Posted: May 18th, 2016 | No Comments »

Sunday, 22nd May 2016

1:00 pm – 9:00 pm

Lu Xun Day

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS

1:00 pm – 3:30 pm, WALK: LU XUN AND FRIENDS IN SHANGHAI, meeting place TBA

4:30 pm – 6:00 pm, DISCUSSION: THE STORY OF A-Q, Chai Living Lounge

6:30 pm – 9:00 pm, FILM: “NEW YEAR SACRIFICEâ€, Chai Living Lounge

Three-part event. You may register for any one or two parts, or for all three parts.

Members, priority “Walk†registration through Wednesday, May 18. (Click here download membership application)

When registering, please indicate which event(s) you plan to attend. Please indicate if you wish to apply for or renew RAS membership.

RSVP bookings@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

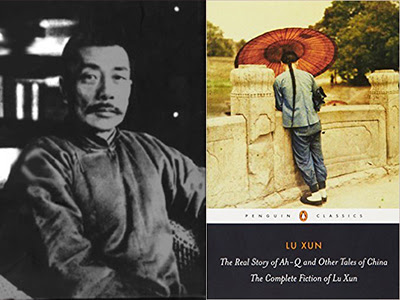

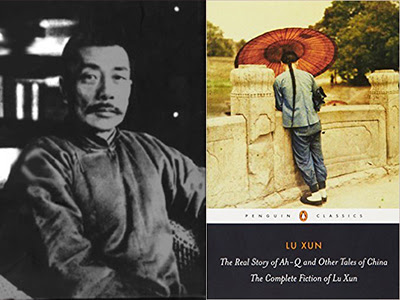

Lu Xun (1881-1936) is one of the greats of 20th-century Chinese literature. He was celebrated during and since his lifetime for his powerful diagnoses of his nation’s social and political crisis, and for his pioneering achievements in reinventing the vernacular as a literary language.

Despite his public commitment to Marxist literary ideals and his posthumous canonization by Mao Zedong, Lu Xun’s final years were spent mired in squabbles with the Chinese Communist Party’s representatives of ideological orthodoxy. When he died he bequeathed to modern Chinese letters a contradictory legacy of cosmopolitan independence, polemical fractiousness and anxious patriotism that continues to resonate in Chinese intellectual life today.

The Walk: Lu Xun and Friends in Shanghai From October 3, 1927, until his death October 19, 1936, Lu Xun lived in an area just outside Shanghai’s International Settlement but not quite within the jurisdiction of bordering Chinese administered Zhabei District. It was a political no man’s land making it a relatively safe place for left-wing activists to live and assemble. We will walk the streets Lu Xun walked, see some of the places where he and his fellow activists lived and met, and explore how, despite squabbles with the CCP during his lifetime, how he came to be one of its icons. (The house museum where he lived and died is temporarily closed for renovation). The area is in a part of Shanghai that at the time was heavily Japanese. During the walk we will see traces of its “Little Tokyo†past.

The Discussion: The Real Story of Ah-Q (阿Qæ£ä¼ ) is a novella first published as a serial between December 4, 1921 and February 12, 1922. Written after the May 4th Movement (1919), it is among the first pieces of Chinese literature written fully in the vernacular. In the story Ah-Q is continually defeated by his fellow lowlifes, by respectable people and by revolutionaries. Yet in his mind he turns each situation around into a moral victory. The work is generally held to be a masterpiece of modern Chinese literature.

