Posted: August 21st, 2015 | No Comments »

As tensions escalated in and around Shanghai in late 1940 the US State Department ordered children (and suggested wives) be evacuated aboard refugee ships back to America. Here then, from December 1940, are the children of George Monk, an American businessman in Shanghai, being waved off as they board a lighter in Shanghai to get them to the refugee ship moored down at Woosong (Wusung).

I think George Monk, was George B. Monk, who was in charge of the Shanghai branch of A.C. Monk & Co., a wholesaler of tobacco based in Farmville, North Carolina. Monk received the shipments of tobacco from the United States, stored them in the China warehouses and hired an office force of between ten and twelve people (including presumably Mr Clem Breen pictured below). Monk returned to the US in 1941.

Posted: August 20th, 2015 | No Comments »

Rebecca Wue’s Art Worlds looks like a must-have…..there’s a review from the Asian Review of Books here….

The growth of Shanghai in the late nineteenth century gave rise to an exciting new art world in which a flourishing market in popular art became a highly visible part of the treaty port’s commercialized culture. Art Worlds examines the relationship between the city’s visual artists and their urban audiences. Through a discussion of images ranging from fashionable painted fans to lithograph-illustrated magazines, the book explores how popular art intersected with broader cultural trends. It also investigates the multiple roles played by the modern Chinese artist as image-maker, entrepreneur, celebrity and urban sojourner. Focusing on industrially produced images, mass advertisements and other hitherto neglected sources, the book offers a new interpretation of late Qing visual culture at a watershed moment in the history of modern Chinese art. Art Worlds will be of interest to scholars of art history and to anyone with an interest in the cultural history of modern China.

Posted: August 20th, 2015 | No Comments »

A good American business success in China here – from 1929. Ryan Planes, founded by T. Claude Ryan in San Diego in 1922, built the Spirit of St Louis for Lindbergh to cross the Atlantic in in 1927. That historic flight certainly inspired early aviators and aviation pioneers in China. In 1929 Carl Crow reported in the American newspapers that China had ordered and received (for the price of US$135,000 in 1929 money) five Ryan planes for service on the Hankow-Canton passenger line run by the Wuhan Aviation Bureau. I think these planes were technically Ryan B-1 Broughams. After Lindbergh’s successful flight Ryan built about 200 Broughams in 1927 for general sale. Clearly the planes were shipped out to China and reassembled after arrival by Earl Baskey of the Mahoney Aircraft Corporation – Frank Mahoney was a partner of Ryan’s who seems to have been the power behind the business.

The planes were given great names – The Spirit of Canton, The Spirit of Chukiang etc. Several Ryan planes had arrived in China earlier, bought by another aviation start up – there’s detail of those and a picture here.

This incredible picture shows Chinese workers (labelled “coolies”) pulling one of the reassembled Ryan Brougham’s through the streets to the airfield (we can assume this was a publicity stunt as otherwise why not assemble the planes at the airfield?)

Baskey is an interesting character in this story as he ended up spending four years in China. He got his wings around 1918 (probably a WW1 pilot – the China Monthly Review listed him as a former Squadron Commander) and then flew mail planes on the St. Louis-Chicago (with a quick stop at Rantoul, Ill for gas and oil) route. In 1924 he enterprisingly bought his own plane to tour round county fairs offering rides and also became the special Aeronautical Deputy Sheriff of Sandursky County, Ohio. In China, after delivering the Ryan planes and reassembling them in Hankow and inaugurating the 700-mile route, it seems he stayed on promoting and selling American aircraft to fledgling Chinese airlines. In 1938 he was called up and flew in WW2 with the rank of Major. He died in the 1980s in Fort Myers.

Posted: August 19th, 2015 | No Comments »

This picture shows the randomness of war in Shanghai after the Japanese invasion of the Chinese portions of the city in 1937. This is early 1938 and a Chinese bomb, aimed at Japanese warships moored on the Whangpoo (Huangpu) River has missed its target and landed in Pootung (Pudong) hitting a British-owned wharf and go-down. Judging by the smoke from the explosion I think we can assume not much was left of the facility…

Posted: August 18th, 2015 | 1 Comment »

Has Hong Kong pushed some sort of heritage self-destruct button? In a week or so the following….

