Posted: March 3rd, 2014 | No Comments »

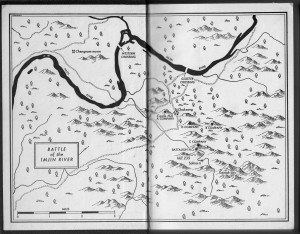

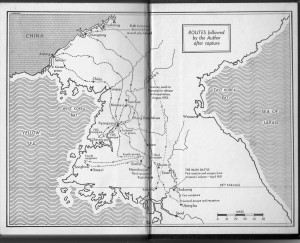

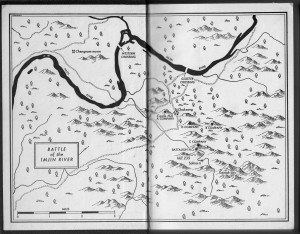

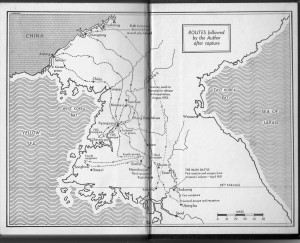

My mother was a member of the Companion Book Club in the 1950s (before I came along) and recently I came across a box of books from the Club she must have received around the mid-50s. It included a few interesting books that feature China, though she had no personal interest in the place and they were among the more usual fodder of long-forgotten romances and things like Lorna Doone. I feel, via the Companion Club, she was a voracious reader of what George Orwell termed “Good Bad Books” in an essay. I’m not sure how much she would have enjoyed Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley’s The Edge of the Sword, but as an occasional Korea Hand I rather liked it. It’s the story of the Gloucestershire Regiments (the Glorious Gloucesters) in the Korean War, a well known story at the time. It follows their epic battle at the Imjin River and Farrar-Hockley’s capture by the Chinese and imprisonment by them for two and a half years.

Farrar-Hockley was kept in the Pyongyang Political Prison and subjected to psychological torture before escaping out through North Korea, a quite remarkable adventure. The book comes with two interesting maps (below), one of the Battle of the Imjin River and the other of the author’s escape route.

Posted: March 2nd, 2014 | 1 Comment »

Last week’s post on Carl Van Vechten reminded me that he shot a portrait of the author Thomas Handforth. Handforth (1897-1948), an American artist and teacher, is now best remembered for his children’s book Mei Li that was based on his experiences of China (and a real girl he met there) and has remained (at least until fairly recently) a perennial favourite kids book. It won the Caldecott Medal for illustration. The story deals with a young Chinese girl’s visit to a Chinese New Year festival in the countryside. It’s perhaps not the most politically correct book these days but the illustrations were charming (a selection below)….Handworth’s art was inspired by being given a book of Housaki’s drawings early on. In 1931 Handforth received a Guggenheim Fellowship for travel to China. He expected to spend two weeks in Peking, but stayed for six years, renting a space in an old courtyard house that had fallen into disrepair. In China he moved from etching to lithography because he felt that the spirit of China was better captured with a brush and a “greasy crayon.†The real Mei Li was the youngest of four Chinese girls adopted by Helen Burton, an extremely well known and well connected American woman in Peking who owned The Camel’s Bell Shop in the lobby of the Peking Hotel (A good bio of Burton remains to be written I think – unless there’s one I don’t know about?)

Handforth by Van Vechten

Handforth by Van Vechten

Posted: February 28th, 2014 | No Comments »

Crazily this exhibition has only run for a short time but if you’re in Hong Kong you can get over and see it at the Hong Kong Museum of History – it ends on the 3rd March. There’s a long review here and a link to the exhibit here. Sorry, to leave it a bit late!

Hong Kong’s cheongsam culture dates back to the 1920s when teachers and students, ladies of prominent families as well as singers, film stars and Chinese opera performers began to wear the dress. In the 1940s, the large number of Shanghai tailors that moved to Hong Kong from the mainland ensured a plentiful supply of cheongsam tailors. With the changes in fashion trends among women in Hong Kong, the cheongsam then became a highly fashionable garment that was in huge demand in the 1950s and 1960s. As the tradition of the cheongsam has been passed down from generation to generation in Hong Kong society, the dress itself has seen a multitude of changes, but it has retained its popularity in the city, where it continues to be worn by many women to important occasions and to provide inspiration to up-and-coming fashion designers.

A Century of Fashion: Hong Kong Cheongsam Story exhibition is not only the opening programme of “Hong Kong Week 2013@Taipei”, it is also the first exhibition brought by our museum to Taiwan. To present this newly curated exhibition to the local audiences, we have come up with this abridged display introducing the transformation that the cheongsam has undergone in Hong Kong from the late Qing dynasty and early Republican period up to the present, while at the same time recounting the development of Hong Kong’s cheongsam industry, the characteristics of cheongsam craftsmanship and fascinating stories of Hong Kong women and their relationship with the cheongsam through different eras.

Posted: February 28th, 2014 | No Comments »

Andrew Field’s Mu Shiying: China’s Lost Modernist is the third book (see Anne Witchard’s Lao She in London and Lindsey Shen’s Knowledge is Pleasure: Florence Ayscough in Shanghai were books 1 & 2) is now available for pre-order on Amazon and will be available in Asia this March. Andrew is also speaking at the Beijing, Shanghai and Suzhou Literary Festivals – details of the book and the China tour below….

When the avant-garde writer Mu Shiying was assassinated in 1940, China lost one of its greatest modernist writers while Shanghai lost its most detailed chronicler of its demi-monde nightlife. As Andrew David Field argues, Mu Shiying advanced modern Chinese writing beyond the vernacular expression of May 4 giants Lu Xun and Lao She to even more starkly reveal the alienation of the cosmopolitan-capitalist city of Shanghai, trapped between the forces of civilization and barbarism. Each of these five short stories focuses on the author’s key obsessions: the pleasurable yet anxiety-ridden social and sexual relationships of the modern city and the decadent maelstrom of consumption and leisure in Shanghai epitomized by the dance hall and the nightclub. This study places his writings squarely within the framework of Shanghai’s social and cultural nightscapes.

