Posted: March 9th, 2013 | No Comments »

Excellently we have both of my initial Royal Asiatic Society Shanghai–Hong Kong University Press “China Monograph” authors in one place at the same time and while the Shanghai International Literary Festival is on….so, obviously, we put them together to chat…with you….on this great topic…as a special RAS Shanghai event at the SILF 2013.

Tempest in a China Teapot – Friends, Enemies, Fraudsters and Bringing Chinese Poetry to the World

Sunday 10/3/13 – 4pm

M on the Bund, Shanghai

Tickets here

Anne Witchard, University of Westminster (Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie, Lao She in London)

Lindsay Shen, Shanghai Sino-British College (Knowledge is Pleasure: Florence Ayscough in Shanghai)

Moderated by Susie Gordon

One of the culturally significant exchanges that took place in the West’s engagement with China at the beginning of the twentieth century was the race to publish translations and interpretations of Chinese poetry. Ezra Pound emerged from this somewhat controversially as the ‘inventor of Chinese poetry for our time’ – according to TS Eliot. Not so well known are the fierce rivalries, malicious point-scoring and unabashed mud-slinging that he and his contemporaries were embroiled in as they battled for Sino-poetic pre-eminence. Amy Lowell (cruelly dubbed ‘the “hippopoetess†by Witter Bynner and Pound), Shanghailander Florence Ayscough, Lowell, Harriet Monroe and her journal Poetry, Bynner and the infamous Spectra Spoof – there’s a lot more backstabbing, bitchiness and ego involved in translating Chinese poetry than simply words on a page!

Monroe

Authors and academics Anne Witchard and Lindsay Shen discuss the tempest in the China teapot that rumbled on through the interwar years in Chinese poetry studies and read some of the major Chinese works in translation that were at the centre of the storm.

Pound

Speaker Bios:

Anne Witchard teaches modernism and literature at the University of Westminster in London. She is also author of Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie, Â Lao She in London for the RAS Shanghai-Hong Kong University Press China Monographs series and was co-editor of Gothic London; Place, Space and the Gothic Imagination. Anne also runs the conference series and research project, China in Britain: Myths and Realities. She is currently working on a collection of essays on Modernism and Chinoiserie for Edinburgh University Press and a biography of the pioneer of modern dance Margaret Morris.

Lindsay Shen is Associate Professor at Sino-British College, Shanghai. She is Honorary Editor for journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China in Shanghai. She has published in the fields of design and museum studies in Europe and the United States. Â Her latest publication is Knowledge is Pleasure: Florence Ayscough in Shanghai for the RAS Shanghai-Hong Kong University Press China Monographs series.

Susie Gordon is a British writer based in Shanghai. She is the author of Moon Handbooks Beijing & Shanghai guide, and writes for magazines including Shanghai Business Review and China Economic Review. Her poetry collection Peckham Blue was published in London in 2006, and she has contributed to literary journals such as Unshod Quills and HALiterature. She is currently working on a novel set in Shanghai.

Posted: March 8th, 2013 | 1 Comment »

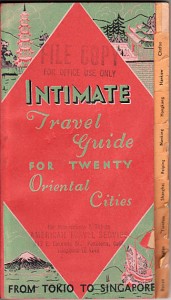

A lovely cover from Stuart Lillico’s 1935 An Intimate Travel Guide for Twenty Oriental Cities from Tokio to Singapore, published by Shanghai’s Mercury Press (linked to the English language evening newspaper of the same name). The Chinese cities included are Canton, Chefoo, Hankow, Hongkong, Nanking, Peiping, Shanghai, Tientsin, Tsingtao and Dairen. Lillico was a prolific book reviewer writing reviews on subjects as diverse as DH Lawrence to Norway in World War Two. He was also, and even more obscurely, the long time editor of Hawaiian Shell News. Just how many subscribers that had remains a mystery…

Posted: March 8th, 2013 | No Comments »

This weekend the Royal Asiatic Society Shanghai and the Beijing International Literary Festival get together….

As regular readers will know last year I published Anne Witchard’s study of Lao She in London, and the modernist influences he received there, as the first book in the new Royal Asiatic Society Shanghai and Hong Kong University Press “China Monographs” series (two a year, and two more to come this year in the summer). This got me thinking that not enough people now read (especially in translation) Lao She’s excellent short stories. Without doubt Ding (1935) is Lao She’s most overtly high modernist short story directly referencing European modernism in its homage to Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). It seemed to me suitable for being converted into a short one-man monologue for an actor to take it to new audiences and also compliment Anne’s book.

And so we have the world premier of Ding, the monologue (please note that’s “monologue”, not “musical” – though Les Mis is doing OK I note!). My first theatrical outing darlings and I’m thrilled (I think you’re supposed to talk like that when you do anything linked to the theatre). As Anne is speaking on Lao She, London and Modernism at the Beijing International Literary Festival at the Beijing Bookworm that seemed a good time to launch the production – so March 9th it is. The good folk at the Bookworm (Alex Pearson and Kadi Hughes) have been wonderfully supportive, and the very talented Fabrizio Massini is directing the piece.

Tickets are now on sale for the debut performance of my adaptation of Ding, at the Bookworm on Saturday March 9th at 22:00 hours (how fringe is that!) For anyone in Beijing during the Festival I do hope you can get along – it’s a great story and hopefully my adaptation will do it at least some justice.The performance will follow on after a discussion about Lao She’s work and time in London with Anne Witchard and Alan Babbington-Smith, also at the Bookworm. Tickets for both events available only at The Bookworm. Box Office hours: 10am-9pm.