400-year-old Banyans slashed to destruction on Bonham Road

Thousands of classic neon signs ordered to be removed

One of only a trio of surviving rounded corner buildings demolished in Wan Chai

And now something that calls itself (yes, it really does…) Intellects Consultancy is recommending shutting down the tram lines and services in Central as they cause traffic congestion (yes, that’s their “intellect” – it’s the trams full of passengers – about 194,000 of them per day onboard) that cause the congestion, not the cars with one occupant!!)

Posted: August 17th, 2015 | No Comments »

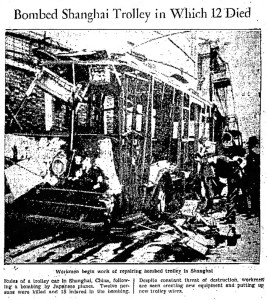

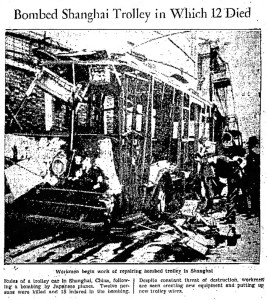

This deadly image of a Shanghai trolleybus in early 1938 which has taken a hit from a Japanese plane flying over Shanghai. The trolleycar is obviously gutted and twelve people reportedly died in the blast with another eighteen injured. However, the fact that the workmen are moving immediately to get the trolley wires back up shows the determination to resist and keep Shanghai’s public transport system working despite the Japanese attack….

Posted: August 16th, 2015 | No Comments »

Gregory Moore’s new history of Roosevelt and the Open Door Policy looks interesting….

There has been little examination of the China policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration. Works dealing with the topic fall either into brief discussions in biographies of Roosevelt, general surveys of Sino-American relations, or studies of special topics, such as the Chinese exclusion issue, which encompass a portion of the Roosevelt years. Moreover, the subject has been overshadowed somewhat by studies of problems between Japan and the United States in this era. The goal of this study is to offer a more complete examination of the American relationship with China during Roosevelt’s presidency. The focus will be on the discussion of major issues and concerns in the relationship of the two nations from the time Roosevelt took office until he left, something that this book does for the first time. Greater emphasis needs to be placed on creating a more complete picture of Teddy Roosevelt and China relations, especially in regard to his and his advisers’ perceptual framework of that region and its impact upon the making of China policy. The goal of this study is to begin that process. Special attention is paid to the question of how Roosevelt and the members of his administration viewed China, as it is believed that their viewpoints, which were prejudicial, were very instrumental in how they chose to deal with China and the question of the Open Door. The emphasis on the role of stereotyping gives the book a particularly unique point of view. Readers will be made aware of the difficulties of making foreign policy under challenging conditions, but also of how the attitudes and perceptions of policymakers can shape the direction that those policies can take. A critical argument of the book is that a stereotyped perception of China and its people inhibited American policy responses toward the Chinese state in Roosevelt’s Administration. While Roosevelt’s attitudes regarding white supremacy have been discussed elsewhere, a fuller consideration of how his views affected the making of foreign policy, particularly China policy, is needed, especially now that Sino-American relations today are of great concern.

Posted: August 15th, 2015 | No Comments »

Just realised that I have inadvertently contributed to an outbreak of of spooky spectral behaviour in the media and among Asia-Watchers as we hit the 70th anniversary of World War Two. “Ghosts”, it seems, appear to be the theme everyone’s going for….

Here’s me in The Diplomat on The Lingering Ghosts of World War Two in Asia

CCTV went for Ghosts of World War Two Haunt East Asia

The Economist went for Asia’s Second World War Ghosts

India’s NDTV also went for Ghosts of World War Two Haunt Asia

America’s The National Interest went for The Ghosts of World War II are Persistent Things

Australia’s The Conversation went for the slightly odd The Living Ghosts of 1945 Haunt Asia’s Rival Powers (sorry, but aren’t ghosts dead by definition?)

And many, many more around online and still to come I imagine….