Posted: October 16th, 2013 | No Comments »

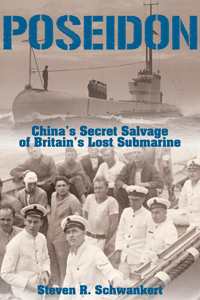

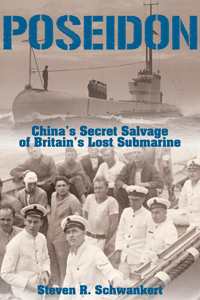

I’ve posted before on the story of HMS Poseidon and its sinking off the China coast in 1931. Excellent to see Steven Schwankert’s long awaited book on both the sinking, the sub, the men who crewed her and his hunt for the wreck and any trace of her in China is now out. More details and an interview with the author here from the WSJ‘s China Real Time Report…

Poseidon: China’s Secret Salvage of Britain’s Lost Submarine

Steven R. Schwankert

Royal Navy submarine HMS Poseidon sank in collision with a freighter during routine exercises in 1931 off the Chinese coast. Thirty of its fifty-six-man crew scrambled out of the hatches as it went down. Of the twenty-six who remained inside, eight attempted to surface using an early form of diving equipment: five of them made it safely to the surface in the first escape of this kind in submarine history and became heroes. The incident was then forgotten, eclipsed by the greater drama that followed in World War II, until news emerged that, for obscure reasons, the Chinese government had salvaged the wrecked submarine in 1972. This lively account of the Poseidon incident tells the story of the accident and its aftermath, and of the author’s own quest to discover the shipwreck and its hidden history.

Steven R. Schwankert is an editor and award-winning reporter with seventeen years of experience in Greater China. He is the Asia chapter chair of The Explorers Club, a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and founder of SinoScuba, Beijing’s first professional scuba-diving operator. In 2007, he led the first ever scientific expedition to dive Mongolia’s Lake Khovsgol. He regularly guides divers to the Underwater Great Wall and a Ming-dynasty city that lies beneath a lake in China’s Zhejiang Province.

“Schwankert’s tale of a lost submarine, its discovery and secret salvage by the Chinese is a compelling, real-life exposé. Exciting, suspenseful, filled with intrigue, Poseidon is a must-read to set lost history on the track to truth.â€

—Clive Cussler, author of Raise the Titanic and Poseidon’s Arrow

“Poseidon is an excellent account of a fascinating episode in naval history. I highly recommend this superb book.â€

—Alex Kershaw, author of Escape from the Deep and The Liberator

“Poseidon is the gripping story of the dramatic final moments of a British submarine—the survivors’ compelling story and the awful fate of those trapped inside. But Poseidon is also the story of Schwankert’s dogged quest and maritime detective work to uncover the truth on that dreadful day in Royal Navy history.â€

—Paul French, author of Midnight in Peking

Posted: October 15th, 2013 | No Comments »

I just finished a swift book tour through the Mid-West and New York and found myself walking through New York’s Chinatown. As it happened I’d brought along a copy of Your United States: Impressions of a First Visit, a series of vignettes written by the English writer Arnold Bennett, penned while he was on a book tour of the States roughly a century ago, in 1912. It’s a slim but entertaining volume with some funny observations on American hotels, restaurants, sports and telephone obsessions. Bennett too visited Chinatown…it was then, as now, a major tourist attraction….

“We even saw Chinatown, and the wagonettes of tourists stationary in its streets. I had suspected that Chinatown was largely a show for tourists. When I asked how it existed, I was told that the two thousand Chinese of Chinatown lived on the ten thousand Chinese who came into from all quarters on Sundays, and I understood. As a show it lacked convincingness – except the delicatessen-shop, whose sights and odors silenced criticism. It had the further disadvantage, by reason of its tawdry appeals of color and light, of making one feel like a tourist…

And it was a proud moment when in an inconceivable retreat we were permitted to talk with an aged Chinese actor and view his collection of flowery hats. It was a still prouder (and also a subtly humiliating) moment when we were led through courtyards and beheld in their cloistral aloofness the American legitimate wives of wealthy Chinamen, sitting gorgeous, with the quiescence of odalisques, in gorgeous uncurtained interiors. I was glad when one of the ladies defied the detective (guiding Bennett through Chinatown) by abruptly swishing down her blind.”

Posted: October 14th, 2013 | No Comments »

The folk at the Los Angeles Review of Books thought it a good idea to have a look at issues around Chinese literature, the Nobel Prize and various reputations. I have to admit an interest as I contributed an essay on Lao She (who never won and probably wasn’t that bothered about it), Untidy Endings.

There’s also Julia Lovell on Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, Brendan O’Kane on Qian Zhongshu’s Fortress Besieged and Charles W. Hayford on Pearl S. Buck.

