Post persisted and ultimately outlasted all the competition.

The Post survived its early traumas. Various acting editors ran the paper until 1910 when Angus Hamilton was appointed, but he lasted only a few months. Hamilton, an English correspondent of aristocratic background, had started out working on the New York Evening Sun which sent him to Korea. He then found work as a war correspondent for the Times, covering the defence of Mafeking alongside Baden Powell before moving to the Pall Mall Gazette where he covered the Siege of the Legations, the wars in Somaliland and those between the Balkans and Macedonia at the turn of the century. Then, job-hopping again, the Manchester Guardian hired him to report from the frontlines during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, and he also visited Afghanistan before finally being hired by the Post. Though an immensely talented man, he was also troubled and restless. He lingered in Hong Kong for only a short while before heading to India and then becoming a reporter for Britain’s Central News Agency in the Balkans where he was twice captured by the Bulgarians and severely tortured as a Turkish spy. He travelled to America to give a series of lectures on his experiences around the world, only to discover he was a poor speaker, nervous and attracting small audiences. Considering himself a failure, in dire financial straits, suffering from ill-health courtesy of his Bulgarian torturers and unsure of the future, he cut his throat in a New York hotel room.

As the immediate terror of the Boxers receded, China found itself faced with new challenges — a continually ossifying Qing court that had caused the humiliation of China, as a result of which the country had to accept a greater foreign presence on Chinese soil. At the same time, other rising powers chose China as a battlefield for their grievances.

Posted: December 11th, 2015 | No Comments »

Seeing images from Beijing this week of the disgusting air quality did make me think that, pollution aside, Peking was always a fairly foggy city. It certainly was in 1976 when Dick Nixon, by then a former president, flew in to a “pea-souper” (other papers described it as a “cold mist”) at Peking Airport for the fourth anniversary of his historic 1972 rapprochement visit. They arrived late at night so I’m not sure a picture survives of the actual fog.

Qiao Guanhua meets Dick and Pat at Peking Airport. Qiao was Foreign Minister but associated with the Gang of Four. When Mao died a few months later in September he was sacked, sidelined and never regained any significant political authority. The woman with Qiao is presumably Zhang Hanzhi, his second wife and an English interpreter for Mao himself at times. She had been Nixon’s translator in ’72. Her divorce from her first husband had been a “Red Scandal” in 1973 and Qiao was 22 years her senior.

Qiao Guanhua meets Dick and Pat at Peking Airport. Qiao was Foreign Minister but associated with the Gang of Four. When Mao died a few months later in September he was sacked, sidelined and never regained any significant political authority. The woman with Qiao is presumably Zhang Hanzhi, his second wife and an English interpreter for Mao himself at times. She had been Nixon’s translator in ’72. Her divorce from her first husband had been a “Red Scandal” in 1973 and Qiao was 22 years her senior.

Posted: December 11th, 2015 | No Comments »

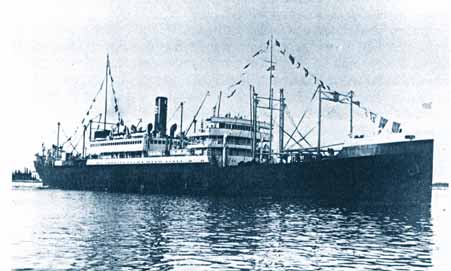

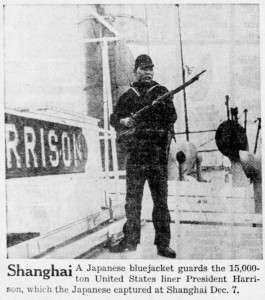

Actually this is December 8th in Shanghai – though it was December 7th in Pearl Harbor. After the Japanese attack on America began it was about 4am when Shanghai heard. The Japanese moved swiftly and here is the President Harrison under Japanese Bluejacket Marine guard this week in 1941…

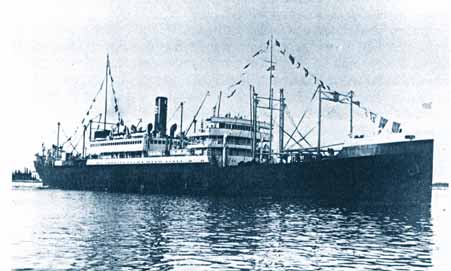

The story of the Harrison is compelling and told in David and Gretchen Grover’s Captives of Shanghai. The President Harrison was formerly the Wolverine State American Passenger Vessel later renamed Harrison in 1922 operated for the U.S. Shipping Board in U.S. Pacific coast/East coast of South America trade. The ship was transferred to Dollar Steamship Lines in 1923 and inaugurated the Dollar Line’s first Round-the-World service in 1924. In December 1941 the Harrison was chartered by the US government to evacuate the last of the 4th Marines and Navy personnel from Shanghai. While on her way to Chinwangtao (Qinhuangdao now) to embark a few more stranded Marines she was captured by the Japanese Navy off Shanghai on the 8th December 1941 close to the Saddle and Shaweishan Islands (now the Ma’an Liedao and Zhoushan Dao respectively) at the mouth of the Yangtze.

The Harrison was later renamed the Kakko Maru and flagged as Japanese. On the 12th September 1944 she was sunk by a torpedo from the American submarine USS Pampanito off Hainan Island heading for Formosa. Sadly she was carrying Australian and British prisoners of war, who had survived the building of the Death Railway.

Posted: December 10th, 2015 | No Comments »

A post on the Los Angeles Review of Books China blogs site of year end book reviews…it was a tricky one for China books this year with no stand out original offerings (in my humble opinion)…still, it’s that time of year so recommendations must be made! I opted for photography this year as that’s a format that seems to be offering more originality at the moment. I’d add that Katya Knyazeva’s Shanghai Old Town book looks fantastic but I haven’t actually sat down and read it yet so couldn’t include it.

What I did find engrossing this year were a number of books that approached the history of cities from different perspectives, all of which could provide templates for good China history books too I think, so I’ll note them….

Reading Catriona Kelly’s St Petersburg: Shadows of the Past I couldn’t help thinking that Shanghai or Beijing deserve similar books that really get under the skin of the city. Nobody (to my knowledge) has yet done this sort of history for a post-Mao, post-Socialist Chinese city and something as detailed and all encompassing as this would be fantastic. Publishers blurb: Fragile, gritty, and vital to an extraordinary degree, St. Petersburg is one of the world’s most alluring cities-a place in which the past is at once ubiquitous and inescapably controversial. Yet outsiders are far more familiar with the city’s pre-1917 and Second World War history than with its recent past. In this beautifully illustrated and highly original book, Catriona Kelly shows how creative engagement with the past has always been fundamental to St. Petersburg’s residents. Weaving together oral history, personal observation, literary and artistic texts, journalism, and archival materials, she traces the at times paradoxical feelings of anxiety and pride that were inspired by living in the city, both when it was socialist Leningrad, and now. Ranging from rubbish dumps to promenades, from the city’s glamorous center to its grimy outskirts, this ambitious book offers a compelling and always unexpected panorama of an extraordinary and elusive place.

Reading Catriona Kelly’s St Petersburg: Shadows of the Past I couldn’t help thinking that Shanghai or Beijing deserve similar books that really get under the skin of the city. Nobody (to my knowledge) has yet done this sort of history for a post-Mao, post-Socialist Chinese city and something as detailed and all encompassing as this would be fantastic. Publishers blurb: Fragile, gritty, and vital to an extraordinary degree, St. Petersburg is one of the world’s most alluring cities-a place in which the past is at once ubiquitous and inescapably controversial. Yet outsiders are far more familiar with the city’s pre-1917 and Second World War history than with its recent past. In this beautifully illustrated and highly original book, Catriona Kelly shows how creative engagement with the past has always been fundamental to St. Petersburg’s residents. Weaving together oral history, personal observation, literary and artistic texts, journalism, and archival materials, she traces the at times paradoxical feelings of anxiety and pride that were inspired by living in the city, both when it was socialist Leningrad, and now. Ranging from rubbish dumps to promenades, from the city’s glamorous center to its grimy outskirts, this ambitious book offers a compelling and always unexpected panorama of an extraordinary and elusive place.

Rob Baker’s Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics: A Sideways Look at Twentieth Century London also offers some guidance to how a seemingly random series of mini-histories and stories could reveal more of a city. Shanghai has a myriad of stories (as this blog attempts to show) and pulling them together to show the variety and randomness of urban life makes for great reading. Publishers blurb: Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics explores fascinating stories from London in the twentieth century. From the return to South London of local hero Charlie Chaplin to the protests that blighted the Miss World competition in 1970, the book covers the events and personalities that reflect the glamorous, scandalous, political and subversive place that London was and is today. Learn about, among many other captivating tales, exactly where and how the spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean spent their last ever day in London, the grisly murder of Stan the Spiv and the unlikely death of a defrocked girl-crazed priest. A cast of suffragettes, fascists, ‘nancy-boys’, showgirls, prostitutes, terrorists, Nippies and beauty queens features in stories containing a myriad of unexpected tangents and untold facts that cover the width and breadth of the world’s greatest city.

Rob Baker’s Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics: A Sideways Look at Twentieth Century London also offers some guidance to how a seemingly random series of mini-histories and stories could reveal more of a city. Shanghai has a myriad of stories (as this blog attempts to show) and pulling them together to show the variety and randomness of urban life makes for great reading. Publishers blurb: Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics explores fascinating stories from London in the twentieth century. From the return to South London of local hero Charlie Chaplin to the protests that blighted the Miss World competition in 1970, the book covers the events and personalities that reflect the glamorous, scandalous, political and subversive place that London was and is today. Learn about, among many other captivating tales, exactly where and how the spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean spent their last ever day in London, the grisly murder of Stan the Spiv and the unlikely death of a defrocked girl-crazed priest. A cast of suffragettes, fascists, ‘nancy-boys’, showgirls, prostitutes, terrorists, Nippies and beauty queens features in stories containing a myriad of unexpected tangents and untold facts that cover the width and breadth of the world’s greatest city.