The Film: New Year Sacrifice (ç¥ç¦), 1956

Directed by Sang Hu, Starring Bai Yang, Li Jingbo, Wei Heling, Guan Zhongqiang, Shi Lin, Screenwriter: Xia Yan, based on a story of the same name by Lu Xun, Cinematographer: Qian Jiang, Beijing Film Studio production

Linda Johnson, RAS Film Club convener, will introduce the film. This 1956 film version of the 1924 short story, a classic of revolutionary realism, was made as a commemoration of Lu Xun’s death 20 years before. It was the first film adaptation by Xia Yan in his new role as Deputy Minister of Culture. Many prominent filmmakers in China in the new Peoples’ Republic had been part of the May Fourth generation of artists and turned to literature of that period as a source for adaptations to mass culture. Xia Yan (1900-1995), arguably the most successful leftist writer in drama circles in Shanghai in the 1930’s and ‘40’s, was one such scriptwriter and he is seen here making dramatic changes to the narrative voice of the story, and to its content, to make it suitable for the mass culture of the day.

In Yan’an during the Sino-Japanese War Mao Zedong made it clear that the writings of the May Fourth ‘petit bourgeoisie’ had little connection with the Communist cause and directed writers to address wider concerns and wider audiences. As a result, the more complex, often ironic narrative styles were replaced with more traditional forms of storytelling and ambiguities in storylines were replaced with strong certainties. The director, Sang Hu, and his team of top ranking actors had also been prominent in pre-1949 Shanghai film, and this becomes evident in the quality of the performances and the attention to detail in the film.

The popularization of this story for the film version did not simply turn it into propagandist fodder for the masses, but produced a temporarily politically acceptable film, which appealed on a number of levels to both urban and rural public. It was an instant and widespread success, making the story a household name. Brilliantly portrayed on screen by Bai Yang (1920-1996), the character Xianglin’s Wife finally brought the feminist critiques of China’s patriarchal society by the New Culture Movement to a largely illiterate mass audience.

While it is not essential to have read the story before seeing the film it is interesting to see the type of adaptations made to popularize the story. The story is very short and can be found online at https://www.marxists.org/archive/lu-xun/1924/02/07.htm.

ENTRANCE

Walk Members RMB 100, non-members RMB 200

Discussion Complimentary for members and non-members joining walk, non-members RMB 50

Film Complimentary for members and non-members joining walk and/or discussion

VENUES

Walk Meeting place provided on acceptance of RSVP

Discussion and Film Chai Living Lounge, 410 North Suzhou Road, near Henan Middle Road虹å£åŒºå®¿å·žåŒ—è·¯410å·

Tiantong Road Metro Station, Lines 10 and 12

Posted: May 17th, 2016 | No Comments »

Quite a while back I appealed for any anecdotes or references to Chinese in North Africa in the 1930s, 1940s or 1950s. The Chinese get a mention in Casablanca and the French film Pepe Le Moko, while a Chinese-Vietnamese-French antique dealer in Marrakesh, called “Monsieur D.”, gets a mention in Peter Mayne’s memoir A Year in Marrakesh. Well, thanks to Anne Witchard’s wide ranging reading habits, I now know who the mysterious Monsieur D. was…and he was really quite someone…

According to Mayne, Monsieur D. rented a beautiful riad with gardens and a pavilion in the old town of Marrakesh. Mayne became friends with him and saw him working as an antique and curios dealer. He doesn’t give much more information.

However, Barbara Skelton, who married the author Cyril Connolly and then the publisher George Weidenfeld remembers Monsieur D. in the second volume of her autobiography, Weep No More (1989). Skelton met Monsieur D., who she refers to as Doan, through her own acquaintance with Peter Mayne. She describes him as a “Chinaman” with a great sense of humour and was working on a book about Indo-China. She also describes his eighteenth century riad – ‘stone floors, raffia mats and heavy cedarwood shutters’ and containing many Chinese antiques and birdcages. She also describes him as having a lisp and being obsessed with horoscopes.

A picture of Doan circa 1950s from Barbara Skelton’s Weep no More

A picture of Doan circa 1950s from Barbara Skelton’s Weep no More

Digging around a bit more it all really takes an amazing turn. It seems Doan was fully Raymond Doan who was technically Vietnamese, a trained chemist, had worked for a French oil company but was now in Marrakesh selling antiques and doing oil painting. He also fancied himself somewhat of a poet and this was how he wooed the heiress Barbara Hutton, heiress to the Woolworth fortune.

