Posted: September 11th, 2013 | No Comments »

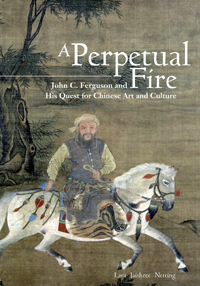

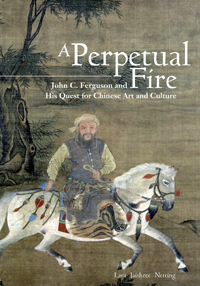

A slightly different take on Ferguson (usually most writing is about his missionary work or newspaper activities in Shanghai) from Lara Jaishree Netting…

After serving as a missionary and then foreign advisor to Qing officials from 1887 to 1911, John Ferguson became a leading dealer of Chinese art, providing the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and other museums with their inaugural collections of paintings and bronzes. In multiple publications dating to the 1920s and 1930s, Ferguson made the controversial claim that China’s autochthonous culture was the basis of Chinese art. His two Chinese language reference works, still in use today, were produced with essential help from Chinese scholars. Emulating these “men of culture†with whom he lived and worked in Peking, Ferguson gathered paintings, bronzes, rubbings, and other artifacts. In 1934, he donated this group of over one thousand objects to Nanjing University, the school he had helped to found as a young missionary.

This work offers a significant contribution to the history of Chinese art collection. John Ferguson learned from and worked with Qing dynasty collectors and scholars, and then Republican-era dealers and archeologists, while simultaneously supplying the objects he had come to know as Chinese art to American museums and individuals. He is an ideal subject to help us see the interconnections between increased Western interest in Chinese art and archeology in the modern era, and cultural change taking place in China.

Lara Netting received her PhD in East Asian Studies at Princeton University in 2009. She has held a Getty Fellowship at the Asia Society Museum and the J. Clawson Mills Fellowship at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Art collectors continuously shape and reshape our view of the artistic past, determining what later generations are able to see and how they see it. Between 1912 and 1943, the Canadian-American John C. Ferguson led a public career in Republican China that would have made a Chinese scholar proud, serving as a major government advisor and influential academician. From deep inside of the Beijing and Nanjing cultural circles, as a private collector and buyer for American museums (the Metropolitan Museum and Cleveland Museum of Art among others), he helped to dramatically redirect American interests in Chinese art from the taste of Japanese aficionados to that of the Chinese literati. Lara Netting’s thorough study brings the remarkable and complex John Ferguson back to life. She restores to him the credit he has long deserved, while at the same time using his example to demonstrate how our definition of ‘art’ is an ever-changing construct.â€

—Jerome Silbergeld, Princeton University

“Missionary, dealer, collector, and scholar, John Ferguson aspired to the lifestyle and status of a Chinese literatus and was the first Westerner to seriously collect calligraphy as well as Ming and Qing painting. Lara Netting’s meticulously researched study offers a long overdue assessment of Ferguson’s life and legacy—both in China and the West.â€

—Maxwell K. Hearn, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Posted: September 10th, 2013 | No Comments »

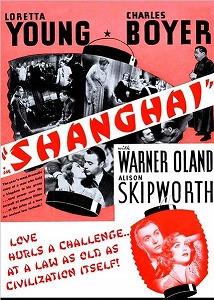

Well apparently, according to Ben Urwand’s fascinating new book The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler, it was the 1935 Charles Boyer/Loretta Young movie Shanghai. It seems Hitler demanded the projector be switched of half way through.

Why this dislike of an otherwise rather unexceptional film about Shanghai? In the movie Loretta Young and Boyer fall in love – Boyer (Dmitri Koslov, a half-Russian/half-Chinese millionaire industrialist in the film) is actually Eurasian, though denying his mixed heritage. Loretta Young is an all-American gal and, as the film’s slogan exclaimed, “Love hurls a challenge at a law as old as civilisation itself.” Hitler though wasn’t much of a fan of mixed heritage or mixed relationships and couldn’t stand the film. As a footnote Warner Oland (of Shanghai Express and numerous Charlie Chan flicks) appears in yellowface, as he so often did. Adolf should have stayed to the end – it all ends badly for the leads (or well, if you’re Hitler I suppose) and true love doesn’t win out.

the original, and rather mixed, 1935 New York Times review is here by the way

And here is a review of Urwand’s book, from which I culled this interesting fact about Shanghai

Doomed mixed race love – hated by Adolf!