All worth a read…

Posted: October 13th, 2013 | 1 Comment »

Really shoehorning here but as I was in St Louis, home town of TS Eliot, I thought I’d see if he had any Chinese references I’d overlooked before. Of course Eliot was generally complimentary of Ezra Pound’s Chinese poetry translations declaring him the “inventor” of Chinese poetry as we know it today (today being 1928). However, this is the only slight reference I could find to aything Chinese in Eliot…in fact to a Chinese jar from his Four Quartets from the 1940s:

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness

Not the stillness of the violin, while the note lasts

Not that only, but the co-existence

Or say that the end precedes the beginning

And the end and the beginning were always there

Before the beginning and after the end

And all is always now. Words strain

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish

Will not stay still. Shrieking voices

Scolding, mocking, or merely chattering

Always assail them. The Word in the desert

Is most attacked by voices of temptation

The crying shadow in the funeral dance

The loud lament of the disconsolate chimera

Posted: October 13th, 2013 | No Comments »

UK readers may be interested in the new Sunday Mirror Book Club which gives you free books!! Including Midnight in Peking in some rather illustrious company…should be more details in this Sunday’s paper…..

Posted: October 12th, 2013 | No Comments »

As part of the ongoing Isamu Noguchi-Qi Baishi-Beijing 1930 exhibition at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City I’ll be talking about the city Noguchi encountered when he arrived….

Paul French | Peking 1930 – Isamu Noguchi and his Encounter with China’s Cultural Capital and Avant Garde Milieu

Sunday, October 13, 2013 – 3:00pm – 4:00pm

When Isamu Noguchi arrived in Peking for the first time in June 1930 he declared “Peking is like Paris.” In China Noguchi was continuing his journey to being a World Citizen and influential Modernist artist. Previously, in New York, Paris and London, Noguchi had learned to appreciate “the value of the moment,” but also became interested in Asian art forms and styles. As a committed Modernist he explicitly rejected the ideology of Realism and in doing so he sought to make use of the artistic styles of ancient traditions. In China he was to study under Qi Baishi, the classical water colorist, calligrapher and woodcutter.

However, Noguchi’s sojourn in Peking came at a time of intense political upheaval in the former Chinese capital. On the eve of the Japanese annexation of Manchuria, Peking was in thrall to rampant warlordism. It was a city on the edge- both in terms of its proximity to Japanese incursions in the north, and rising fears among the city’s population for their future political stability. Peking was a place of vast contrasts- both ancient and modern, imperial and republican, a centre of classical Chinese culture as well as home to an international expatriate group of aesthetes, Modernists and avant-gardists. While Noguchi’s time with Qi Baishi is the focus of this exhibition, the influence of Peking itself, his exposure to its intellectuals and sojourners from Europe, America and Japan was highly influential on his emergent Modernist outlook and later work.

In this presentation writer and historian Paul French (author of Midnight in Peking and The Badlands: Decadent Playground of Old Peking) seeks to explain Peking in 1930, the city itself, the people who inhabited it and their joint effect on Isamu Noguchi and his work.

Posted: October 11th, 2013 | No Comments »

I’m indebted to Anthony Clayton, one of the editors of the forthcoming collection of essays, Lord of Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer (about which more soon), for introducing me to the 1922 London stage musical Round in 50 at the recent excellent Fu Manchu in London: Limehouse, Lao She and Yellow Peril in the Heart of Empire conference at the University of Westminster. Round in 50 ran at the London Hippodrome and featured some amazing representations (fantastical of course) of China in the Jazz Age. The musical, partly written by Rohmer, was a vehicle for the music hall entertainer George Robey and is a take on Around the World in 80 Days though this time in 50 with Phil Fogg. The play featured an elaborate set for Hong Kong and a “Chinese street” where the travellers are robbed. I would direct anyone interested to this great post on the musical, featuring some pictures of the amazing Chinese set, at the blog Jazz Age Club – well worth a look if you like your stage sets a la Chinois!

I don’t have any images from the show myself but the website has plenty to keep you going – but here’s a shot of Rohmer all got up in a Chinoiserie style for you….

Posted: October 11th, 2013 | No Comments »

A quick self plug – I’ll be at Books & Co at The Greene Shopping Center in Dayton, Ohio this Friday should you happen to be in the area!

Friday Oct 11

PAUL FRENCH

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 11; 7 PM

PAUL FRENCH will discuss the paperback edition of his true-crime book, Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China. French, an historian and China expert, has opened the books on a 75-year old unsolved murder of Pamela Werner, a British schoolgirl, and offers a glimpse into the last days of Colonial Peking, delving into Peking’s seedy underworld of crime, drugs, and prostitution.

In the tradition of the true crime classics White Mischief and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, Midnight in Peking transforms a front page murder into an absorbing and emotional expose, bringing the last days of old Peking to life.