Mortimer Menpes’ Chinois/Japanois London Apartment

Posted: April 1st, 2014 | 1 Comment »Yesterday I posted about the new 3 volume collection of the etchings of Mortimer Menpes. I briefly mentioned his London apartment at 25 Cadogan Gardens (just off Sloane Street, in Knightsbridge) and that it Japanois/Chinois in style and designed by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942), a progressive English architect and designer who influence the Arts and Crafts Movement. Menpes lived in the apartment from the late 1880s to 1900.

In 1899 the magazine, The Studio: an Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art featured Menpes/Mackmurdo’s interiors for 25 Cadogen Gardens. Below that is the exterior of the building from roughly the same time

“The drawing room at 25 Cadogan Gardens, Mr. Mortimer Menpes’ House – The small square wooden tables in the drawing-room are of Chinese form and useful for the reception of ornamental objects”

“The drawing room at 25 Cadogan Gardens, Mr. Mortimer Menpes’ House – The small square wooden tables in the drawing-room are of Chinese form and useful for the reception of ornamental objects”

Luke Him Sau (Lu Qianshou) and Chinese Architecture – April 11, Beijing

Posted: March 31st, 2014 | No Comments »Another event, this time in Beijing, for Ed Denison’s new book on Luke Him Sau:

Lu Qianshou and Chinese Architecture

April 11, 2014 Friday 19:00 – 21:00

- Venue:

- 2F, Rockbund Art Museum (20 Huqiu Road, Shanghai)

- Speaker:

- Edward Denison, Wang Haoyu, Hua Xiahong

- Support:

- Culture And Education Section of The British Consulate-General

This talk examines China’s architectural encounters in the first half of the 20th-century through the lens of one of the country’s most distinguished yet overlooked practitioners: Luke Him Sau (Lu Qianshou, 1904–1991).

Luke is best known internationally and in China as the architect of the iconic Bank of China Headquarters in Shanghai. One of the first Chinese students to be trained at the Architectural Association in London in the late 1920s, Luke’s long, prolific and highly successful career in China and Hong Kong offers unique insights into an extraordinary period of Chinese political turbulence that scuppered the professional prospects and historical recognition of so many of his colleagues.

The story of Luke’s life begins with his childhood in colonial Hong Kong and his apprenticeship with a British architectural firm, before travelling to London to study at the prestigious Architectural Association (1927–30). In London, Luke was offered the post of Head of the Architecture Department at the newly established Bank of China and spent the next seven years in the inimitable city of Shanghai.

From his Shanghai base, he designed buildings all over China for the Bank and other clients before the Japanese invasion in 1937 forced him, and countless others, to flee to the proxy wartime capital of Chongqing. After the war he returned to Shanghai where he formed a partnership with four other Chinese graduates of UK universities; but civil war (between the Communists and Nationalists) once again caused him and others to uproot in 1949.

Initially intent on fleeing with the Nationalists to Taiwan, Luke was almost convinced to stay in Communist China by his friend and fellow architect, Liang Sicheng, but decided finally to move to Hong Kong. There, for the third time in his life, he had to establish his career all over again. Despite many challenges, he eventually prospered, becoming a pioneer in the design of private residences, schools, hospitals, chapels and public housing.

About the speakers

Edward Denison

(architectural historian, writer and photographer) and Guang Yu Ren (architect, researcher and independent consultant) have nearly two decades of international professional experience in architecture and design. They have worked extensively in the UK, China and Africa and authored numerous books based on their projects. These include: Building Shanghai – The Story of China’s Gateway (John Wiley & Sons, 2006), Modernism in China – Architectural Visions and Revolutions (Wiley, 2008), The Life of the British Home – An Architectural History (Wiley, 2012) McMorran & Whitby (RIBA, 2009) and Asmara: Africa’s Secret Modernist City (Merrell, 2003). They are now based in London where Edward is a Research Associate and teaches architectural history and theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London (UCL) and is a teacher at New York University in London.

Hua Xiahong

Associate Professor of Department of Architecture College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University. Phd. in Architectural History and Theory. A main researcher of Hudec Architecture in Mainland China. Author of Shanghai Hudec Architecture in Chinese. Part-time editor of Time Architecture magazine.Â

Published essays: – Modern China’s consuming dream and architecture carnival: since 1992; – Hanging Courtyard The Design Strategy for Blocks B4/B5 of Shanghai Culture & Communication Industry District.

Wang Haoyu

Phd in Architecture, The University of Hong Kong. Research in Modern Chinese Architecture History, Hong Kong Urban Architecture History and Architectural Heritage Protection and Management.

Author of – Architects from Mainland China to Hong Kong after 1949; – Interviewing Mr. Luke Him Sau’s descendants in Hong Kong: A case study of a pioneer modern Chinese architect; and Mainland architects in Hong Kong after 1949: a bifurcated history of modern Chinese architecture.

The Etched Works of Mortimer Menpes 1855-1938

Posted: March 31st, 2014 | 1 Comment »I was first introduced to the Australian/British artist Menpes by Jonathan Wattis, of Wattis Fine Arts in Hong Kong, who had a few of his etchings in stock once when I popped in there. Menpes was an Adelaide boy but studied art in London and was a pupil and flat mate of James McNeill Whistler.

Now, and here’s what interests us all at China Rhyming, he visited Japan in 1887 and was greatly influenced there. He returned to live on London’s Cadogan Square, a flat he decorated in Japanois style (by AH Mackmurdo of the arts and crafts movement). Whistler and Menpes fell out in 1888 over the interior design of the house, which Whistler felt was a brazen copying of his own ideas.

