Posted: October 3rd, 2013 | No Comments »

A quick post to draw China Rhyming readers attention to this article on the most amazing map of San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1885. Click here. The map details opium houses, gambling parlours and brothels in detail and is a fascinating snapshot of the streets at that time. I know of no other map for any other Chinatown, either in America or elsewhere such as Limehouse with such detail. If you have any interest in Chinatowns then this is an absolute must see map. Indeed maps detailing ethnic populations are quite rare though I know the 1899 map of Jewish East London which is also fascinating, but no Chinese specific maps I’m afraid.

Posted: October 3rd, 2013 | No Comments »

Opening at the Ovalhouse Threatre on October 1…..

The Fu Manchu Complex

by Daniel York

Challenging the ‘Yellow Peril’ racist stereotype, five East Asian actors white up to play the traditional colonials in this hilarious murder mystery in the East End, using physical comedy and the style of the Victorian music hall in a pastiche of classic British cinema.

Who is Fu Manchu: sinister Chinaman, criminal genius, racist myth..?

Battling through clouds of opium, spiffing chaps Dr Petrie and Inspector Nayland Smith must do anything to stop the dastardly plans of evil criminal mastermind Dr Fu Manchu; but will their colonial angst allow them to do away with the villainous evil genius and save merry old England? And as their blundering leads them to ever more absurd conclusions, we ask, who is the real Fu Manchu?

2013 sees the hundredth anniversary of the publication of the first novel featuring Sax Rohmer’s lurid and fantastical racist creation, the evil Dr. Fu Manchu. A century on we re-examine the skewed perceptions that have arisen around this pervasive myth.

- 1 – 19 October, Tues-Sat 7.45pm. Previews 1 and 2 October.

Tickets

- Full: £14:00

- Under 26, Equity, BECTU: £10:00

- Concession: £8:00

- Preview: £7.00

Venue: Downstairs

Book / Box office: 020 7582 7680

Posted: October 2nd, 2013 | No Comments »

Robert Johnson’s Far China Station is an interesting addition to the naval literature on Sino-American history…

Far China Station was the first work to put nineteenth century American naval and diplomatic affairs in the Far East into clear perspective. Johnson examines the origins of the East India Squadron, defines its import role in the implementation of foreign policy and describes the dangers routinely faced by the squadron’s ships and sailors. Great and gallant ships move through the pages from the famous Olympia and the majestic Columbus to the plodding Palos. Naval heroes and the not-so-great, angry mobs, Japanese rebels, leaky boilers, imperious officials and infirm admirals are set against a background of uncertain anchorages, storms at sea, and the ravages of disease in the last years of the Old Navy.

Posted: October 1st, 2013 | No Comments »

Fantastic to see that Penguin Modern Classics (well done Penguin China!) have reissued Lao She’s great 1920s novel of London Mr Ma and Son.

Seems a good time to wander the street where Mr Ma and his son’s lodged in London after their arrival – Gordon Street, WC1 in Bloomsbury. As Lao she writes:

“Number X Gordon street was the widowed Mrs. Wedderburn’s house. It wasn’t very big, just a small three-storied building, with no more than seven or eight rooms. At the front, by the door, there was a row of green railings. The three white stone steps were scrubbed spotless, and the brass knocker on the red- painted door was polished sparkling bright. On entering the house, you came first to the drawing-room, behind which was a small dining-room. If you passed through the dining-room, took a turn, and descended some stairs, you‟d come to a further three, small rooms. Upstairs there were just another three rooms, one facing onto the street, and two at the back.”

Lao She notes – “There were quite a few Chinese living in this street.”

Sadly Gordon Street – best known for the buildings that are now part of University College London, took some direct hits from the Luftwaffe during the Blitz (actually Graham Greene was a fire watcher in the area and remembered it in his autobiography Ways of Escape, while Henry Green wrote of a firefighting crew during the Blitz working in the area in his wonderful novel Caught) so most of the houses Lao She would have known are gone now….

The UCL Union building on Gordon Street – note the old London road name signs underneath and partially obscured by the new…

Some of the larger buildings on Gordon Street….

