Posted: August 10th, 2013 | No Comments »

An interesting review in the July edition of the Literary Review by Timothy Brook (of the excellent reads The Troubled Empire and Vermeer’s Hat etc) of Geoffrey Parker’s Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century that may not have immediately come to the attention of China Watchers and China Rhymers. Interesting in that the book discusses the global notion of the terrible seventeenth century rather than the Euro-centric approach to its awfulness (30 Years War, etc) that many of us got at school. It might also be interesting to those looking to China’s past as a possible guide to its future and indications of just how fast things can fall apart….

Basically – China at the start of the century was in passably good shape, reasonably well governed and with a strong economy. However, within 30 years it had descended into fratricidal civil war, the fall of Peking to the mob, suicide of the last Ming emperor in 1644 and then the fall of the Ming to the Manchus from outside China’s borders and the shift in dynasties. That ended China’s growth and saw a retreat into isolation till nearly the end of the century and arguably beyond.

Parker’s book looks beyond the immediacy of war, bad governance and rotten emperors to the environment – global cooling, reaching its peak in the seventeenth century and destroying harvests leading to famine with little in the way of a government response, emptied treasuries and reserves, epidemics and sickness the healthcare system couldn’t deal with and, to use today’s terminology, a breakdown in “social harmony”. Throw in natural disasters like earthquakes and a rash of dragon sightings (these days it’s usually UFOs) and it all got too much for the Ming.

So, a useful guide to China’s role in the global economy and its perilous position in the 1600s – as to parallels to today’s natural disasters, healthcare and environmental degradation and any possible dragon sightings, I’ll leave you all to draw your own conclusions on where that leaves “social harmony” and the prospects of regime survival in the twenty first century.

Revolutions, droughts, famines, invasions, wars, regicides, government collapses—the calamities of the mid-seventeenth century were unprecedented in both frequency and extent. The effects of what historians call the “General Crisis” extended from England to Japan, from the Russian Empire to sub-Saharan Africa. The Americas, too, did not escape the turbulence of the time.

In this meticulously researched volume, master historian Geoffrey Parker presents the firsthand testimony of men and women who saw and suffered from the sequence of political, economic, and social crises between 1618 to the late 1680s. Parker also deploys the scientific evidence of climate change during this period. His discoveries revise entirely our understanding of the General Crisis: changes in prevailing weather patterns, especially longer winters and cooler and wetter summers, disrupted growing seasons and destroyed harvests. This in turn brought hunger, malnutrition, and disease; and as material conditions worsened, wars, rebellions, and revolutions rocked the world.

Parker’s demonstration of the link between climate change, war, and catastrophe 350 years ago stands as an extraordinary historical achievement. And the implications of his study are equally important: are we adequately prepared—or even preparing—for the catastrophes that climate change brings?

Geoffrey Parker is Andreas Dorpalen Professor of History at The Ohio State University, and winner of the 2012 Heineken History Prize. Among his many books is The Grand Strategy of Philip II, published by Yale.

Posted: August 9th, 2013 | No Comments »

A nice new book of images from the collections of the British Museum from Mary Ginsberg – The Art of Influence….

In revolutionary and wartime societies, propaganda is considered a vital part of education and political participation. Propaganda encourages or condemns; reinforces existing attitudes and behaviour; promotes social membership within nation, class or work unit. Where political transformation (communist revolution, end of colonial rule) has occurred before widespread modernization, with the majority population illiterate, art was the most effective way to communicate the message. Drawing on the British Museums wide-ranging collections, this intriguing and thought-provoking catalogue provides a fascinating contextual survey of political art across Asia, covering the period from approximately 1900 to 1976 (the end of the Cultural Revolution and Maos death; the end of the Vietnam War).

Posted: August 8th, 2013 | No Comments »

I thought it might interest China Rhyming readers to see the new collection from Olivia von Halle “inspired” (as designers say) by 1920s Shanghai…some pics below and more here.Â

As they say – “Our long-awaited Autumn/Winter 2013 collection launches online today, inspired by the opulent jewel tones and Art Deco prints of Shanghai in the 1920s. The classic Lila and Alba styles return re-imagined in sumptuous new prints and Coco also returns in bold new colours. We are excited to introduce two new kimono-style robes to the collection; the ‘Mimi’ short robe and ‘Queenie’, a full-length robe created from an incredible 10 metres of silk.”

Posted: August 7th, 2013 | No Comments »

Following on from a previous post about China-related covers from Penguin…here’s a few more…randomly….