“Something’s not quite right about this version of Greece here in our New China… I’m a narrow chested Apollo!!†– Ding

Posted: March 6th, 2013 | No Comments »

Noting Robert Bickers yesterday reminded me that I should also note the brilliant job he’s done around the re-dedication of the gravestone of Sir Robert and Lady Hester Jane Hart. I don’t expect I really need to tell regular readers of this blog the exhaustive history the “IG”, Sir Robert Hart of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service (but if you don’t know or you’re having an off day here’s more on him). Robert, Dr Weipin Tsai at Royal Holloway University of London and others having done a great job restoring the grave (at Bisham in Berkshire) and they recently had a great rededication, of which more details and pictures here. I hope they won’t me reposting an image of the lovingly restored tombstone. There’s more about the day, the classical music that accompanied it and all that here.

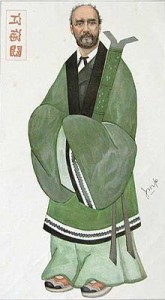

Hart as portrayed in Vanity Fair in 1894

Posted: March 6th, 2013 | No Comments »

It’s impossible to list all the good stuff at the Shanghai International Literary Festival this March (though you can see the whole shebang of a programme here with all ticket details). Here’s a few China-related events that may be of specific interest to readers of this blog…

- Thursday 7th – 12pm – Shelly Bryant (translator of Northern Girls) and Linda Jaivin talk about translation and the issues therein

- Saturday 9th – 2pm – Michael Vatikiotis talks about SE Asian lit

- Sunday 10th – 3pm – James Fallows on Can China Make it?

- Friday 15th – 7pm – Unsavory Elements launch of ex-pat tales with various writers

- Saturday 16th – 3pm – Disappearing Shanghai with Howard French and Qiu Xiaolong

Posted: March 6th, 2013 | No Comments »

The China Lit Fest season is getting underway again – Beijing, Shanghai, Suzhou…and of course the Chengdu Bookworm. Lots going on – click here for full details.

I’d note a few especially interesting things for readers of this blog

8th March – Sichuan women writers Wang Erbei, Zhou Yuxia, Liao Hui, Yan Ge and Liu Guoxin get together on International Women’s Day to discuss women writers in contemporary Chinese society, and how their experience differs across the generations.

9th March – Derek Sandhaus (he of Tales of Old Peking and the reissued Backhouse classic Decadence Mandchoue) will be talking about his new book project on baijiu – warning – some of the “liquid razor blades” may be imbibed at this session

10th March – Jen Lin-Liu, Tom Miller and Derek Sandhaus, three China-based writers whose work and experience covers everything from blogging, journalism and memoir to history and social change, discuss the highs and lows of their writing life and what the future holds for writing on China.

11th March – Tom Miller, author of China’s Urban Billion, speaks on the challenges and potential solutions to China’s rapid urbanisation.

18th March – The Devouring Dragon looks at how an ascending China has rapidly surpassed the U.S. and Europe as the planet’s worst-polluting superpower. Craig Simons argues that China’s most important 21st-century legacy will be determined by how quickly its growth degrades the global environment and whether it can stem the damage.

19th March – Burma time – The Lady and the Peacock is journalist Peter Popham’s biography of “The Lady”, a revealing and illuminating look into celebrated Burmese politician and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s vision and courage as she sought to change her country.

24th March – In The View from the Plateau one of Sichuan’s most prominent writers, A Lai, will discuss his novels, their Tibetan setting, his rise to literary fame and his take on editing the largest-circulation sci-fi magazine in the world.

Posted: March 5th, 2013 | No Comments »

I blogged the other days a short poem called Old China that featured, anonymously, in a 1914 edition of Punch in London. And so my thanks to Robert Bickers of Bristol University (and, of course, numerous works and scholarship on China including the great Empire Made Me and The Scramble for China) for letting me know that the poem was penned by one Patrick Reginald (PR) Chalmers (1872-1942). Mr Chalmers, who was Irish, apparently penned rather a lot of books about shooting, hunting, fishing and deerstalking as well as being a prolific biographer (his subjects included Kenneth Grahame and JM Barrie). He wrote regularly for Punch and The Field, mostly poems also about hunting, fishing and Irish country life. So that’s the author identified, though quite why he decided to stop writing about Ireland, country pursuits and shooting things and pen a ditty about old China with plenty of Chinoiserie motifs is still not really clear. Afraid I don’t have a picture of him but here’s a rather nice old cover of one of his country pursuits tomes…

Posted: March 4th, 2013 | No Comments »

If you happen to be in Hong Kong I’d suggest popping down to the basement of Pacific Place where the Lord Wilson Heritage Trust has a display about its work and about Hong Kong heritage. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, the Trust has created a roving exhibition to be staged at four locations in Hong Kong – it’s at Pacific Place at the moment. The exhibition includes a display of how the early Pokfulam community was formed, why deity boats also take part in the Dragon Boat Water Parade in Tai O, what meanings the ornaments in vernacular architecture carry and what dialects the early indigenous inhabitants spoke, etc. There are also some fascinating objects from the collection of James Wong of everyday ephemera in post-war Hong Kong – books, music, products etc. More details of the exhibit and the Trust here.