Posted: September 9th, 2013 | No Comments »

A quick diversion from the China history stuff to note the publication of the latest book in my series for Zed Books called Asian Arguments (see all the previous titles here). Gabriel Lafitte’s Spoiling Tibet (in paperback and as an e-book) is, I think, an incredibly important piece of research about both the despoilation of Tibet, the continuing destruction of traditional ways of life, rampant piratical capitalism by Chinese interests across the plateau and just how Beijing’s actions in digging up Tibet affect you and what you buy wherever you are….I don’t expect this book will be much liked by Beijing or the Han nationalism crowd but hopefully it will add another layer to the debate around Tibet’s current crisis and future.

Spoiling Tibet

China and Resource Nationalism on the Roof of the World

Gabriel Lafitte

The mineral-rich mountains of Tibet have been landscapes of solitude, where the greatest yogis withdrew from society to deeply realize the nature of the human mind. Those sacred landscapes and pilgrimage routes, hitherto largely untouched by China’s growing economy, are now officially designated as mineral extraction enclaves. China’s 12th Five-Year Plan, from 2011 to 2015, calls for massive investment in copper, gold, silver, chromium and lithium mining, with devastating environmental and social outcomes.

Despite great interest in Tibet worldwide, Spoiling Tibet – the first book that investigates mining at the roof of the world – is an entirely unique authoritative guide through the torrent of online posts, official propaganda and exile speculation.

Reviews

‘This is not just a simple book on minerals and mines in Tibet. It is the first serious study of the subject. It is also a book that tackles the issue of Tibet’s sacred mountains, which are at present being badly damaged by the development of mines. At a time when Tibetans are fighting to save their physical environment as well as their religious landscape from destruction, an informative book such as this is most welcome. Written in a comprehensive and lively style, it sheds light on Chinese policies regarding Tibet’s minerals resources. It is a must read for anyone interested in Tibet and in the fragility of the environment.’ – Katia Buffetrille, École Pratique des Hautes Études, co-editor of Authenticating Tibet: Answers to 100 China Questions and editor of Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World

‘Spoiling Tibet contains a fascinating wealth of information about mining in contemporary Tibet. Bringing reflections on the relationship between landscape and enlightenment together with analyses of capital flight, primitive accumulation, and the dynamics of Chinese state capitalism in an era of globalization, the book is packed full of often counter-intuitive insights. Lafitte highlights the voices of Tibetans who are excluded from decision-making and object to environmentally destructive mining, while also arguing that to date, China has not exploited Tibetan minerals as much as commonly presumed.’ – Emily T. Yeh, assistant professor, University of Colorado at Boulder

‘Gabriel Lafitte is one of the few analysts wtih a profound knowledge of the extent and impacts of mineral exploitaiton in Tibet. This book is a vital reference point for anyone inerested in the future of Tibet.’ – Isabel Hilton, editor of chinadialogue.net

Table of Contents

A note on the geography of Tibet

Maps of Tibet and China

Introduction

1 Tibet in its own right

2 Gold rush in Tibet

3 Reach of the revolutionary state

4 Chromite globalization

5 Capitalizing on Tibet: privatizing the treasure house

6 Intensive exploitation

Conclusion

Notes

Further reading on Tibet

Index

About the Author:

Gabriel Lafitte has spent years living with Tibetans, in exile and in Tibet. Based in Australia, he researches the impacts of Chinese policies on the Tibetan Plateau, and regularly trains young Tibetan professional environmentalists and advocates. Decades of immersion in Tibetan culture, and a dozen journeys around China, have given him an insider/outsider perspective on two great civilizations in conflict. He is an experienced public policy adviser with expertise in development, biodiversity and resource management policy. He has authored numerous reports, submissions and a 2006 book on the Dalai Lama’s teachings Happiness in a Material World.