Posted: August 6th, 2013 | No Comments »

I’ve posted before on Frenchtown’s leading French vintner (and Free French hero in World War Two at a time when most Shanghai French lined up with Vichy pretty quickly) Roderick Egal (here, here and here) but he wasn’t alone in selling French booze. L. Rondon, based on the Avenue Edward VII (the French side of old Yanan Road), also dealt in fine wines and spirits from the old country in the 1930s.

Posted: August 5th, 2013 | No Comments »

An interesting looking new book on Shanghai’s tabloid press prior to the founding of the Republic – Merry Laughter and Angry Curses by Juan Wang….

The end of the Qing dynasty in China saw an unprecedented explosion of print journalism. Chinese-owned newspapers, first encouraged by Emperor Guangxu to inform and educate an increasingly literate public, had by the turn of the century become more powerful than the state had ever anticipated or desired. Yet it was not the dabao, or “important” papers, that proved most influential. Rather it was the xiaobao, the “little” or “minor” papers — with their reputation for frivolity — that captivated and empowered the public.

Merry Laughter and Angry Curses reveals how the late-Qing-era tabloid press became the voice of the people. As periodical publishing reached a fever pitch, tabloids had free rein to criticize officials, mock the elite, and scandalize readers, giving the public knowledge about previously unspeakable and unprintable ideas. In the name of the people, tabloid writers produced a massive amount of anti-establishment literature, whose distinctive humour and satirical style were both potent and popular. This book shows the tabloid community to be both a producer of meanings and a participant in the social and cultural dialogue that would shake the foundations of imperial China and lead to the 1911 Republican Revolution.

Posted: August 4th, 2013 | No Comments »

Apparently car hire is all the rage in China again these days and the big boys like Hertz and Avis and all them are piling in. Nothing new though – here’s Johnson Car Hire in the late 1920s in Shanghai….

Posted: August 3rd, 2013 | No Comments »

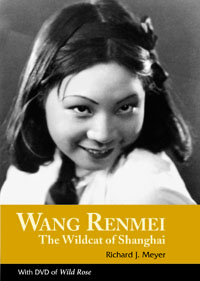

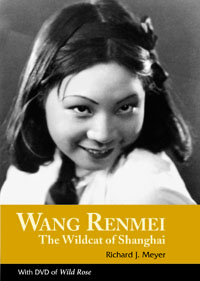

A new book on 1930s screen godess Rang Renmei and an accompanying DVD of Wild Rose from Richard Meyer….

Wang Renmei was on a fast track to become one of China’s leading film stars in the 1930s. Her early films were received with magnificent praise by audiences and critics alike, though she later lamented that she became famous too early and never had a chance to properly study acting. The film Song of the Fishermen in which she sang and played a major role was the first Chinese motion picture to win an International Award in Moscow in 1935.

Wang’s personal struggles reflected the turbulent period from the end of the Qing dynasty to the rise of Deng Xiaoping. This study explores her artistic achievements amid the prevalent anti-feminist and feudal society in China prior to the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949—attitudes which contributed to the downturn of Wang’s promising career and forced her to accept various bit parts among the more than twenty films in which she appeared. In addition, personal problems as well as the Anti-Rightist Movement and the Cultural Revolution led to her hospitalization for mental illness. Wang’s life is emblematic of the experiences of many left-wing and Communist Party members from the Shanghai film community who were viewed with suspicion and enmity by the Yan’an clique headed by Mao and later the Gang of Four. Wang’s performances in World War II for the Nationalist troops as well as her work with the US forces in China had a dire effect on her career after 1949. Yet today, her films are being discovered again.

Richard J. Meyer teaches film at Seattle University. He is the author of Ruan Ling-yu: The Goddess of Shanghai and Jin Yan: The Rudolph Valentino of Shanghai.

“Meyer always writes in an accessible, jargon-free style that invites all interested readers to share his enthusiasm and knowledge for the films he loves so much within their richest historical and cultural context. Thanks to this wonderful book, the Chinese actress Wang Renmei and the film Wild Rose will no longer be obscure within the English-speaking world of film scholarship.â€

— Peter Lehman, director of the Center for Film, Media and Popular Culture, Arizona State University, and co-author of Thinking About Movies: Watching, Questioning, Enjoying

“Wang Renmei is one of the most dynamic and talented film actors in Chinese history, full of tensions and self-contradictions that revealed in part the violence and turmoil of her times and the political complexity of the film industry. This fine book on one of China’s most exciting film artists will appeal to both scholars and general readers interested in early Chinese cinema.â€

—Poshek Fu, professor of history, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign