All things old China - books, anecdotes, stories, podcasts, factoids & ramblings from the author Paul French

Posted: May 26th, 2016 | No Comments »

When you peruse an old Chinese newspaper or magazine, looks at all those old Shanghai calendar girl posters, gaze at old photos of Shanghai’s streets ever noticed just how many cigarette ads you see – and just how many brands seemed to be competing for the consumer? Hundreds. Well, that’s because it was totally crazy with so many competing brands…according to this short article, over a thousand brands in 1933…

Posted: May 25th, 2016 | No Comments »

The first is a fact that I never knew…and, yes even I, probably didn’t need to…

The second may or may not have been true…sadly, I can verify from numerous trips, it is no longer true and you now have to find the factory yourself nowadays…

Posted: May 24th, 2016 | No Comments »

We are now in the last days of Shanghai’s old town. With a few years, if not sooner, it will all be gone. There is no plan to keep anything; Shanghai’s urban planners have no interest in retaining, let alone restoring, any of the ancient buildings left within the district. This video, from Associated Press, shows the extent of the destruction and the failure of attention by the city to its own heritage and architecture. All too soon videos and photographs such as this will be all that remains of the old city as it now faces close to total extinction…

Posted: May 23rd, 2016 | No Comments »

I posted an old Shanghai Municipal Police “No Waiting” sign the other day; it was also the case that every telegraph pole was numbered in Shanghai too. Not sure where this one was but each pole had a sign like this….

Posted: May 22nd, 2016 | No Comments »

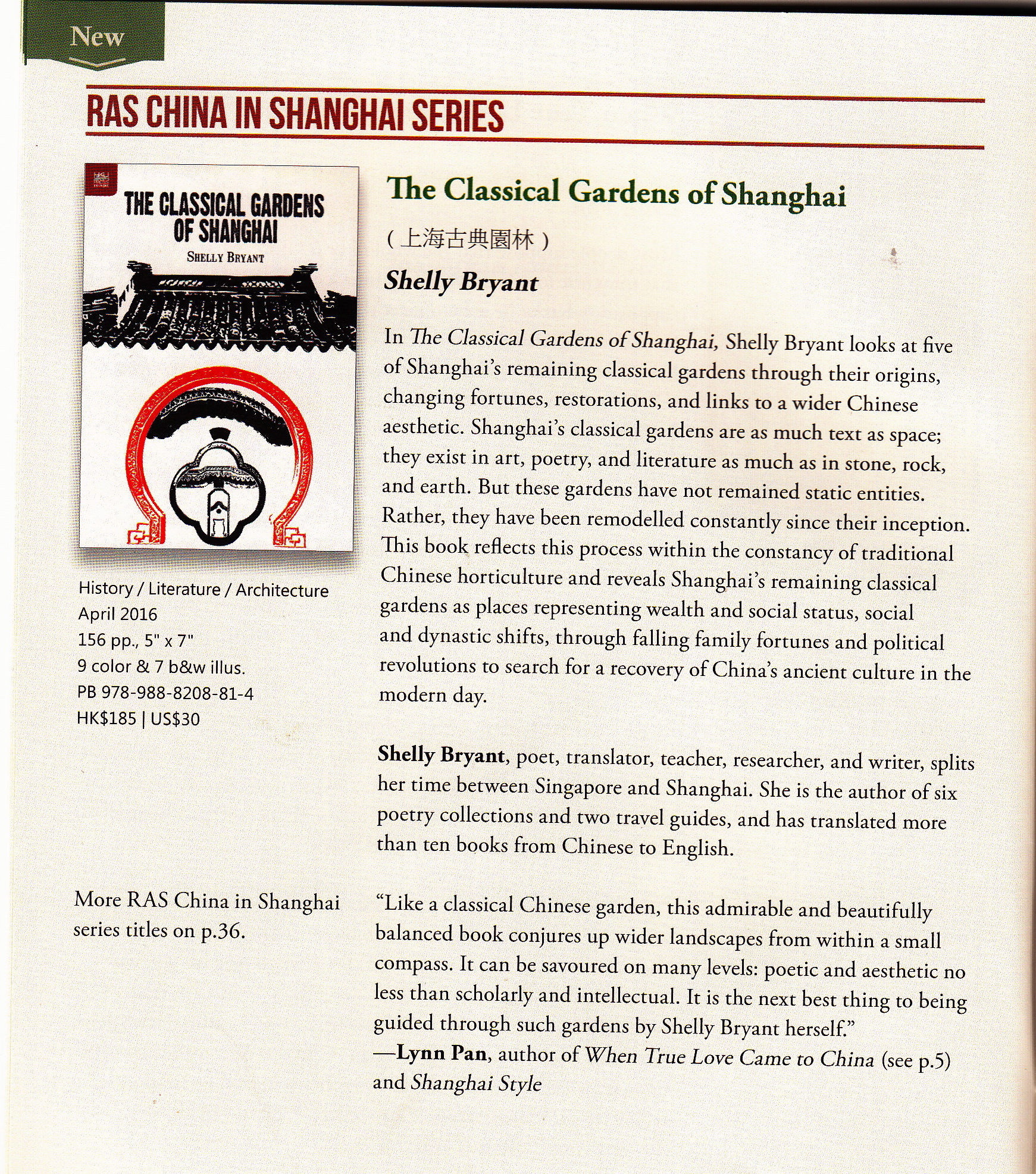

This week the Royal Asiatic Society China officially launched its fifth China Monograph – Shelly Bryant’s Classical Chinese Gardens of Shanghai. Here, for those who may have missed it, are details of that book…and a reminder of the others in the series…all available as either paperbacks or e-books…

Posted: May 21st, 2016 | No Comments »

Quite a few fridges in Shanghai in 1934…

Posted: May 20th, 2016 | 1 Comment »

The Camel Bell, a shop in the old Peking Hotel run for many years by American Helen Burton, is remembered in many memoirs of pre-war Peking. It specialised in silks, dresses, furs, Chinese curios and artworks and was a stop on just about every visitor or sojourners itinerary. Everyone went there, including Wallis Simpson and Helen Foster Snow modelled furs as a mannequin there to pick up a little extra cash. Burton arrived in 1921 and stayed until the war and eventually left on the famous Gripsholm evacuation ship.

What I didn’t know was that there was an American branch of the Camel Bell – in Bismarck, North Dakota. A strange location perhaps, but Burton originally came from Bismarck. Burton’s mother actually lived at 219 Bismarck Street, next to the address given for the store here in 1935. Every few years Burton would visit the US on “selling trips”, starting in Bismarck and then visiting various summer resorts in the Eastern seaboard states to show her wares from China.

Posted: May 19th, 2016 | No Comments »

OK, so this new Chinese restaurant in Kingston, NY might have been successful when it opened in 1934 – but only in America. No enterprising Chinese restaurateur in England would ever have named his establishment the “Shanghai Loo”!!