Hutton married a succession of interesting characters – seven in all – including Cary Grant, a self-styled Georgian Prince, a mitteleuropean Count, a championship tennis playing Baron, a white Russian prince, the Dominican diplomat and playboy Porfirio Rubirosa and finally Raymond Doan. None of the marriages was very successful. The marriage to Hutton came later, in the 1960s and after he had befriended Mayne and Skelton. Doan apparently wooed Hutton with his poetry while she was in Morocco, Tangiers to be precise. They married in 1964 and divorced in 1966. However, perhaps Doan exaggerated his position, or just never old Mayne or Skelton, for now he was described as Prince Pierre Raymond Doan and claiming to be an adopted son of the former Royal Family of the Kingdom of Champasak (in what is now Laos and reduced from a Kingdom to a mere province of Indo-China in 1946). However, a formal adoption seems unlikely and the rumour mill says Hutton bought Doan the title from the Laotian embassy in Rabat.

Hutton and Doan

Hutton and Doan

Doan was Hutton’s last husband – she died in 1979 still calling herself the Princess Raymond Doan Vinh Na Champassak…

Posted: May 17th, 2016 | No Comments »

Very happy to finally get to the official launch of Shelly Bryant’s The Classical Gardens of Shanghai – book number 5 in the Royal Asiatic Society Shanghai China Monographs series I edit….

Wednesday, 18th May 2016

7:00 pm – 9:00 pm

SOFA, Fuzhou Lu

Author: Shelly Bryant

In The Classical Gardens of Shanghai, Shelly Bryant looks at five of Shanghai’s remaining classical gardens through their origins, changing fortunes, restorations, and links to a wider Chinese aesthetic.

Shanghai’s classical gardens are as much text as space; they exist in art, poetry, and literature as much as in stone, rock, and earth. But these gardens have not remained static entities. Rather, they have been remodeled constantly since their inception.

This book reflects this process within the constancy of traditional Chinese horticulture, and reveals Shanghai’s remaining classical gardens as places representing wealth and social status, social and dynamic shifts through falling family fortunes and political revolutions to search for a recovery of China’s ancient culture in the modern day.

‘Like a classical garden, this admirably and beautifully balanced book conjures up wider landscapes from within a small compass. It can be savoured on many levels: poetic and aesthetic, no les than scholarly and intellectual. It is the next best thing to being guided through such gardens by Shelly Bryant herself.†– Lynn Pan, author of When True Love Came to China

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Shelly Bryant, a poet, translator, teacher, researcher and writer, splits her time between Singapore and Shanghai. She is the author of six poetry collections and two travel guides, and has translated more than ten books from Chinese to English.

Posted: May 16th, 2016 | No Comments »

Often old Shanghai photos don’t quite give us a sense of what life was really like at ground level…we need to zoom in. I’ve been doing that lately to try and get a sense of old Shanghai’s “street furniture”, the official signage that would have been ubiquitous across the Settlement but often gets missed in photos. Here then is a Shanghai Municipal Police “No Waiting” sign, of which there were probably dozens if not hundreds across the Settlement….

Posted: May 15th, 2016 | No Comments »

RAS Shanghai Film Club

Sunday, 22nd May 2016

6:30 pm – 9:00 pm

Chai Lounge at Chai Living Gallery

Zhu Fu, New Year’s Sacrifice, 1956

Directed by Sang Hu

Cast: Bai Yang, Li Jingbo, Wei Heling, Guan Zhongqiang, Shi Lin

Screenwriter: Xia Yan, based on a story by Lu Xun

Cinematographer: Qian Jiang

A Beijing Film Studio production

(THIS EVENT IS PART OF RAS WEEKENDER – LUXUN DAY THAT INCLUDES A WALK, BOOK DISCUSSION AND FILM CLUB)