Posted: September 8th, 2013 | No Comments »

Fu Manchu in London: Lao She, Limehouse and Yellow Peril in the Heart of Empire

Â

Conference Overview

Â

The Department of English, Linguistics and Cultural Studies is pleased to be hosting a one-day conference on the occasion of three auspiciously inter-related events this autumn: the publication by Penguin Modern Classics of Lao She’s forgotten masterpiece of 1920s Chinese London, Mr Ma and Son, the launch at the Ovalhouse Theatre of Daniel York’s satiric play, The Fu Manchu Complex (dir. Justin Audibert), and to mark the centenary of the evil genius – a collection of essays edited by Phil Baker and Antony Clayton, Lord of Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer (Strange Attractor Press, 2013). One hundred years later we re-examine the skewed perceptions that have arisen around his pervasive influence.Â

Conference Speakers – in order of appearance

Phil Baker

Ross Forman

Robert Irwin

Antony Clayton

Julia Lovell and Paul French

Daniel York and Justin Audibert

The conference will be held at the University of Westminster, New Cavendish Street (room t.b.a) on Friday, October 4th, 9.30-4.00. Admission is free. Please register your place by emailing Dr Anne Witchard here:

anne@translatingchina.info

Posted: September 7th, 2013 | No Comments »

Personally, I could not be more thrilled that William Dolby’s translation of Mr Ma and Son is finally out and available (with an intro by Julia Lovell and a fantastic Limehouse Chinatown cover!) – a great Lao She novel and a great novel of 1920s London (and for those who like it, Lao She and London then a perfect companion read is Anne Witchard’s Lao She in London (Royal Asiatic Society-Hong Kong University Press, 2012), which sets the scene and describes the milieu perfectly.

‘Lao She’s bittersweet tale of a clash of cultures, generations and politics in twenties London has never been better brought to life than in Dolby’s marvelously fluent translation. This is the city as you have never seen it before, caught through Asian eyes, and by one of China’s finest modern novelists.’

– Robert Bickers, author of Empire Made Me and The Scramble for China

‘At last a translation of Lao She’s neglected masterpiece that does justice to his comic genius.’

– Anne Witchard, author of Lao She in London

‘This is an acute observation of London through the eyes of China’s supreme social observer of the twentieth century.’

– Paul French, author of Midnight in Peking and The Badlands: Decadent Playground of Old Peking

Mr Ma and his son Ma Wei move to London from China to run an antiques shop and find that their presence brings with it mixed feelings and deeply rooted cultural misconceptions. As they try to navigate the streets of London and the social conventions thrown at them by 1920s English society, the Mas encounter all sorts from their well-meaning landlady and her carefree daughter, to old China hands the Reverend Ely and his formidable wife. And, as the Mas go about building their new lives in London, finding love in unexpected places, and striving to maintain a sense of cultural self, their own relationship finds itself tested.

Â

Based on his own experiences in London, Lao She’s Mr Ma and Son is a compelling account of an often overlooked slice of London history. A witty story of cultural give-and-take written by one of China’s best-loved writers, Mr Ma and Son was a significant contributor to the early twentieth-century conversation on Sino-British relations and it is a masterpiece of the modern classical cannon.

Â

Lao She was born in Peking in 1899 to a poor Manchu family. In his mid-twenties, Lao She left China to teach Chinese at the University of London. In London he developed an appetite for English literature. By the time he returned to China, he was an established author, known for his humourist style, and he continued to write novels, non-fiction works, and plays. In the sixties, Lao She was labelled an anti-Maoist and a counter-revolutionary by the Red Guards. In August 1966 he committed suicide in Peking. In 1979 Lao She was posthumously rehabilitated by the Communist Party.

