Posted: June 25th, 2013 | No Comments »

My thanks to Bill Lascher, who is currently researching a new biography of the great American China correspondent Melville Jacoby, sadly killed in a plane crash during World War Two. Bill has already published a short piece of Jacoby’s writing from Chungking during the war as an e-book Monsieur Big Hat.

As his research progresses he is turning up lots of fascinating details about Jacoby’s time in China – this from a letter Melville wrote in July 1937 from Peking to his parents which will interest anyone who’s read Midnight in Peking and is familiar with the murder of Pamela Werner…

“Then there was a brutal killing of an English girl a few months back just after an argument. Lots of undercover work up here that doesn’t receive publicity but comes to light now. Some naturally is untrue.”

Posted: June 24th, 2013 | No Comments »

Gao Yunxiang’s Sporting Gender looks extremely interesting….

When China hosted the 2008 Summer Olympics — and amazed international observers with both its pageantry and gold-medal count — it made a very public statement about the country’s surge to global power. Yet, China has a much longer history of using sport to communicate a political message.

Sporting Gender is the first book to explore the rise to fame of female athletes in China during its national crisis of 1931-45 brought on by the Japanese invasion. By re-mapping lives and careers of individual female athletes, administrators, and film actors within a wartime context, Gao shows how these women coped with the conflicting demands of nationalist causes, unwanted male attention, and modern fame. While addressing the themes of state control, media influence, fashion, and changes in gender roles, she argues that the athletic female form helped to create a new ideal of modern womanhood in China at time when women’s emancipation and national needs went hand in hand. This book brings vividly to life the histories of these athletes and demonstrates how intertwined they were with the aims of the state and the needs of society.

Yunxiang Gao is an associate professor of East Asian history at Ryerson University.

Posted: June 23rd, 2013 | 1 Comment »

I spent a couple of days in Yichang this week and thought I’d dig out a few reminiscences about the place from the great master Old China Hand, Carl Crow. Crow journeyed up the Yangtze to Sichuan in 1935 partly for a spot of tourism and to see the Three Gorges and partly to see some advertising clients of his up in Sichuan. He decided (though a new aeroplane service was available) to make the voyage by boat….

The Yangtse at Yichang this week…

“As usual with Carl what should have been a routine journey to Sichuan turned into a more informative trip than he could have hoped for. In the mid-1930s Sichuan was still considered hopelessly remote. The inland treaty port of Yichang in Hubei, the ‘Gateway of the Gorges’, was a thousand miles from Shanghai while steam navigation went only as far as Chongqing, a further 410 miles upriver from the rapids at Yichang through the famous Three Gorges. Crow travelled by Yangtze River Steamer from Shanghai with Yangtze White Dolphins dipping and diving in the boats wake. The steamer departed in the late afternoon, passing Zhenjiang), a city noted for the quality and the all-pervasive smell of its locally produced vinegar, in Jiangsu, at the junction of the Grand Canal with the Chang River and arrived in Nanjing a day later. Though the new rail service was only an overnight journey Crow considered the standard of hotels in Nanjing so poor he preferred to stay on the steamer. From Nanjing it was a further journey upriver through the commercial centre of Wuhu, the tea-producing town of Kiukiang and Anking with its famous Wind Moving Pagoda for four days before arriving at Hankow and the junction of the Yellow and the Yangtze Rivers. Along with the famous White Dolphins Crow also glimpsed the miniature Yangtze alligators as well as experiencing the famously volatile currents, known as chow chow waters by the ship’s captains, north of Anqing.

Between Shanghai and Hankow the Yangtze was broad and deep and in the summer season when the river was bulging with melting snow waters from Tibet navigable by ocean going vessels. However, above Hankow the Yangtze changed its nature considerably. The so-called middle Yangtze, between Hankow and Yichang, became narrow, crooked, sallow and far harder to navigate meaning that passengers had to transfer to smaller passenger boats for the remainder of the journey which could only be undertaken during daylight hours as by night the river was simply too treacherous.

Hankow to Yichang was a voyage of 400 miles and took longer than the 600 miles from Shanghai to Hankow. At Yichang the middle Yangtze became the upper Yangtze and a further transfer to an even smaller passenger boat was required to proceed and complete the 410 miles to Chongqing. The small vessels that traversed the Yangtze between Yichang and Chongqing were highly powered in proportion to their size to deal with the swift churning currents and rapids. It was still often the case that no amount of engine power was of use and the boat had to be steered through the Gorges, and ominously named spots like the Little Orphan Channel, using towlines pulled by several hundred Sichuan peasants, or Trackers, dragging the boat by walking along narrow paths cut into the cliff face on either side of the torrent below. The upper Yangtze was at that time known as a “graveyard for ships†and, according to Crow, carried the highest maritime insurance rate in the world. As Crow’s ship inched up through the Gorges he could see the funnels of sunken ships dotting the water to remind passengers of just how unforgiving the Yangtze could be.”

