Posted: March 14th, 2014 | No Comments »

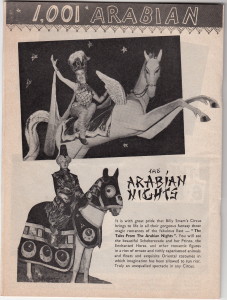

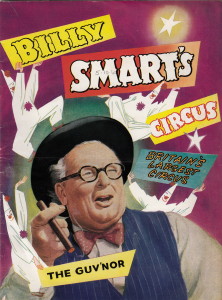

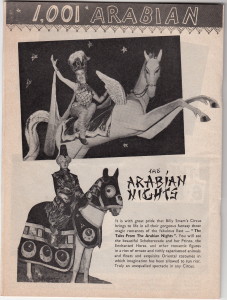

There was a time when if you went to the circus in England (and I mean a proper circus with animals and everything) it was probably Billy Smart’s. He ran carnivals, funfairs and circus’s since the 1930s. In 1960 they came to town (London’s Alexandra Palace to be exact) with a new show featuring Orientalism galore and 1,001 Arabian Nights….

Posted: March 13th, 2014 | No Comments »

Raffles in 1920….

Posted: March 12th, 2014 | No Comments »

A bit more modern for this blog but Austin Jersild’s The Sino-Soviet Alliance looks interesting and some fun graphics from the period….

In 1950 the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China signed a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance to foster cultural and technological cooperation between the Soviet bloc and the PRC. While this treaty was intended as a break with the colonial past, Austin Jersild argues that the alliance ultimately failed because the enduring problem of Russian imperialism led to Chinese frustration with the Soviets.

In 1950 the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China signed a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance to foster cultural and technological cooperation between the Soviet bloc and the PRC. While this treaty was intended as a break with the colonial past, Austin Jersild argues that the alliance ultimately failed because the enduring problem of Russian imperialism led to Chinese frustration with the Soviets.

Jersild zeros in on the ground-level experiences of the socialist bloc advisers in China, who were involved in everything from the development of university curricula, the exploration for oil, and railway construction to piano lessons. Their goal was to reproduce a Chinese administrative elite in their own image that could serve as a valuable ally in the Soviet bloc’s struggle against the United States. Interestingly, the USSR’s allies in Central Europe were as frustrated by the “great power chauvinism” of the Soviet Union as was China. By exposing this aspect of the story, Jersild shows how the alliance, and finally the split, had a true international dimension.

Posted: March 12th, 2014 | No Comments »

About a year ago I blogged about reading Jean Rhys’s earlier works and how she describes (fictionally – but all her fiction was drawn from her early, rather vagabond, life) going for a Chinese meal in Paris in the early 1930s. Just so happens I recently read her another of her earlier works, Quaret, a fictionalised account of her 1920s affair with Ford Madox Ford in Paris. So it seems she went for a Chinese earlier, in the 1920s…I’m not sure there’s a Chinese restaurant where she describes there now, or even was in the 1920s, but she tells of the Restaurant Chinois on Rue de L’ecole de Medicine. The street is in the Odeon quarter of the sixth arrondissement. It’s close to the Sorbonne in the Latin Quarter and so, not surprisingly, Rhys describes moving upstairs from the restaurant after dinner to,

“the red-lit bar where several Chinese students were dancing with very blonde women long past their first youth. The students strutted past in a stiffly correct way, melancholy for the sake of dignity, but obviously highly pleaseed with themselves. At intervals the lights were lowered and a good-looking young violinist played sentimental music on muted strings, and occasionally the something-or-other girls, four of them, pranced in and did a few acrobatics in strict time.’

A late nineteenth century view of the area around Rue de L’ecole de Medicine

Posted: March 11th, 2014 | 1 Comment »

Following yesterday’s Rangoon skyline view, another postcard. I’m not quite sure the date of this postcard but suspect it’s from the early years of the twentieth century as Rangoon’s General Hospital (now the Yangon General Hospital) was completed in 1899 and finally opened for business in 1905. The hospital was expanded somewhat after World War Two and had new wings added in the mid-sixties.

and the hospital today…

Posted: March 10th, 2014 | 1 Comment »

Today a postcard of Rangoon’s skyline in the late nineteenth century….

Posted: March 10th, 2014 | No Comments »

A nice new reissue of Hosie’s Three Years in Western China on Kindle.…

The following pages are intended to present a picture of Western China as the writer saw it in 1882, 1883, and 1884. Chapter VII., in a somewhat modified form, was read at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on the 22nd of February, and published in the Proceedings for June, 1886; Chapter XI. was read at the Aberdeen meeting of the British Association in September, 1885; and Chapter XII. was addressed to a special meeting of the Manchester Chamber of Commerce on the 12th of May, 1886. The remaining Chapters are now published for the first time, and, if they meet with half the favour bestowed upon the Parliamentary Papers in which the journeys were first, and somewhat roughly, described, the writer will consider himself amply rewarded for the work which want of leisure has compelled him to neglect so long.

The Author.

Wênchow, China,

September 6, 1889.

Posted: March 8th, 2014 | No Comments »

Penguin China have commissioned a bunch of writers to think about the issues involving China and the First World War. In this centenary year there’s bound to be a flood of books, TV, movies on WW1 but China’s involvement in the conflict and the effects of that war on the fledgling republic and its people are generally poorly covered. So a series that adds something different to perspectives on both the Great War and China’s history. All are available as e-books with paperbacks available in Asia and Australia.

There’s a whole bunch of great authors involved including Jonathan Fenby, Mark O’Neill, Anne Witchard, Frances Wood, Robert Bickers and myself (my own contribution on China at the Paris Peace Conference and the ramifications of China’s betrayal by the Great Powers at Versailles is out in the spring).

The series is now launched with Jonathan Fenby’s The Siege of Tsingtao, the only battle of WW1 to be fought in East Asia with the Japanese seizure of the German possessions in Shantung (Shandong). Jonathan will taking about the book and the Siege at the Beijing International Literary Festival on the 14th March (click here)

Also up and out now is Mark O’Neill’s The Chinese Labour Corps, the story of the thousands of Chinese men recruited by the British and French to provide logistical support and clean the battlefields in Europe. It’s a fascinating story and little known outside China history buffs (I’ve blogged on it here, here and here).

Mark will also be speaking at the Beijing festival (March 9th) on China and WW1 with Paul Ham (author of 1913: The Eve of War) and Steven Schwankert (author of Poseidon: China’s Secret Salvage of Britain’s Lost Submarine)