SUN MARCH 9, 12 noon to 2 pm @ Bookworm Literary Festival, Beijing Bookworm

WED MARCH 12, 12 noon to 2 pm @ Shanghai Literary Festival, M on the Bund

SUN MARCH 16, 4 pm to 6 pm @ Bookworm Literary Festival, Suzhou Bookworm

THURS APRIL 3, 7 pm to 9 pm @ Wooden Box Cafe, Shanghai

Posted: February 27th, 2014 | No Comments »

He Jiahong, author of Hanging Devils (on amazon.co.uk at a bargain price here), has just published a new Penguin Special and it’s a true crime from the 1990s – Back From the Dead; A Landmark Ruling of Wrongful Conviction in China. Sounds fascinating and he’s doing an event for the Bookworm International Literary Festival this March 2nd – see below

Posted: February 27th, 2014 | 4 Comments »

My thanks to publisher and Hong Kong heritage maven Pete Spurrier (and author of the bestselling Heritage Hiker’s Guide to Hong Kong) for these pictures of Hing Hon Road up in Pokfulam – as it used to look. Having strolled up (sweated and grunted more like!) from Central to Pokfulam to visit Hong Kong University many times I know this area well. Interestingly I recently came across an online pdf (click here) from Kerry Properties (a company that has done much to trash heritage in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing in the last few decades) describing the area around Hing Hon Road as “a timeless neighbourhood”, “tranquil” and with “treasured heritage”. Kerry have helped preserve this timelessness, tranquility and treasured heritage (which includes St. Paul’s College, King’s College and the old quads of HKU) by ripping down the street and putting up two gigantic and ferociously ugly tower blocks called (who knows why) The Summa (see below)! Goodbye sunlight, views, perspectives and heritage. Thanks Kerry. Most of Hing Hon Road was built around 1916 so just failed to make its centenary. A real tragedy.

and now…

Posted: February 26th, 2014 | 12 Comments »

Marjorie Hessell Tiltman was the wife of Hugh Hessell Tiltman, a well known journalist in 1930s China. I covered him briefly in my book Through the Looking Glass, a history of foreign correspodnents in China – ‘Reporting from Manchuria in the early 1930s was not without its hazards. Hessell Tiltman, a British journalist for the London Daily News and three-time president of the Tokyo Foreign Correspondents’ Club, became well known for covering Japan’s latest outposts as its expansionist policy advanced. He was arrested by the Japanese secret police, the Kempeitai, in Manchuria for spying and bizarrely charged with “taking a photograph without a cameraâ€, an accusation neither the journalist nor anyone else seemed to really understand. However absurd a charge, the Japanese were probably right to watch Hessell Tiltman as he probably was a spy, at least part-time. In 1934 he published his take on the Manchurian annexation in association with Colonel P. T. Etherton in their book Manchuria: The Cockpit of Asia. Etherton had been British consul-general in Kashgar between 1918 and 1922 where his major task had been to thwart Bolshevik expansion into either British India or Chinese Turkestan. After that he had been involved in various Balkan machinations before travelling to Manchuria. It is hard to imagine that Hessell Tiltman was not aware of who Etherton was and could not look at the “diplomatic†roles he had undertaken and add two and two together to get “spyâ€.’

Anyway, this post is about his wife, Marjorie. After leaving China it seems the Hessell Tiltman’s settled in West Sussex and Marjorie wrote a delightful book about life in their cottage and village in the late 1930s just before the war, Cottage Pie. I came across a copy the other day while sorting out my father’s book collection – he had no idea how she linked to China. She also wrote on China, including a novel entitled Master Sarah about the opium wars. Still, life in Sussex seemed to please her most…..

Posted: February 25th, 2014 | No Comments »

Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner’s Myths and Legends of China is a classic and now reissued as a kindle. Of course ETC Werner was the diplomat-scholar father of Pamela Werner and features heavily in my book Midnight in Peking. However, I’ve been amazed going round talking about that book at how many older China hands know Werner’s work well and how his book is still seen as a major text in this field, despite being published in the 1920s. Here by all manner of creatures fabulous and mythological and the tales that spawned them – including those pesky fox spirits….

The chief literary sources of Chinese myths are the Li tai shên hsien t’ung chien, in thirty-two volumes, the Shên hsien lieh chuan, in eight volumes, the Fêng shên yen i, in eight volumes, and the Sou shên chi, in ten volumes. In writing the following pages I have translated or paraphrased largely from these works. I have also consulted and at times quoted from the excellent volumes on Chinese Superstitions by Père Henri Doré, comprised in the valuable series Variétés Sinologiques, published by the Catholic Mission Press at Shanghai. The native works contained in the SsŠK’u Ch’üan Shu, one of the few public libraries in Peking, have proved useful for purposes of reference. My heartiest thanks are due to my good friend Mr Mu Hsüeh-hsün, a scholar of wide learning and generous disposition, for having kindly allowed me to use his very large and useful library of Chinese books. The late Dr G.E. Morrison also, until he sold it to a Japanese baron, was good enough to let me consult his extensive collection of foreign works relating to China whenever I wished, but owing to the fact that so very little work has been done in Chinese mythology by Western writers I found it better in dealing with this subject to go direct to the original Chinese texts. I am indebted to Professor H.A. Giles, and to his publishers, Messrs Kelly and Walsh, Shanghai, for permission to reprint from Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio the fox legends given in Chapter XV.