From my biography of Crow – A Tough Old China Hand

Posted: June 20th, 2013 | No Comments »

This year’s London Antiquarian Book Fair at Olympia was the usual host of things that are lovely but you can’t afford (or maybe you can…but I can’t!). One particularly lovely China-related item attracted a lot of attention – a programme for the second day of a horse (Mongolian ponies really) racing event at Foochow (Fuzhou) in 1885 courtesy of the dealers Voyager Press Rare Books of Canada (who have lots of lovely Chin and Asia stuff on their website). The event was on Tuesday, December 15th 1885 and you can expect all that all of treaty port society was there – tea traders massing in the stands! Races that day included the “Tea Merchants Cup” and the “Min” Stakes named for the local Chinese dialect of the region and the “Chaasze Cup” named for a famed British tea merchant. To top it all the programme was printed on silk! The sellers were asking GBP650 – not sure if anyone was lucky enough to have 650 quid to part with to let them own this beautiful object of old treaty port China?

You can see the programme here

Foochow around that time

Posted: June 19th, 2013 | No Comments »

Even I am amazed at Dikotter’s rate of output!! This of course looks excellent and would appear to chime with the general ChinaRhyming view of modern Chinese history – The Tragedy of Liberation….

In 1949 Mao Zedong hoisted the red flag over Beijing’s Forbidden City. Instead of liberating the country, the communists destroyed the old order and replaced it with a repressive system that would dominate every aspect of Chinese life. In an epic of revolution and violence which draws on newly opened party archives, interviews and memoirs, Frank Dikötter interweaves the stories of millions of ordinary people with the brutal politics of Mao’s court. A gripping account of how people from all walks of life were caught up in a tragedy that sent at least five million civilians to their deaths.

Posted: June 18th, 2013 | No Comments »

Friday 21st June 2013

7 pm for 7.30pm start

RAS Library at the Sino-British College

1195 Fuxing Zhong Lu

PROFESSOR BENJAMIN A ELMAN on

19th Century Science in Shanghai

After the Taipings were defeated, the weakened Qing dynasty and its literati-officials faced up to the new technological requirements to survive in a world filled with menacing, quickly industrializing nations. Literati, especially those in the treaty port of Shanghai who had worked with the Protestant missions in the 1850s, began in the 1860s to move from their London Missionary Society positions to teaching and translating the natural sciences for the government’s new westernizing institutions such as the Jiangnan Arsenal in Shanghai. They built bridges between post-industrial revolution science and traditional Chinese natural studies.

In the 1850s, new Protestant journals such as the Shanghae Serial (Liuhe congtan) introduced new fields in the Western sciences in Chinese, rigorously categorizing them under the general rubric of “learning based on the investigation of things and the extension of knowledge” (gezhi xue). The traditional literati notion of investigating things (gewu)moved from representing a methodological universal for classical learning, encompassing natural studies, to designating a specific domain of knowledge within the natural sciences.

Through the translation work of Alexander Wylie, Li Shanlan, and others involved in the Shanghae Serial, the investigation of things demarcated the new Western natural sciences. A scientist was now called “someone who investigates things and extends knowledge” (gezhi shi or gewu jia). The British Royal Society was translated in the Shanghae Serial as the “Public Association for Investigating Things and Extending Knowledge” (Gezhi gonghui), while the French Academy of Science was called the “French State School for Investigating Things and Extending Knowledge” (Falangxi gezhi taixue) in Chinese.

Â

After the Shanghae Serial stopped publication in 1858, the first issue of the Shanghai-based Scientific and Industrial Magazine appeared in February 1876. There were three breaks between the three series of publications before it finally ceased in 1892. Volumes 1-2 appeared in 1876-77, volumes 3-4 in 1880-81, both as monthlies, and volumes 5-7 in 1890-92 (published as a quarterly).

Benjamin Elman is Gordon Wu ’58 Professor of Chinese Studies, professor of East Asian Studies and History, and chair of the Department of East Asian Studies at Princeton University. He works at the intersection of several fields including history, philosophy, literature, religion, economics, politics, and science. His ongoing interest is in rethinking how the history of East Asia has been told in the West as well as in China, Japan, and Korea.