The 1924 short story by Lu Xun, New Year’s Sacrifice was first adapted to performance in 1946 as an underground Yue Opera, staged to commemorate Lu Xun’s death 10 years earlier and as a rallying cry for Shanghai Communists oppressed by Nationalist rule. New Year’s Sacrifice tells the story of the tragic life of a countrywoman blighted by the weight of tradition, superstition and the low status of women. The misfortunes she endures are harsh, relentless and patently unconnected with her own agency. As an opera it appeared on the silver screen in 1948 and after the founding of the PRC many performances of the original opera and multiple adaptations were staged. This 1956 film version of the story, a classic of revolutionary realism, was also made as a commemoration of Lu Xun’s death, and was the first film adaptation by Xia Yan in his new role as Deputy Minister of Culture. Many prominent filmmakers in China in the new Peoples’ Republic had been part of the May Fourth generation of artists and turned to literature of that period as a source for adaptations to mass culture. Xia Yan (1900-1995), arguably the most successful leftist writer in drama circles in Shanghai in the 1930’s and ‘40’s, was one such scriptwriter and he is seen here making dramatic changes to the narrative voice of the story, and to its content, to make it suitable for the mass culture of the day. The most outstanding change from the story to the film is the removal of Lu Xun as narrator, a device in the story that strongly conveys the doubt, isolation and moral creativity involved in turning away from traditional values, whilst allowing the story of Xian Ling’s wife to amply demonstrate the consequences of traditionalism. Removing the narrator and chronologically following the oppressive experiences of Xian Ling’s wife, shifts the focus from the individual to the state, making progressive state reform the categorical saviour of the oppressed.

During his time in Yan’an during the Sino-Japanese War Mao Zedong made it clear that the writings of the May Fourth ‘petit bourgeoisie’ had little connection with the Communist cause and directed writers to address wider concerns and wider audiences. As a result, the more complex, often ironic narrative styles were replaced with more traditional forms of storytelling and ambiguities in storylines were replaced with strong certainties. This film version leaves no doubt as to the message of the story. It opens with an off-screen voice saying “For young people today, this is a story of long, long ago. About 40 years ago, around the time of the 1911 revolution, in a remote village in Zhejiang …†and ends with the same voice saying “This happened more than 40 years ago. Yes, this is a thing of the past. What we should celebrate is that times like these finally passed on. They are over, and will not return.â€

The director, Sang Hu, and his team of top ranking actors had also been prominent in pre-1949 Shanghai film, and this becomes evident in the quality of the performances and the attention to detail in the film. The sequence introducing the Lin family to the audience, for example focuses first on the plaque above the entrance to their mansion, the New Year’s slogans freshly written by the master of the house who is teaching his grandson calligraphy, all of which was addressed to educated Chinese who would appreciate the literary culture on display. The popularisation of this story for the film version did not simply turn it into propagandist fodder for the masses, but produced a temporarily politically acceptable film, which appealed on a number of levels to both urban and rural public. It was an instant and widespread success, making the story a household name. Brilliantly portrayed by Bai Yang (1920-1996), Xianglin’s Wife on screen finally brought the feminist critiques of China’s patriarchal society by the New Culture Movement to a largely illiterate mass audience.

The number of films made during the “Seventeen Years†Period that were based upon May 4th literature has been seen as ironic, considering Mao’s negativity towards Western-influenced May 4th writers in the 1940’s. Yet the literary cachet these films carried assured audiences that the narrative would be high quality and, perhaps more importantly, marked by Shanghai’s past, rather than by Hollywood. The mildly progressive politics of the mid-1950’s to early 1960’s also permitted their use in mass media, although those involved later fell foul of Jiang Qing’s strictures as the Cultural revolution got underway. They were certainly hugely successful at the box office and the mismatch between early modernist literature and socialist realism gave them a kind of endearing awkwardness that later films lacked. Of all of them, New Year’s Sacrifice has generally been considered the most successful of them all because of Xia Yan’s adaptation and the direction of Second Generation great Sang Hu. The film appears amongst Asia Weekly’s authoritative list of the 100 Greatest Chinese Films of the Twentieth Century.

