Posted: January 26th, 2014 | No Comments »

I’ve posted about Timothy Brook’s book Mr Selden’s Map of China last year but I note that the Economist reviewed it alongside this book, on London, the Selden map and the making of a global city via, in part, the China trade, from Robert Batchelor – so I’m also noting it….

If one had looked for a potential global city in Europe in the 1540s, the most likely candidate would have been Antwerp, which had emerged as the center of the German and Spanish silver exchange as well as the Portuguese spice and Spanish sugar trades. It almost certainly would not have been London, an unassuming hub of the wool and cloth trade with a population of around 75,000, still trying to recover from the onslaught of the Black Plague. But by 1700 London’s population had reached a staggering 575,000—and it had developed its first global corporations, as well as relationships with non-European societies outside the Mediterranean. What happened in the span of a century and half? And how exactly did London transform itself into a global city?

Â

London’s success, Robert K. Batchelor argues, lies not just with the well-documented rise of Atlantic settlements, markets, and economies. Using his discovery of a network of Chinese merchant shipping routes on John Selden’s map of China as his jumping-off point, Batchelor reveals how London also flourished because of its many encounters, engagements, and exchanges with East Asian trading cities. Translation plays a key role in Batchelor’s study—translation not just of books, manuscripts, and maps, but also of meaning and knowledge across cultures—and Batchelor demonstrates how translation helped London understand and adapt to global economic conditions. Looking outward at London’s global negotiations, Batchelor traces the development of its knowledge networks back to a number of foreign sources and credits particular interactions with England’s eventual political and economic autonomy from church and King.Â

Â

London offers a much-needed non-Eurocentric history of London, first by bringing to light and then by synthesizing the many external factors and pieces of evidence that contributed to its rise as a global city. It will appeal to students and scholars interested in the cultural politics of translation, the relationship between merchants and sovereigns, and the cultural and historical geography of Britain and Asia.

Posted: January 25th, 2014 | No Comments »

This year we can obviously expect to hear a lot about the First World War. We’ll also be hearing something about the Chinese involvement in the European war through the men of the Chinese Labour Corps (the CLC or “Coolie Corps”), the Chinese recruited to help with logistics and clearing the battlefields by the British and French. I’ve blogged on the Coolie Corps before (here, here, here and here). I’ve also blogged about friend and veteran China hack Mark O’Neill who’s grandfather was a missionary in China and worked with the CLC – Mark has a short book on the CLC out this spring (more on that nearer the time).

Inevitably some of the Chinese men died at the Front and needed to be buried and then remembered after the war. The passage below is from the notes advising on how the graves of Chinese should be placed and handled in France issued in 1918. It comes from the superb and beautifully written history of the War Graves Commission and the man behind it Fabian Ware, Empire of the Dead: How One Man’s Vision Led to the Creation of WW1’s War Graves, by David Crane. I can’t recommend this book highly enough.

the way to bury the Chinese ideally,

“is on sloping ground with a stream below, or gully down which water always or occasionally passes. The grave should not be parallel to the north, south, east or west. This is especially important to Chinese Mohammedans. It should be about 4ft deep, with the head towards the hill and the feet towards the water. A mound of earth about 2ft high is piled over the grave…Whenever possible the friends of the deceased should be allowed access to the corpse, and should be allowed to handle it, as they like to dress it and show marks of respect.”

Posted: January 24th, 2014 | No Comments »

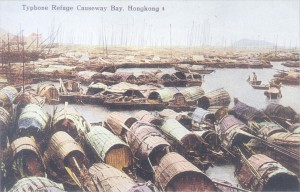

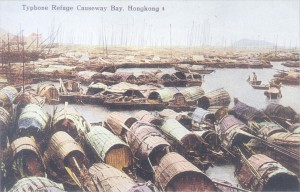

Sampans battened down for an incoming typhoon in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong….sorry – don’t have a date for this card

Posted: January 23rd, 2014 | No Comments »

I intend to get some more posts out of the 30th anniversary this year of the first publication of JG Ballard’s Empire of the Sun, but today, a selection of covers over the past three decades….

Posted: January 22nd, 2014 | 1 Comment »

Don’t often stick up pictures of cancelled postage but thought I’d offer this 1948 stamps, some of the last from the REpublic of China, featuring Sun Yat-sen and a nice contrast of old time junk and new fangled aeroplane. The issuing value of the stamps gives some idea of the crazy rates of inflation at the time. And that’s all my knowledge on stamps!

Posted: January 21st, 2014 | No Comments »

David Finkelstein’s Washington’s Taiwan Dilemma looks interesting…..

The declaration of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949 presented American foreign policy officials with two dilemmas: How to deal with the communist government on the mainland and what to do about Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist regime on Taiwan. By 1950, these questions were pressing hard upon U.S. civilian and military planners and policy makers, for it appeared that the Red Army was preparing to invade the island. Most observers believed that nothing short of American military intervention would preclude a communist victory. How U.S. officials grappled with the question of what to do about Taiwan is at the heart of “Washington’s Taiwan Dilemma” Today, U.S. policy toward Taiwan remains a highly-charged and fundamentally divisive issue in U.S.-China relations–especially the security dimensions of that policy. This volume is essential background reading for understanding the roots of this foreign policy dilemma.

Posted: January 17th, 2014 | No Comments »

Here today (a rather busy weekend ahead) simply a postcard of Shanghai “Harbour” taken around 1905 and posted in 1907

Posted: January 16th, 2014 | No Comments »

I came across a quirky little post the other day on the China Car Times blog concerning Chinese wheelbarrows. Chinese one wheeled wheelbarrows are indeed different from western style barrows. However, that reminded me of the drawings of Chinese wheelbarrows with sails and then John Milton.

Blind John Milton (1608-74) was born into the height of the Protestant Reformation in England. He clearly found what little news came from China interesting and wrote “Chinese drive, with sails and wind, their cany waggons light” in Paradise Lost (1667) indicating that the West knew of the sail driven wheelbarrows of China that William Alexander was to paint over a century later (below) in the 1790s when he saw them while accompanying Lord McCartney s Mission to China. Milton also noted the spice trade as well as the greatness of Beijing in Paradise Lost:

“City of old or modern fame, the seat

Of mightiest empire, from the destined walls

Of Cambalu, seat of Cathaian Can”

Milton later refers to Pequin without apparently realising that both Pequin and Cambalu are alternative names for Beijing. It seems Milton was excited by China as a vast market for English manufacturing but criticised what he saw as the country s absolutist government which, in his mind, paralleled the absolutism of Catholicism and the Divine Right of Kings.

Â