Professor Elman is currently studying cultural interactions in East Asia during the 18th century, in particular the impact of Chinese classical learning, medicine, and natural studies on Tokugawa, Japan, and Choson, Korea. The editor, author, or coauthor of numerous publications, Elman’s recent books include Classicism, Examinations, and Cultural History (2010); A Cultural History of Modern Science in China (2009); and a textbook for world history, Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: A History of the World from the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present (2008). Elman has also been effective in building relationships between Princeton University and institutions in East Asia, and has taught extensively at Fudan University in Shanghai and the University of Tokyo.

RSVP: to RAS Bookings at: bookings@royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

Â

ENTRANCE: 30 rmb (RAS members) and 80 rmb (guests). Includes a glass of wine or soft drink. Priority for RAS members. Those unable to make the donation but wishing to attend may contact us for exemption.

Â

MEMBERSHIP applications and membership renewals will be available at this event.

Â

RAS MONOGRAPHS – Series 1 & 2 will be available for sale at this event. 100 rmb each (cash sale only)

Â

WEBSITE: www.royalasiaticsociety.org.cn

Posted: June 17th, 2013 | No Comments »

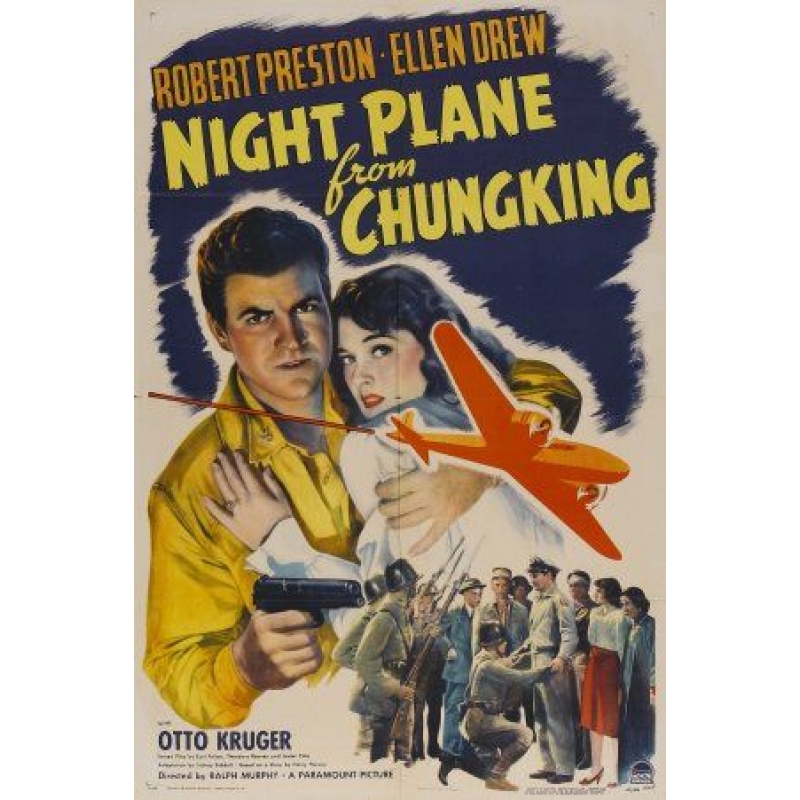

Talking of Rana Mitter’s new book on China during the war yesterday I thought I’d mention the almost forgotten 1943 wartime propaganda movie Night Plane From Chungking. A quite interesting B-movie that was essentially a remake of Josef von Strernberg’s much better Shanghai Express (1932 – with Dietrich, Anna May Wong etc etc). Night Plane has no great stars or particular talent attached to it though there are plenty of dodgy White Russians, duplicitous characters etc. A bit more on it here.

Posted: June 16th, 2013 | No Comments »

Rana Mitter’s long awaited history of the Sino-Japanese War and Chungking….and an interview in the China Daily on the book…

Different countries give different opening dates for the period of the Second World War, but perhaps the most compelling is 1937, when the ‘Marco Polo Bridge Incident’ plunged China and Japan into a conflict of extraordinary duration and ferocity – a war which would result in many millions of deaths and completely reshape East Asia in ways which we continue to confront today.

With great vividness and narrative drive Rana Mitter’s new book draws on a huge range of new sources to recreate this terrible conflict. He writes both about the major leaders (Chiang Kaishek, Mao Zedong and Wang Jingwei) and about the ordinary people swept up by terrible times. Mitter puts at the heart of our understanding of the Second World War that it was Japan’s failure to defeat China which was the key dynamic for what happened in Asia.