While it is not essential to have read the story before seeing the film it is interesting to see the type of adaptations made to popularise the story. The story is very short and can be found online at https://www.marxists.org/archive/lu-xun/1924/02/07.htm

RSVP: filmclub@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

ENTRANCE: FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT TICKET PRICE SEE RAS WEEKENDER LUXUN DAY: RMB

VENUE: Chai Lounge at Chai Living Gallery; Embankment Bg, 370 Beisuzhou Lu, near Sichuan Lu Shanghai

Posted: May 14th, 2016 | No Comments »

Tickets for events at the Frontline tend to sell out rather fast, so here’s a heads up – I’ll be moderating the event below with a great panel on June 1st…

One Child: A Portrait of Modern China

June 1, 7pm

Frontline – London

In 1980, China instigated one of the most radical social experiments in human history. The one child policy has long defined the family and wider society in China – but at the end of the last year a major shift took place when Beijing announced a nationwide two-child policy.

We will be discussing how the one child policy has come to shape the fabric of modern China, as well as the repercussions it has had. From the significant gender imbalance to the dramatically raging population, what can we learn from this social experiment and what does it mean for China’s future?

Chaired by Paul French, an author and widely published analyst and commentator on Asia, Asian politics and current affairs. He is author of North Korea: State of Paranoia and the international bestseller Midnight in Peking.

The panel:

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is chancellor’s professor of history at the University of California, Irvine, and editor of the Journal of Asian Studies. He has edited a number of books on China and is the author of four including China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know.

Mei Fong is a journalist with more than a decade of reporting in Asia, most recently as China correspondent for The Wall Street Journal. She is the author of One Child: The Past and Future of China’s Most Radical Experiment.

Isabel Hilton is a journalist, broadcaster and writer. She is the founder and editor of chinadialogue and has authored and co-authored several books and holds honorary doctorates from Bradford and Stirling Universities. She was appointed OBE in 2010 for her contribution to raising environmental awareness in China.

Details and booking here

Posted: May 12th, 2016 | No Comments »