Posted: September 6th, 2013 | No Comments »

A Cushy Berth – Ralph Shaw – 1937

Englishman Ralph Shaw had trained as a cub reporter in his native Derby before joining the army and shipping out to Shanghai. He managed to get out of the military, which didn’t suit him much due to the low pay and early nights, and land a job with the North-China. If we know anything about just how much sex was available and enjoyed in the International Settlement in its final days before the Japanese takeover then it is largely thanks to Shaw’s remarkably frank and graphic memoir Sin City which combines political analysis and newsroom memories with a long list of sexual escapades and encounters. Shaw chronicled long nights in the notorious Blood Alley bar street, knee tremblers in the cinema and his patronage of gangster Big Eared Du’s Silver Taxi Company, which basically provided fellatio on four wheels.

Garrison Man

Shanghai was a cushy berth – dead easy compared with Aldershot and Bulford. For the first time in my life I had a manservant or, rather, I shared his services with others who lived with me in a barrack room at the British Hospital in downtown Shanghai, only a few hundred yards from the Bund waterfront.

The ‘room boy’ took over the chores that we did ourselves back in Blighty – making the beds, ‘bumping’ the floor, polishing our buttons, cap badges, blancoing our belts, cleaning our boots and so on.

So we lived like little tin gods, mostly prostrate on our beds reading such pirated literature as ‘My Life and Lovers’ by Frank Harris while our man – an ever smiling Chinese gentleman – bustled about the room and generally helped us to stave off exhaustion.

After leaving the Dilwara (1) I had been assigned to the General Staff (i) office in the headquarters of the Shanghai Municipal Council on Kiangse Road, just beyond the Anglican Holy Trinity Cathedral. The ‘i’ denoted that we were an intelligence bureau and it was my job, as clerk, to type out on stencils a regular series of confidential reports which were sent to London, Hong Kong and other military nerve centers.

…………………………………………………………………..

Not a hundred yards away from us in Central Road was the Handy Bar run by an American, Jimmy James, late of the US 15th Infantry, who had stayed on in China after discharge and had opened two restaurants both of which flourished under the title, Jimmy’s Kitchen.

The Handy Bar – Hyson called it the ‘Randy Bar’ – owed its popularity among hospital personnel to the fact that Jimmy had staffed it with a chorus line of Russian beauties, bar girls whose job was to entice solid cash from lecherous soldiers out on the spree.

Unlike British barmaids, the girls pulled no beer pump handles. In fact there was no draught beer available. Drinks came in bottles and were served by Chinese ‘boys’ who could be any age from 20 to 70 or thereabouts. The girls decorated the joint, sat with the lads and coaxed by various means ‘drinks’ – usually coloured water or tea – out of them.

Sapper Mann took me along to the Handy Bar where the long-legged, busty beauty of one girl, Nadya, had John Thomas up in appreciation long before she joined us at the Sapper’s invitation. He had the cash. I didn’t. He felt generous – willing and ready to play the host for newcomer.

Leg! I loved ‘em. Nadya had a pair that dazzled the eyes – long, shapely, stocking-clad, supported by high-heeled, shiny shoes. And her neckline was low enough to suggest that a couple of size 38s might break loose if she bent any lower over the table. I, for one, was ready to catch them!

Dark-haired, brown-eyed, she resembled Dorothy Lamour though it would have been a pity to cover up those legs with a sarong.

She noticed that my eyes were bulging and immediately found that there was something wrong with one of her shoes. She stood up, placed one foot on the chair so that I got almost a worm’s-eye view up to suspender-belt height, bent forward, which temporarily had my eyes going up and down like a yo-yo, and began to fiddle about with the ‘offending’ footwear.

Like Olga Polovski, the Russian spy, she was in imminent danger. Poor old Olga, so the story had it, was going to be executed by a firing squad for conning Allied secrets in World War One. She appeared before the squad in a fur coat and, as the men in front of her took aim with their rifles, discarded the garment to stand completely and beautifully naked. She fell dead – riddled with fly buttons.

