New York’s Chinatown

Posted: April 6th, 2014 | No Comments »China Rhyming is away in New York this week and taking a short break from posting…so here’s a few shots of Manhattan’s old Chinatown….

All things old China - books, anecdotes, stories, podcasts, factoids & ramblings from the author Paul French

China Rhyming is away in New York this week and taking a short break from posting…so here’s a few shots of Manhattan’s old Chinatown….

An interesting piece by Bill Lascher in Boom: A Journal of California. It’s about radio station XGOY and a dentist in Ventura, California who was the station’s contact in the U.S.

RAS LECTURE

Tuesday 8 April 7:00 for 7:15 PM

RAS Library at the Sino-British College

1195 Fuxing Zhong Lu

Â

Non Arkaraprasertkul

PhD Candidate in Anthropology, Harvard University

Harvard Asia Center Affiliate, Harvard Center Shanghai

Â

speaking on

Â

“Housing and Heritage: Political Economy and Urban Space in Shanghai Lilong Neighborhoods”

In massive development projects that often directly affect “traditional” Shanghai neighborhoods, the city’s local government has drawn urban planning inspiration from cities such as New York, London, and Tokyo, which have achieved architectural distinction as “global cities” by combining modern high-rise and heritage buildings. City branding is a major part of Shanghai’s urban development program, and the preservation of historic buildings is seen as integral to this emerging brand. The underlying rationale is to protect “architectural artifacts” that the local government considers appropriate for a city with global ambitions. The central question, however, is: how does the image of urban globalization affect the citizenry whose lives the city government is claiming to improve? More broadly, the politically charged context of “traditional” neighborhood preservation situates contested forms of expertise mobilized by local government actors, neighborhood residents, and architects and planners.

Â

As a result, old neighborhoods have been removed to make way for modern high-rises, condominiums, office and commercial buildings, and so on. In the process, not only are people forced from their homes, but their displacement also raises the critical question: what Shanghai should be as a city, whom it should serve – whether that should be the local population or global commerce. Exemplifying this issue are contestations surrounding the traditional alleyway houses of Shanghai known as lilong. Literally meaning “neighborhood lane,” the lilong (里弄) are the legacies of Shanghai’s Treaty Port era (1842-1946), representing the Chinese take on the British row house aesthetic. The lilong also constituted the primary housing stock found in Shanghai up until the early 1980s, with multiple generations having occupied the same dwellings for 100 years or more.

Â

Historians, journalists, and architects often share the opinion that lilong neighborhoods are historically important and, therefore, must be preserved. In many ways the attitude underlying this opinion – based as it is on a Eurocentric notion of the global city – encourages the local government’s romanticization of Shanghai’s neighborhood life, similar to the gradually disappearing courtyard houses in Beijing (“hutong,” 胡åŒ). In this presentation, I will present my ongoing doctoral research regarding the sociopolitical conflicts over the intertwined issues of heritage, urban space, and human rights – in which the lilong is at the center.

About Non Arkaraprasertkul

Trained as an architect, urban designer, historian and ethnographic filmmaker, Non Arkaraprasertkul is currently a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at Harvard University. He has published widely in the fields of urban studies, architectural history, and urban anthropology. His research interest lies in the crossroad of transdiscliplinary research between architecture and the social sciences. In the spring of 2013, he served as Distinguished (Visiting) Gibbons Professor of Architecture at the University of South Florida (USF). Previously, he was a visiting lecturer in Architecture and Urban Design at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2007-2008, and an adjunct professor in Modern Chinese History at Lesley University from 2012 to present.Â

Â

Non has master’s degrees in history, theory, criticism of architecture, and architecture and urban design from MIT, and Modern Chinese Studies from the University of Oxford. From September 2013, he will be based at Fudan University as Harvard-China Council Exchange Scholar and at Harvard Shanghai Center as Harvard Asian Center Affiliate conducting his doctoral research “Locating Shanghai: Globalization, Heritage Industry, and the Political Economy of Urban Space.” He can be reached at non@mit.edu.

RSVP: to RAS Bookings at: bookings@royalasiaticsociety.

Â

ENTRANCE CONTRIBUTION: Members 50 RMB Non-members 70 RMB. Includes a glass of wine or soft drink. Priority for RAS members. Those unable to make the donation but wishing to attend may contact us for exemption.

Â

MEMBERSHIP applications and membership renewals will be available at this event.

Â

RAS MONOGRAPHS – Series 1 & 2 will be available for sale at this event. 100 rmb each (cash sale only)

Â

WEBSITE: www.royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

Well done to Camphor Press down in Taiwan for reissuing Gunther Pluschow’s The Aviator of Tsingtao….an amazing story (see below)

Gunther Plüschow: pioneering First World War pilot, aerial explorer, bestselling writer, the only German prisoner of either world war to break out of a POW camp in Britain and escape back to Germany, and perhaps the very first flyer to ever down an aircraft in combat. During the Battle of Tsingtao, where overwhelming Japanese and British forces attacked the German enclave in China, Plüschow was the defenders’ lone pilot.

The Aviator of Tsingtao is Plüschow’s gripping account of his wartime flying adventures, and his escapes from both China and England. This Camphor Press edition comes with new notes, maps, a timeline, photographs, and an introduction by Plüschow biographer, Anton Rippon.