David Burke’s The Lawn Road Flats: Spies, Writers and Artists takes one iconic block of flats in North London and dissects a slice of London society just before, during and after the war through the residents. Just about every old building in Shanghai or hutong in Beijing could provide a similar fascinating cornucopia of folk and tell a great story by interweaving them. Publishers blurb: The Isokon building, Lawn Road Flats, in Belsize Park on Hampstead’s lower slopes, is a remarkable building. The first modernist building in Britain to use reinforced concrete in domestic architecture, its construction demanded new building techniques. But the building was as remarkable for those who took up residence there as for the application of revolutionary building techniques. There were 32 Flats in all, and they became a haunt of some of the most prominent Soviet agents working against Britain in the 1930s and 40s, among them Arnold Deutsch, the controller of the group of Cambridge spies who came to be known as the “Magnificent Five” after the Western movie The Magnificent Seven; the photographer Edith Tudor-Hart; and Melita Norwood, the longest-serving Soviet spy in British espionage history. However, it wasn’t only spies who were attracted to the Lawn Road Flats, the Bauhaus exiles Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer; the pre-historian V. Gordon Childe; and the poet (and Bletchley Park intelligence officer) Charles Brasch all made their way there. A number of British artists, sculptors and writers were also drawn to the Flats, among them the sculptor and painter Henry Moore; the novelist Nicholas Monsarrat; and the crime writer Agatha Christie, who wrote her only spy novel N or M? in the Flats. The Isokon building boasted its own restaurant and dining club, where many of the Flats’ most famous residents rubbed shoulders with some of the most dangerous communist spies ever to operate in Britain. Agatha Christie often said that she invented her characters from what she observed going on around her. With the Kuczynskis – probably the most successful family of spies in the history of espionage – in residence, she would have had plenty of material.

David Burke’s The Lawn Road Flats: Spies, Writers and Artists takes one iconic block of flats in North London and dissects a slice of London society just before, during and after the war through the residents. Just about every old building in Shanghai or hutong in Beijing could provide a similar fascinating cornucopia of folk and tell a great story by interweaving them. Publishers blurb: The Isokon building, Lawn Road Flats, in Belsize Park on Hampstead’s lower slopes, is a remarkable building. The first modernist building in Britain to use reinforced concrete in domestic architecture, its construction demanded new building techniques. But the building was as remarkable for those who took up residence there as for the application of revolutionary building techniques. There were 32 Flats in all, and they became a haunt of some of the most prominent Soviet agents working against Britain in the 1930s and 40s, among them Arnold Deutsch, the controller of the group of Cambridge spies who came to be known as the “Magnificent Five” after the Western movie The Magnificent Seven; the photographer Edith Tudor-Hart; and Melita Norwood, the longest-serving Soviet spy in British espionage history. However, it wasn’t only spies who were attracted to the Lawn Road Flats, the Bauhaus exiles Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer; the pre-historian V. Gordon Childe; and the poet (and Bletchley Park intelligence officer) Charles Brasch all made their way there. A number of British artists, sculptors and writers were also drawn to the Flats, among them the sculptor and painter Henry Moore; the novelist Nicholas Monsarrat; and the crime writer Agatha Christie, who wrote her only spy novel N or M? in the Flats. The Isokon building boasted its own restaurant and dining club, where many of the Flats’ most famous residents rubbed shoulders with some of the most dangerous communist spies ever to operate in Britain. Agatha Christie often said that she invented her characters from what she observed going on around her. With the Kuczynskis – probably the most successful family of spies in the history of espionage – in residence, she would have had plenty of material.

Posted: December 10th, 2015 | No Comments »

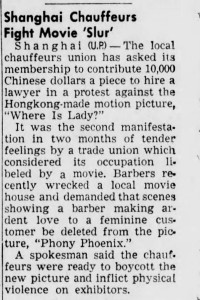

In 1947 just about everybody in Shanghai went on strike – mill workers of course but also barmen, prosties, taxi-dancers and even chauffeurs. Chauffeurs felt insulted by a Hong Kong movie called Where is Lady? Apparently barbers had recently got so angry at their portrayal in as amorous in another movie, Phony Phoenix, that they trashed a cinema (an activity usually done by Italians or Russians in Shanghai – see here and here respectively). The Union spokesman said they were ready to basically beat up anyone to do with the film!!

So what were these movies that so angered these groups of workers. I can’t find a movie called Where is Lady? but there was a 1947 movie from Hong Kong called Where is the Lady’s Home? that sounds like it might be the one. That was directed by Li Tie and starred Cheung Ying and the beautiful Siu Yin Fei (below) though how exactly this offended chauffeurs I’m not entirely sure.

Phony Phoenix is more commonly known in English as Fake Phoenix – another Hong Kong movie – perhaps the movie poster indicates why the barbers were a bit riled up!