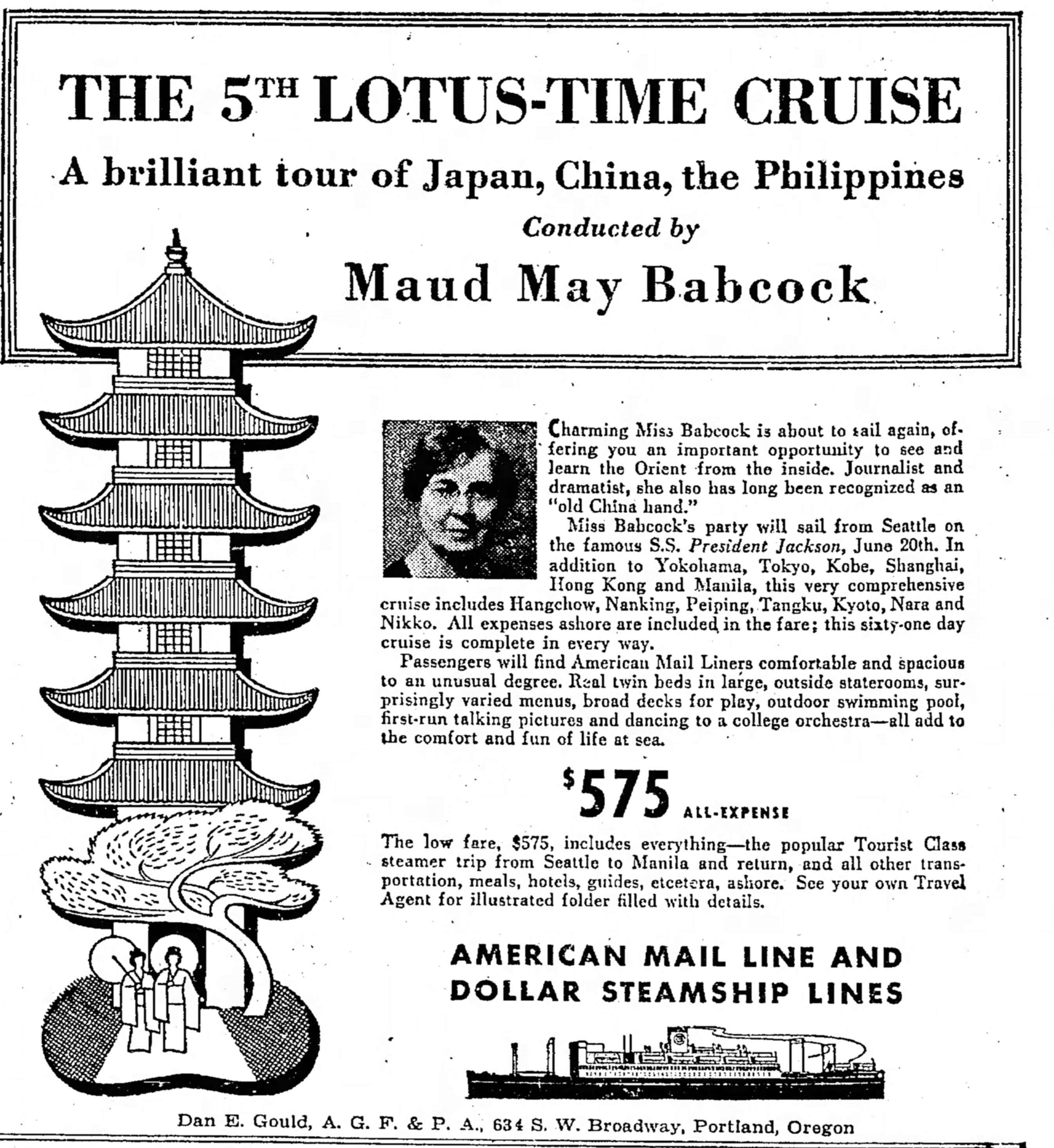

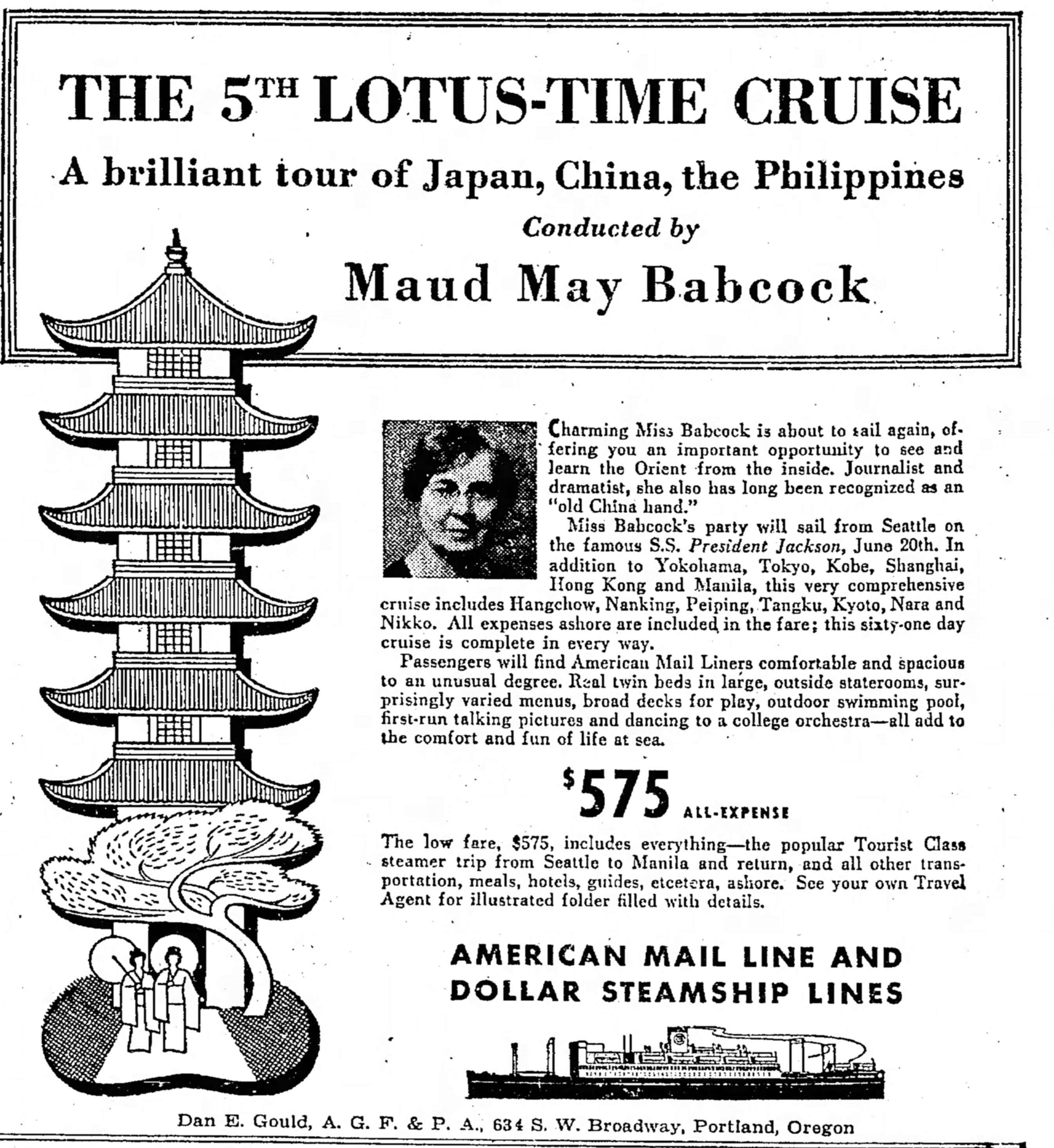

Looking for a holiday in 1936 with a bit of a difference? How about the “Lotus-Time Cruise” round Asia with the Dollar steamship line in the company of Maud May Babcock? Let me explain the details:

- Arguably it’s not a bad deal – $575 in 1936 is about $10,000 today – and its all inclusive, your meals, transfers, cabin and Maud May’s company;

- You’ll get to see loads of places including Shanghai and Peking;

- It’s a nice ship – not like doing it all China Eastern or Air Asia – the SS President Jackson’s a nice bunk;

- There are a lot of extras included in your $575 – a pool, movies, varied menus, dancing to a “college orchestra” (not sure what that is!);

- And it’s all in the company of Miss Babcock, who, the advert reassures us is an “Old China Hand”

Now while I believe the itinerary, the good price and the extras I’m not sure I buy Miss Babcock as an “Old China Hand”. Sure, she was known for many amazing things such as: she was recruited to the Mormons by a daughter of Brigham Young; she was as teacher of speech and drama across the USA and in London; she was a tiresome campaigner against wasp waist corsets but I’m not at all sure about her China credentials.

OK, she does seem to have visited Asia and taken an interest – later that interest involved her in the Aid China movement during the war. However, she was little more than a tourist herself to the Far East – let’s move her up to the rank of temporary sojourner. However, the only photographs in her archive (at the University of Utah) of China are taken on this trip advertised below. Anyway, I’m sure it was a lovely trip…..

SS President Jackson

Posted: May 11th, 2016 | No Comments »

1930 and an apparently excellent “cocktail artist” (nowadayas they like to be known as “mixologists”; most of us know them less prosaically as “barmen”) wants a job in Shanghai. Not a bad choice – cocktails were becoming quite the thing, though he might have found himself spending his most of his time mixing simple stengahs and chota pegs. I wonder if ever got a job and, if so, where?