Posted: February 12th, 2014 | No Comments »

To commemorate the death of Shirley Temple it seems only fitting that China Rhyming should recall her one celluloid outing to China – Stowaway (1936). Though she didn’t play “yellowface” Shirley was Barbara “Ching Ching” Stewart, a charming orphan stranded in China and originally from Sanchow (no such place, but it sounds kinda Chinesey). When bandits threaten, Ching Ching is taken to Shanghai for safety and meets Tommy Randall, a rich playboy traveling about the world on a ship. Ching Ching accidentally becomes a stowaway on his ship.

Apparently Temple learnt 40 words of Chinese to play the part, which, she later claimed, took her six months!! Trivia fans may like to know that after the film wrapped Temple was given the Pekingese dog that had played her character’s pet dog, “Mr. Woo.” Temple renamed the dog “Ching-Ching,” after her character in the movie. Sweet!

Posted: February 11th, 2014 | 3 Comments »

Today I’ll just point you to Stuart Heaver’s great story of the German battleship SMS Emden and Hong Kong during the First World War in 1914 from the South China Morning Post…a fascinating read….As I knew nothing about this, I’ll (for once) add nothing!

Posted: February 10th, 2014 | No Comments »

The 8-9th February was the 110th anniversary of the Battle of Port Arthur (Lushun) in 1904 – the commencement of the Russo-Japanese War. It began with a surprise night attack by a squadron of Japanese destroyers on the Russian fleet with skirmishing off Port Arthur continuing until May 1904.

Â

Here’s a Japanese print of the Russian navy taking a pasting…

Posted: February 9th, 2014 | No Comments »

A quick post to note that one of the best selling books in the Zed Asian Arguments series (which I commission and edit), Tom Miller’s China’s Urban Billion, has now been launched in a Chinese edition in Taiwan (online here from Eslite and all good bookshops in the ROC)….

Posted: February 8th, 2014 | No Comments »

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China

CALL FOR ARTICLES

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China publishes original research articles of up to 10,000 words (shorter articles are also welcome) on Chinese culture and society, past and present, with a focus on mainland China. Original articles, which will be peer-reviewed, must be previously unpublished, and make a contribution to the field. The Journal also publishes timely reviews of books on all aspects of Chinese history, culture and society.

The deadline for submission is April 30, 2014.

All material should be submitted as an electronic attachment to the editor. A separate cover sheet should include the following:

§ Title of work

§ Contributor’s name and contact information § Abstract of up to 300 words

For peer review, the main body of the text should not include the author’s name. Text should be double-spaced, left-aligned, 12pt, in an easily read font such as Times New Roman, and paginated. The first line of paragraphs should be indented.

Illustrations should be high quality JPEG or TIFF files, and able to reproduce well in black and white. Authors are responsible for securing copyright permissions, and for any associated costs.

Submissions will be acknowledged by e-mail. Original articles that in the opinion of the editor make a significant contribution to the field will be sent to one independent peer reviewer. The Journal operates a “double-blind” system of review which means that neither the reviewer nor the writer is informed of the other’s identity. Following peer review, an article may be accepted, accepted with revisions, or declined. Authors of accepted original articles will be sent a proof before publication. This is for final checking only, as no substantial revisions are possible at this stage.

The journal uses British English. For punctuation, vocabulary and Romanization of Chinese, please refer to the Hong Kong University Press Style Manual.

Notes should appear at the end of the article, and be formatted according to The Chicago Manual of Style. The notes and bibliography system, or the author-date system may be used according to whether your paper falls into the category of humanities, or physical/social sciences. A quick guide is available at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html.

For archival sources, please follow the format requested by the repository.

Enquiries may be sent to the Honorary Journal Editor, Dr. Neil Schmid – editor@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China is a continuation of the original scholarly publication of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, the Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, published from 1858 to 1948. The Journal proudly maintains the level of academic standards and innovative research that marked its standing as the preeminent Western sinological journal in China for nearly a hundred years.

Posted: February 7th, 2014 | 2 Comments »

Took a trip out to the old WW2 codebreakers haunt at Bletchley Park the other day. The story of Bletchley, the big brains there and the Enigma codes is well known and, of course, the old Bletchley days have been in the news recently with the long awaited and well deserved Royal pardon for Alan Turing, the maths and computer genius, hounded for his homosexuality after WW2 until he eventually committed suicide. It’s worth also I think remembering two great Asia Hands who worked at Bletchley which also worked, successfully, on cracking Japanese codes as well as German during the war.

Hugh Foss (above) was a major figure at Bletchley. He had the good fortune to be born in Kobe, Japan, the son of a British missionary bishop. His Japanese was excellent and followed by a good old English public school education and a stint at Cambridge. Foss joined the Government Code and Cipher School in the 1920s and worked on cracking the Enigma codes but it was his Japanese skills that lead in large part to the breakthroughs that cracked the Japanese Naval Attache ciphers in 1940 and saved so many British and American lives during the war in the Pacific. Between 1942 and 1943 Foss headed up the Japanese section at Bletchley and later moved to Washington to share his knowledge and help the American codebreakers delve deeper into the Japanese naval codes. As a true Bletchley eccentric, Foss always wore sandals and became known in America as the “Lend-Lease Jesus”.

A close colleague of Foss’s on the Japanese codes was Oliver Strachey (above), brother of the writer Lytton Strachey. At Oxford he became something of an Asia Hand writing part of the great history of Bombay published in 1916. Strachey too joined the Government Code and Cipher School in the 1920s where he worked with Foss on cracking Japanese codes, as early as 1934. Stachey also later moved to Washington to share expertise on both Japanese and Vichy French codes with the Americans. Amazingly, and unlike Foss, Strachey didn’t speak Japanese – amazing as cracking their codes regarded a high level of familiarity with variations of kanji, hiragana, and romanization.

And finally, a history of the prominent Asia Hands at Bletchley during the War should also include John”The Brig” Tiltman, a great cryptographer who had also previously worked for the Government Code and Cipher School in the 1920s where he cracked codes for the British Army Headquarters in Simla allowing them to read Russian diplomatic cypher traffic from Moscow to Kabul, Afghanistan and Tashkent, Turkestan. At Bletchley Tiltman was deeply involved in cracking the Japanese codes too.

Three amazing Asia Hands who saved thousands of lives and shortened the war through their work and Asian knowledge. If I’ve missed any major Asia Hands who were active cryptographers or code breakers at Bletchley then please do let me know…..And for a lot, lot more on this subject do look out for Michael Smith’s The Emperor’s Codes: Bletchley Park’s Role in Breaking Japan’s Secret Cyphers.

the Mansion at Bletchley Park today – go visit…

Posted: February 6th, 2014 | No Comments »

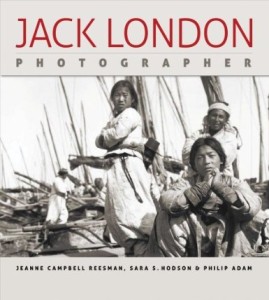

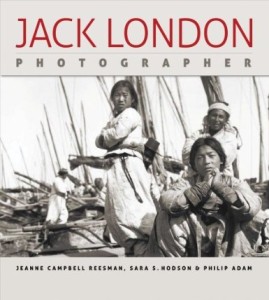

Following yesterday’s post noting Jack London’s presence as a reporter at the Russo-Japanese War (which surprised some) I would recommend this excellent collection of his photography which includes a lengthy section of his shots from that war….

Posted: February 5th, 2014 | 2 Comments »

Following on from yesterday’s post on foreign journalistic coverage of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, another excerpt from my book, Through the Looking Glass, on the role of photography during the war, another reason the generals of 1914-1918 shouldn’t have been so surprised by events during WW1.

Photography and the Russo-Japanese War

Jack London with Japanese Officers in Korea during the Russo-Japanese War

Jack London with Japanese Officers in Korea during the Russo-Japanese War

As it was for modern warfare, the Russo-Japanese War was revolutionary for modern photography. While stereoscopic slides had been about during the Boxer Rebellion and the Spanish-American War, the Russo-Japanese War was perhaps their major introduction to mass appeal. Arguably the strongest images of the war came from the Russian “Photographer to the Czar†Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii. He was both the official photographer for the Russian side on the Manchurian battlefield and for the Trans-Siberian Railway project.

The war was photographed in graphic style — which showed clearly that by 1905 editors understood the value of gory pictures — with images of Shenyang and Port Arthur sent around the world. Self-taught photographing brothers Elmer and Bert Underwood produced box sets of stereographs from the war, including a striking shot of Japanese soldiers carrying out an execution. Jack London and James Ricalton sent photographs, which demonstrated that war correspondents were now sending images as well as text and pioneering photojournalism in China. Ricalton sent back amazing shots for the time and was given virtually unparalleled access for a foreigner to the Japanese forces. Herbert Ponting, an Englishman who had emigrated to America in his early twenties, went to the war as Harper’s Weekly’s correspondent and later returned to travel around Japan, India, China, Korea, Java and Burma. He too sent back pictures as well as text. Ponting was later the official photographer on Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition.

An Underwood and Underwood picture of a Japanese trench

An Underwood and Underwood picture of a Japanese trench

The Russo-Japanese War was also the first time spies posing as journalists used photography. Some were found to be smuggling secret reports in micro-photographic form and the war provided evidence of the increasingly shady links between journalism and espionage. The Russians later revealed that they had obtained information on Japan’s strategy, including the plan for the major offensive in Manchuria in March 1905 that Jack London witnessed, through a Tokyo-based French correspondent, a Monsieur Balais of Le Figaro. Through the mysterious Frenchman, Russia found out in August 1904 that Japan would attack Shenyang, which was under Russian control at the time, as early as January 1905. Alexander Pavlov, a senior Russian diplomat in Korea, had apparently hired Balais who had begun his espionage career in Shanghai a couple of years earlier. Balais sent around 30 reports to Pavlov in Shanghai by regular sea mail.

A James Ricalton “stereo card” of Tsarist and Japanese troops

Film cameras were also in evidence now too. George Roberts filmed the Russian army marching from Siberia to Manchuria, securing notable images showing the beheading of a Chinese bandit, while Joseph Rosenthal filmed on the Japanese side for the Charles Urban Trading Company. Rosenthal had already filmed the Boer War, travelling with Lord Roberts’s column, as well as the American occupation of the Philippines. At the same time, correspondents also did deals with local photographers, even buying pictures from the photographic unit of the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters and from Japanese photographers such as Koson Ohara who produced prints similar to those that had proved popular during the earlier Sino-Japanese War.

After 1905, wherever foreign journalists were to be found in China, photographers would also be constantly present, and shortly after that newsreel cameramen also. The China story was now to be one of text and images together.

An Underwood and Underwood image of the Siege of Port Arthur (Lushun)