Certainly the strain on my flies was intense, a point which Nadya had duly noted. Tumescence had to be maintained – it meant generosity, drinks. The leg show continued. She had considered the lure of bosom and, after weighing up my reaction carefully, had come to the conclusion that while I might be a tit man it was for certain that legs would arouse benevolence as far as I was concerned. She was right.

Unfortunately, my financial embarrassment stopped me ordering another round and Sapper was obviously reaching zero mark. He suggested we should leave.

Ralph Shaw, Sin City, (Everest Books, 1973, London)

Â

Â

(1) The troopship SS Dilwara built by the British India Line in 1936 and operating under charter to the British government. The Dilwara could carry 1,150 troops a voyage.

Â

Posted: September 5th, 2013 | No Comments »

New Life – Edna Lee Booker – 1937

In 1937 Edna Lee Booker arrived back in Shanghai with her young daughter Patty and her son John Jr. after a break and found a very different city.

Read Edna’s first arrival in 1922 here

Desolation

Rain swirled about our liner as it made its slow way up the Whangpoo toward Shanghai. We were on deck, eager for our first glimpse of Shanghai’s sky line; but, long before we saw the tower of the Cathay (1) looking against a leaden sky, the knowledge that we were returning to a Shanghai very different from the gay, prosperous city we had left many months previously was brought sharply home.

On either side of the river was desolation: aftermath of war. A large portion of Shanghai’s great industrial districts lay in ugly ruins. Gutted roofs, jagged walls loomed through the rain, mute evidence of the terror which had so recently broken over the city. There was no life about these ruins. It was as if time stood still there.

Patty began to cry.

One afternoon shortly before we sailed for China, we had gone to a children’s cinema matinee. The newsreel had shown the bombing of Shanghai. In horror I watched great black clouds of smoke, shot with flame, engulf buildings crashing with the explosion of bombs. Patty became hysterical; John Jr., joined in the hisses which filled the house. We left at once.

And now on the boat – face to face with the reality of it all – Patty had again broken into sobs. The sight of those crooked walls from which empty windows stared like crazed eyes was too much for her. Only the sight of her dad on the landing wharf, waving to us through the rain, finally quieted her.

When we landed, Patty clung to her father as if she would never let him go. It was only then I realized that she had been fearful for her dad during those weeks in California, where radio commentators and newspaper headlines had recounted frightful event in the Sino-Japanese war over Shanghai.

Rain, which fell from low-hanging, gloomy skies for days after our return, intensified the misery met on every hand in the settlements, and outside the foreign protected areas where all was chaos.

Great Shanghai was a mass of ruins.

Practically all that was left standing of the teeming port city was the comparatively small foreign protected areas of the International Settlement and the French Concession, with certain outside roads, and a few blocks of the Chinese city bordering the French Concession which had come to be known as the Nantao Refugee Zone (2).

Later my husband drove me through the war areas of Chapei and the northern and eastern districts.

The sight of endless blocks of sprawling ruins was shattering. Previously two million hard-working Chinese had lived there. Now not a soul was to be seen: not a child or even a wonk dog. Those sodden piles of ruins which stretched so grotesquely in every direction had been mills, filatures, factories, tenements, schools, shops, temples, homes. There was an eerie silence over all.

A Chinese with us explained that the ghosts of all those thousands who had been killed round about hovered there.

He pointed out a partially wrecked terrace from which strange noises, like the clanging of gongs, were heard at night. Innumerable “devils†gathered at the ruins of the North Station after ten o’clock, he said: and Japanese sentries seldom ventured abroad after sundown in those stretches of waste. On certain nights, when the moon was bright, kuei huo (devils’ fire balls, ignes fatui (3)) could be seen bounding down the broken streets and passageways. Japanese guards that followed those will-o’-the-wisp lights were found dead in the morning.