The southern end of Gordon Street becomes Gordon Square with some remaining buildings perhaps more like Mrs Wedderburn’s

PS: don’t forget that you can still sign up (for free) to the Fu Manchu in London: Lao She, Limehouse and the Yellow Peril in the Heart of Empire conference at the University of Westminster on Friday October 4th – click here for more details.

Posted: September 30th, 2013 | No Comments »

Back in 2009 (not long after I started this blog) I posted on the rather remarkable old French Barouqe style buildings at Chaonei No. 81. This sort of building was rare enough in Peking and, of course, with all the destruction in Beijing and the removal of the old that has gone on in the last few decades it’s rather amazing they’ve survived. Anyway, after I posted Ed Lanfranco, who knows more about old Beijing than most, wrote informing me of the building’s provenance as a former American Missionary compound built around 1910 that later became the California College in China (related to the University of California). You can read Ed’s history of the buildings here.

Now, however, another twist. The New York Times’s Beijing Journal has written about the buildings which still remain empty and in some state of disrepair. Apparently they now belong to the Catholic Diocese of Beijing. Now, while the old ghost stories about the building are known – most older buildings in Beijing have such stories attached to them. This article offers a few other possible histories of the building that I’ve never heard before – that it was built by the Qing authorities for the British residents of Peking and also that it was built as a private residence for the French manager of the company that built the railway connecting Beijing to Hankou in Hubei Province.I’ve never heard either of these tales before.

What is perhaps most remarkable though is that nobody at all seems interested in restoring the building or doing anything interesting with it – even though the Diocese says that it believes it would cost only (and I say “only” in relation to the ridiculous amounts thrown at new architecture in Beijing) US$1.5mn to refurbish.

Seems the mystery continues…meanwhile the building continues to fall into an ever worsening state of disrepair.

A much better picture exists on the New York Times website

Posted: September 30th, 2013 | No Comments »

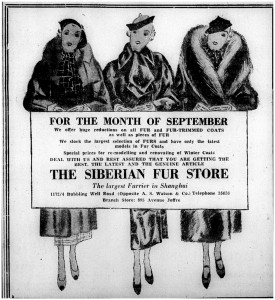

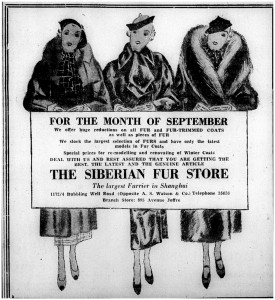

Shanghai may still be one of the best cities in the world to buy a fur and, in 1934, there was one major purveyor of furs for the discerning lady – The Siberian Fur Store on the Bubbling Well Lane (now the less charmingly named Nanjing Road West). The store was, I believe, owned and run by White Russian Jews (the Klebanoff family I think) and was a fur bank as well as fur store (so you could store you coats there in the hotter months in air conditioned vaults). It was not a store for everyone, you needed some serious gelt to make a purchase and the store was so well known and has lived in the memory of many old time Shanghainese (it made a brief appearance in Ang Lee’s Lust Caution if I remember rightly too).

Posted: September 28th, 2013 | No Comments »

As this is the centenary of the debut of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu books (The Mystery of Fu Manchu, the first book in the series, was published in 1913), and as we approach an excellent conference on Fu Manchu in London – Lao She, Limehouse and Yellow Peril in the Heart of Empire (click the link for the full programme and to RSVP) this Friday at Westminster University it seems only fitting to mark the occasion with some stills from the 1967 movie The Vengeance of Fu Manchu which included a little detour to the mean streets of Shanghai….where the actual Badlands bar of foreign wastrels in Shanghai was actually meant to be I do not know (too, too many candidates in old Shanghai) but it was filmed in County Wicklow in Ireland apparently!

Posted: September 27th, 2013 | No Comments »

You could probably find one of these still tucked away and covered in dust on the shelves of a Foreign Languages Bookstore somewhere in China if you search hard enough! This guidebook and map from 1960….incidentally showing that the old spellings were still being used at that time…..