Later in 1902 Menpes headed east again visiting China, Burma and Japan among other places. His sketches and drawings from these trips are wonderful and now available as a three volume set by Gary Morgan – The Etched Works of Mortimer Menpes. I assume, as the books run chronologically that Volume II – covering 1901 to 1913 is the most relevant. Anyway – they’re all here

Regulating Prostitution in China: Gender and Local Statebuilding, 1900-1937

Posted: March 30th, 2014 | No Comments »There is a great existing literature on prostitution in republican China…

There have been some great books on this subject – (think Gail Hershatter’s 1999 Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution and Modernity in Twentieth Century Shanghai is useful for understanding the developing of the city’s brothel business as well as Henriot and Noel Castalino’s Prostitution and Sexuality in Shanghai: A Social History 1849-1949 (2001). Elizabeth Remick’s Regulating Prostitution in China looks like a worthy addition….

In the early decades of the twentieth century, prostitution was one of only a few fates available to women and girls besides wife, servant, or factory worker. At the turn of the century, cities across China began to register, tax, and monitor prostitutes, taking different forms in different cities. Intervention by way of prostitution regulation connected the local state, politics, and gender relations in important new ways. The decisions that local governments made about how to deal with gender, and specifically the thorny issue of prostitution, had concrete and measurable effects on the structures and capacities of the state.

This book examines how the ways in which local government chose to shape the institution of prostitution ended up transforming local states themselves. It begins by looking at the origins of prostitution regulation in Europe and how it spread from there to China via Tokyo. Elizabeth Remick then drills down into the different regulatory approaches of Guangzhou (revenue-intensive), Kunming (coercion-intensive), and Hangzhou (light regulation). In all three cases, there were distinct consequences and implications for statebuilding, some of which made governments bigger and wealthier, some of which weakened and undermined development. This study makes a strong case for why gender needs to be written into the story of statebuilding in China, even though women, generally barred from political life at that time in China, were not visible political actors.

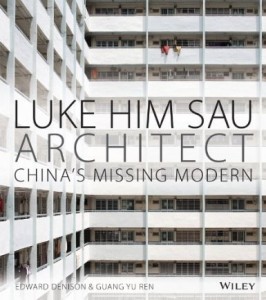

Luke Him Sau, Architect: China’s Missing Modern

Posted: March 29th, 2014 | No Comments »Rediscovering China’s “lost’ modernists is something of a craze at the moment – Lao She rediscovered in 1920s London courtesy of Anne Witchard, Mu Shiying rediscovered in English courtesy of Andrew Field. The more rediscoveries the better I say. And so all hail Edward Denison and Guang Yu Ren for rediscovering Luke Him Sau in a new book. More details on the modernist architect below, plus details of the London launch of the book on April 2nd for all interested….

Luke Him Sau/Lu Qianshou (1904–1991) is best known internationally and in China as the architect of the iconic Bank of China Headquarters in Shanghai. One of the first Chinese students to be trained at the Architectural Association in London in the late 1920s, Luke’s long, prolific and highly successful career in China and Hong Kong offers unique insights into an extraordinary period of Chinese political turbulence that scuppered the professional prospects and historical recognition of so many of his colleagues.

Global interest in China has risen exponentially in recent times, creating an appetite for the country’s history and culture. This book satiates this by providing a highly engaging and visual account of China’s 20th-century architecture through the lens of one of the country’s most distinguished yet overlooked designers. It features over 250 new colour photographs by Edward Denison of Luke’s buildings and original archive material.

The book charts Luke’s life and work, commencing with his childhood in colonial Hong Kong and his apprenticeship with a British architectural firm before focusing on his education at the Architectural Association (1927–30). In London, Luke was offered the post of Head of the Architecture Department at the newly established Bank of China, where IM Pei’s father was a senior figure. Luke spent the next seven years in the inimitable city of Shanghai designing buildings all over China for the Bank before the Japanese invasion in 1937 forced him, and countless others, to flee to the proxy wartime capital of Chongqing. In 1945 he returned to Shanghai where he formed a partnership with four other Chinese graduates of UK universities; but civil war (between the Communists and Nationalists) once again caused him and others to uproot in 1949. Initially intent on fleeing with the Nationalists to Taiwan, Luke was almost convinced to stay in Communist China but decided finally to move to Hong Kong. There, for the third time in his life, he had to establish his career all over again. Despite many challenges, he eventually prospered, becoming a pioneer in the design of private residences, schools, hospitals, chapels and public housing.

The Sinica Podcast – Mark O’Neill on The Chinese Labour Corps

Posted: March 29th, 2014 | No Comments »Following the publication of his Penguin Special on The Chinese Labour Corps Mark O’Neill talks the Coolie Corps and World War One on the excellent Sinica podcast….click here

Just for a Change – A Little Old Bombay

Posted: March 28th, 2014 | No Comments »Just for a change today, a few shots of old Bombay…

Elphinstone Circle remains a marvellous site of old Bombay, and in pretty good nick considering (it helps that some of the shops at ground level have been refurbished with brands like Hermes moving in). The park in the middle of the circle is also still in fairly good working order. The Circle dates back to the 1840s and the park was long a favourite meeting spot for the city’s Parsi community.

Kala Ghoda (which means black horse) was named after the black stone statue of King Edward VII. The statue was a gift from the Sassoon’s around 1870. It’s now housed at the V&A Museum (later renamed the Bhau Daji Lad Museum) in Byculla.

The Bombay Town Hall was built around 1830 and still stands and looks magnificent as an example of Greco-Roman influenced architecture in Bombay and rivals the British Museum building in London for grandeur. It was formerly the home of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bombay and remains in use as a library with 800,000 antique volumes (including, I believe, one of only two original copies of Dante’s Inferno)