Posted: November 24th, 2013 | No Comments »

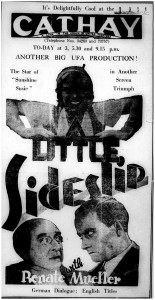

Many China Rhymers will know and love the Cathay Cinema on Avenue Joffre (Huai Hai Middle Road), one of the loveliest of Shanghai’s remaining pre-war movie houses (and still an active cinema). What I did not know was that as well as British and American films the cinema also screened big German movies from the famous UFA studios and with English subtitles (and air-con). Here is the poster for the 1934 screening of Little Sideslip. A small mystery – I am not sure which of the star Renate Mueller’s movies for UFA this actually was as the English title for the film is a little difficult to match to any of her movies and isn’t listed anywhere I know of under this title – any ideas welcome?

Mueller was a massive UFA star in the 1920s, right up there with Dietrich, though, unlike Marlene, she remained in Germany and died (under what some think was highly suspicious circumstances) shortly after leaving in hospital in 1937 for a knee operation (or possibly to try and cure drug addiction).

Posted: November 23rd, 2013 | No Comments »

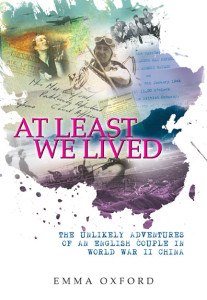

An interesting new book is now out – At Least We Lived (book’s website here with some old photos of China too) by Emma Oxford….details below

At Least We Lived is the remarkable story of Max and Audrey Oxford, a British couple who met and married in China at the height of the Second World War. Their tales — including Max’s Christmas Day escape from Hong Kong under fire from the Japanese, and the eight-week journey Audrey embarked on alone that would take her thousands of miles from her family — are reminders of a time and place far removed from the technologies and speed of modern life.  Written by their daughter Emma, the book expertly weaves together Max and Audrey’s personal stories with the history of China and how World War II shaped the region and those in it.

Posted: November 22nd, 2013 | No Comments »

Not sure there are enough parasols, even if there are too many lanterns these days, on book covers….R. Clifton Spargo’s Beautiful Fools: the Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald has a lovely Chinoiserie parasol on the cover. Of course Chinese parasols were a great delight of the Jazz Age, but Zelda did have an interest in China it seems. Though overshadowed by her husband, Zelda was also a writer and one of her short stories The Girl With Talent (or sometimes The Girl Who Had Some Talent) did feature a flapper dancer in 1920s New York who is offered a career chance of a lifetime but opts instead to elope with her lover to China. The story is a tad tricky to find these days – it appeared in the rather obscure (now at least) College Humor in April 1930. I believe it is in some of the out-of-print collections of Zelda’s shorter fiction.

1929/1930 were of course difficult years for Zelda – in 1930 she was admitted to a sanatorium in Maryland diagnosed bipolar and her marriage was failing. Running away to China must have seemed like a good idea at the time one can imagine.

Posted: November 21st, 2013 | No Comments »

I’ve posted rather a lot on Chinese lanterns and their role as a symbol of the Jazz Age and Chinoiserie in Western literature (here, here, here and here). Nice to see then that contemporary authors seeking to recreate the rather louche environs of history (in this case just post-war privileged America) use Chinese lanterns in their work to evoke the era and mood.

This from the recent best seller, Liza Klaussman’s Tigers in Red Weather (details below)…..

‘As the party drew near, Nick seemed to get lost in the minutiae of Chinese lanterns and silver polish…’

“Nick and her cousin Helena have grown up together, sharing long hot summers at Tiger House. With husbands and children of their own, they keep returning. But against a background of parties, cocktails, moonlight and jazz, how long can perfection last? There is always the summer that changes everything”

Posted: November 18th, 2013 | No Comments »

I know nothing about the Remarkable Chester Ronning so this new book by Brian Evans may shed some light…..

Scholar and diplomat Brian L Evans gives us the first English-language biography of Chester A Ronning (1894-1984): diplomat, politician, educator, and one of Canadas major public figures. This fascinating story depicts Ronning, the man who received many honours, and deepens readers’ knowledge of Canadas post-World War II diplomacy and Canada — China relations. Ronning was a extraordinary Canadian who combined Chinese sensibility with Norwegian calm practicality and American drive. His life journey was entwined with the history of China over many decades. Based on written materials, historical documents, and many hours of interviews with Ronning, his friends, and fellow politicians, The Remarkable Chester Ronning offers both a thorough and entertaining biography and a lens through which to view international politics.