Yesterday I posted about the new 3 volume collection of the etchings of Mortimer Menpes. I briefly mentioned his London apartment at 25 Cadogan Gardens (just off Sloane Street, in Knightsbridge) and that it Japanois/Chinois in style and designed by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942), a progressive English architect and designer who influence the Arts and Crafts Movement. Menpes lived in the apartment from the late 1880s to 1900.

In 1899 the magazine, The Studio: an Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art featured Menpes/Mackmurdo’s interiors for 25 Cadogen Gardens. Below that is the exterior of the building from roughly the same time

“The drawing room at 25 Cadogan Gardens, Mr. Mortimer Menpes’ House – The small square wooden tables in the drawing-room are of Chinese form and useful for the reception of ornamental objects”

“The drawing room at 25 Cadogan Gardens, Mr. Mortimer Menpes’ House – The small square wooden tables in the drawing-room are of Chinese form and useful for the reception of ornamental objects”

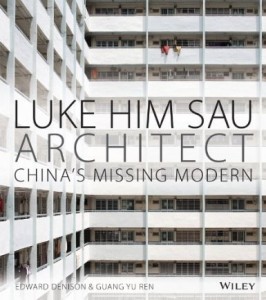

Another event, this time in Beijing, for Ed Denison’s new book on Luke Him Sau:

This talk examines China’s architectural encounters in the first half of the 20th-century through the lens of one of the country’s most distinguished yet overlooked practitioners: Luke Him Sau (Lu Qianshou, 1904–1991).

Luke is best known internationally and in China as the architect of the iconic Bank of China Headquarters in Shanghai. One of the first Chinese students to be trained at the Architectural Association in London in the late 1920s, Luke’s long, prolific and highly successful career in China and Hong Kong offers unique insights into an extraordinary period of Chinese political turbulence that scuppered the professional prospects and historical recognition of so many of his colleagues.

The story of Luke’s life begins with his childhood in colonial Hong Kong and his apprenticeship with a British architectural firm, before travelling to London to study at the prestigious Architectural Association (1927–30). In London, Luke was offered the post of Head of the Architecture Department at the newly established Bank of China and spent the next seven years in the inimitable city of Shanghai.

From his Shanghai base, he designed buildings all over China for the Bank and other clients before the Japanese invasion in 1937 forced him, and countless others, to flee to the proxy wartime capital of Chongqing. After the war he returned to Shanghai where he formed a partnership with four other Chinese graduates of UK universities; but civil war (between the Communists and Nationalists) once again caused him and others to uproot in 1949.

Initially intent on fleeing with the Nationalists to Taiwan, Luke was almost convinced to stay in Communist China by his friend and fellow architect, Liang Sicheng, but decided finally to move to Hong Kong. There, for the third time in his life, he had to establish his career all over again. Despite many challenges, he eventually prospered, becoming a pioneer in the design of private residences, schools, hospitals, chapels and public housing.

Edward Denison

(architectural historian, writer and photographer) and Guang Yu Ren (architect, researcher and independent consultant) have nearly two decades of international professional experience in architecture and design. They have worked extensively in the UK, China and Africa and authored numerous books based on their projects. These include: Building Shanghai – The Story of China’s Gateway (John Wiley & Sons, 2006), Modernism in China – Architectural Visions and Revolutions (Wiley, 2008), The Life of the British Home – An Architectural History (Wiley, 2012) McMorran & Whitby (RIBA, 2009) and Asmara: Africa’s Secret Modernist City (Merrell, 2003). They are now based in London where Edward is a Research Associate and teaches architectural history and theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London (UCL) and is a teacher at New York University in London.

Hua Xiahong

Associate Professor of Department of Architecture College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University. Phd. in Architectural History and Theory. A main researcher of Hudec Architecture in Mainland China. Author of Shanghai Hudec Architecture in Chinese. Part-time editor of Time Architecture magazine.Â

Published essays: – Modern China’s consuming dream and architecture carnival: since 1992; – Hanging Courtyard The Design Strategy for Blocks B4/B5 of Shanghai Culture & Communication Industry District.

Wang Haoyu

Phd in Architecture, The University of Hong Kong. Research in Modern Chinese Architecture History, Hong Kong Urban Architecture History and Architectural Heritage Protection and Management.

Author of – Architects from Mainland China to Hong Kong after 1949; – Interviewing Mr. Luke Him Sau’s descendants in Hong Kong: A case study of a pioneer modern Chinese architect; and Mainland architects in Hong Kong after 1949: a bifurcated history of modern Chinese architecture.

I was first introduced to the Australian/British artist Menpes by Jonathan Wattis, of Wattis Fine Arts in Hong Kong, who had a few of his etchings in stock once when I popped in there. Menpes was an Adelaide boy but studied art in London and was a pupil and flat mate of James McNeill Whistler.

Now, and here’s what interests us all at China Rhyming, he visited Japan in 1887 and was greatly influenced there. He returned to live on London’s Cadogan Square, a flat he decorated in Japanois style (by AH Mackmurdo of the arts and crafts movement). Whistler and Menpes fell out in 1888 over the interior design of the house, which Whistler felt was a brazen copying of his own ideas.

Later in 1902 Menpes headed east again visiting China, Burma and Japan among other places. His sketches and drawings from these trips are wonderful and now available as a three volume set by Gary Morgan – The Etched Works of Mortimer Menpes. I assume, as the books run chronologically that Volume II – covering 1901 to 1913 is the most relevant. Anyway – they’re all here