The gutted walls of the open-ended Civic Center buildings seemed mockeries of lofty aspirations to me. In their architectural beauty they had pictured the ancient glories of the emperors, but the dreams and hopes of a progressive New China were implanted in their foundations. Less than a month before the outbreak of hostilities, the Greater Shanghai City Government had celebrated its tenth anniversary with a gala twelve-day festival in the Civic Center, and the foreigners as well as the Chinese had shown pride in this splendid achievement of the Kuomintang. Rain swirled in devilish glee through the wrecked wing of the Museum building, which had – oh, so recently! – housed art objects, valuable scrolls and rare volumes of ancient Chinese literature. A sagging telephone wire whined crazily in the wind.

It was too depressing to look further. I wanted to get away from that maze of destruction, back to the comparative normality of the International Settlement.

Edna Lee Booker, News Is My Job: A Correspondent in War-Torn China, (Macmillan, 1940, New York)

1) The Cathay Hotel on the BundÂ

2) The Nantao Refugee Zone was a safe zone for Chinese refugees in Shanghai during the months after the Japanese attack on the city on August 1937. It was organized by a French Jesuit priest Father Jacquinot and so became known as the “Jacquinot Zoneâ€.

3) A phosphorescent light that hovers or flits over swampy ground at night, which in myths misleads or deludes travelers.

Â

Posted: September 3rd, 2013 | No Comments »

Utterly Different From That Already Familiar – George N Kates – 1933

George Norbert Kates was an art historian, curator of oriental art and author of several books including Chinese Household Furniture (1947) and The Art Of Being Old (1956) as well as The Years That Were Fat (1952), a memoir of old Peking, from which the excerpt below is taken. Kates lived in China between 1933 and 1940, and then again briefly between 1943-1945.

Sheer Folly

Early in the following year, now well launched upon a course that might seem to other, I knew, sheer folly, I decided to take passage in a ship, and go to China itself. The reader should know at this point that I had very little money with which to do this. A margin account with a large brokerage firm that had gone into bankruptcy had transformed nearly all my Hollywood earnings into pure fool’s gold. In time, I came to see that this final transmutation, this reversion of the intrinsically base and unstable back to itself once more, did fittingly end my California adventure.

So I went to the Boston Common, one tender spring afternoon, when thoughts floated naturally away towards other horizons, to do business at Cook’s. With a ticket in my pocket for a berth n a ship going trough the Panama Canal, and thence to Victoria, in British Columbia (where I was to transfer to the Canadian Pacific’s white Empress of Asia), I felt confident that I had veered not away from, but comfortingly nearer to my true, if still little revealed course.

There came a morning, after several weeks of travel, when looking through the ring of my brass porthole, low in the ship, I gazed for the first time down upon muddy and swirling, yellow-brown and summer-warm waters, the estuary of the Yangtze. Later, after a long day, Shanghai finally loomed ahead, the smoke-filled air of its curving Bund reminiscent of mighty London. Here, halfway across the world, I had reached a metropolis again – yet one with components utterly different from those already familiar.

Here I disembarked, each minutes filled with new sensation. Half-stripped coolies in multitudes, turbaned Sikhs, White Russian water police; occasional curving Chinese roofs between newer buildings, rickshas, giant advertisements in characters: actors and scenery, all were different. Passing through customs I made my way without haste, through dead urban air, to an international hotel. I well knew that this was not China, although there were native elements in the amalgam.

In Shanghai, therefore, I remained for but one night, dining amid the babble of the hotel restaurant; and departing on that following for Nanking. I wished to be on my way. Nanking, then the capital, became another torrid day, spent largely from breakfast onward in the darkened and shady house of our Consul General. That evening at Pukow, the broad Yangtze crossed by ferry in late rosy light, voluble Chinese in fluttering silk gowns fanning themselves beside me, I entered the Shanghai Express, that very slow train, which crawled haltingly towards the tawny northern plains, to my destination from the beginning, Peking.

Somewhere on the journey, as the wind blew the golden dust of North China over the earth’s gentle slopes, amid low mud-walled farmhouses and everywhere grave mounds made of the soil itself, I arrived in the country that for the next seven years of abundance was to become intimately my own.

Â

George N Kates, The Years That Were Fat: Peking, 1933-1940,

Â