Posted: November 16th, 2013 | No Comments »

Among the numerous Chinese magicians (both real Chinese and fake with yellow greasepaint, black wigs and meaningless imitation pidgin English) to impress European and American audiences over the centuries, none was more popular than Ching Ling Foo (1854-1922), real name Chee Ling Qua, who had been born in Peking and was a respected performer in China before bringing his show to America in 1898. Dressed in typical late Qing-era garb he breathed smoke and fire over audiences, producing ribbons and a fifteen foot long pole from his mouth to their amazement and beheaded a boy who then, to the amazement of the audience, walked off the stage sans head. His show stopper involved producing a huge bowl, full to the brim with water, from out of an empty cloth. He would then pull a small child from the bowl. Other magicians were in awe of Ching Ling Foo. He travelled the States with his bound footed wife and a retinue of Chinese women who were as much an attraction as his magic. His fame was such that he got a mention in Irving Berlin s 1917 song From Here to Shanghai. He had a host of imitators, not least Chung Ling Soo, who I’ve blogged about repeatedly here and here.

And so here’s Irving Berlin’s lyrics immortalising Ching Ling Foo….

The sheet music cover

The sheet music cover

And the “78” itself

“From Here To Shanghai”

I’ve often wandered down

To dreamy Chinatown

The home of Ching-a-ling

It’s fine! I must declare

But now I’m going where

I can see the real, real thing

I’ll soon be there

In a bamboo chair

For I’ve got my fare

From here to Shanghai

Just picture me

Sipping Oo-long tea

Served by a Chinaman

Who speaks a-way up high

(“Hock-a-my, Hock-a-my”)

I’ll eat the way they do

With a pair of wooden sticks

And I’ll have Ching Ling Foo

Doing all his magic tricks

I’ll get my mail

From a pale pig-tail

For I mean to sail

From here to Shanghai

I’ll have them teaching me

To speak their language, gee!

When I can talk Chinese

I’ll come home on the run

Then have a barr’ll of fun

Calling people what I please

(you can hear it here on a rather charming youtube clip)

Ching Ling Foo himself

Posted: November 15th, 2013 | No Comments »

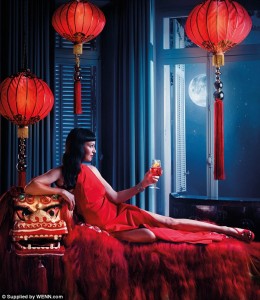

Campari’s 2014 calendar features Uma Thurman in a variety of settings and national holidays with the obligatory glass of Campari in each. I thought China Rhymers might like to see Uma doing Spring Festival in Beijing in high Chinoiserie style….And my point is?….Well, there isn’t one really but this is the only blog that will focus on the symbolism of the Chinese lanterns in the photo I can assure you!!

Posted: November 14th, 2013 | No Comments »

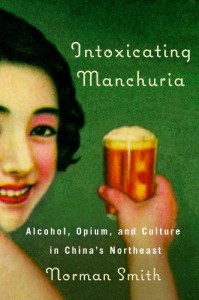

Norman Smith’s Intoxicating Manchuria looks interesting….

In China, both opium and alcohol were used for centuries in the pursuit of health and leisure while simultaneously linked to personal and social decline. The impact of these substances is undeniable, and the role they have played in Chinese social, cultural, and economic history is extremely complex.

In Intoxicating Manchuria, Norman Smith reveals how huge intoxicant industries were altered by warlord rule, Japanese occupation, and war. Powering the spread of alcohol and opium — initially heralded as markers of class or modernity and whose use was well documented — these industries flourished throughout the early twentieth century even as a vigorous anti-intoxicant movement raged.

This book provides a detailed analysis of the media’s positive and negative portrayals of alcohol in the 1930s and 40s, which includes the advertising industry’s promotion of alcohol and its subsequent calls for prohibition. While tracing the history of opium and alcohol consumption in China and the business of intoxicant production in Manchuria, Smith highlights the efforts of anti-intoxicant activists, scientists, bureaucrats, and writers to raise awareness of the dangers of intoxicants. This is the first English-language book-length study to focus on alcohol use in modern China and the first dealing with intoxicant restriction in the region.

Norman Smith is an associate professor in the History Department of the University of Guelph. He is the author of Resisting Manchukuo: Chinese Women Writers and the Japanese Occupation and co-editor of Beyond Suffering: Recounting War in Modern China.