Posted: June 1st, 2024 | No Comments »

Reading Truman Capote’s unfinished final novel, the catty Answered Prayers…. a little reference to Shanghai showing how the Bohemian sojounrer culture of the city permeated wider society once…

Posted: May 31st, 2024 | No Comments »

Jonathan Chatwin, whose new book The Southern Tour: Deng Xiaoping and the Fight for China’s Future is the latest publication in my Bloomsbury Asian Arguments series (out now everywhere including Bloomsbury’s site here). Jonathan just wrote an interesting piece for CNN Style on how Zhongnanhai became the secretive centre of Chinese communist power….here…

Posted: May 29th, 2024 | No Comments »

HOW THE US, UK & OTHERS MADE CHINA THE WORLD’S FOREMOST TRADING POWER – Today’s contentious trading relationship between China & the West shows how times have changed, according Made in China by Elizabeth O’Brien Ingleson. I spoke with Ingelson for my May China-Britain Business Council Focus magazine author Q&A – click here to read…

Posted: May 29th, 2024 | No Comments »

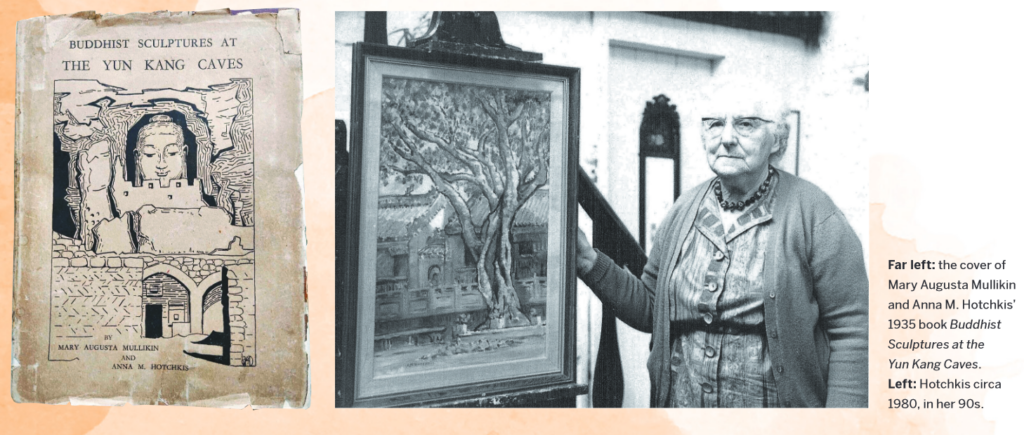

Two intrepid women artists in China, who documented country one painting at a time, almost forgotten today – They have faded from view now, but Anna Hotchkis and Mary Mullikin were intrepid artists who documented China in paintings before World War II tore them apart. Click to read here in the South China Morning Post weekend magazine….

Posted: May 28th, 2024 | No Comments »

An early plug – pre-orders really help books – for Yao Emei’s collection of four short stories, The Unfilial, out this September from Sinoist Books (translators: Honey Watson, Martin Ward, Olivia Milburn, Will Spence). I was lucky enough to get an early copy and it’s among the best writing out of China I’ve read in the last few years.

Posted: May 27th, 2024 | No Comments »

Read the excerpt here. Buy the book here!

Posted: May 26th, 2024 | No Comments »

Selda Antan’s Chinese Workers of the World (Stanford University Press)…

Chinese workers helped build the modern world. They labored on New World plantations, worked in South African mines, and toiled through the construction of the Panama Canal, among many other projects. While most investigations of Chinese workers focus on migrant labor, Chinese Workers of the World explores Chinese labor under colonial regimes within China thorough examination of the Yunnan-Indochina Railway, constructed between 1898–1910. The Yunnan railway—a French investment in imperial China during the age of “railroad colonialism”—connected French-colonized Indochina to Chinese markets with a promise of cross-border trade in tin, silk, tea, and opium. However, this ambitious project resulted in fiasco. Thousands of Chinese workers died during the horrid construction process, and costs exceeded original estimates by 74%.

Drawing on Chinese, French, and British archival accounts of day-to-day worker struggles and labor conflicts along the railway, Selda Altan argues that long before the Chinese Communist Party defined Chinese workers as the vanguard of a revolutionary movement in the 1920s, the modern figure of the Chinese worker was born in the crosscurrents of empire and nation in the late nineteenth century. Yunnan railway workers contested the conditions of their employment with the knowledge of a globalizing capitalist market, fundamentally reshaping Chinese ideas of free labor, national sovereignty, and regional leadership in East and Southeast Asia.

About the author

Selda Altan is Assistant Professor of History at Randolph College.

Posted: May 25th, 2024 | No Comments »

Join us for a fascinating talk with Paul French in conversation with Patrick Winn on his new book Narcotopia: In Search of the Asian Drug Cartel that Survived the CIA on June 8th, 7pm.

The jagged mountains dividing China and Burma belong to the Wa, an indigenous group who have outwitted the CIA to create the world’s mightiest narco-state, controlling more territory than Israel and with more troops than Sweden. Are they crime lords? Or visionaries?

Wa State has become a real nation with its own highways, anthems, schools and flags. Its leaders promise freedom, using profits from trafficking heroin and meth to attain what China’s other frontier peoples, Tibetans and Uyghurs, can only dream of: a state of their own. Patrick Winn embarks on a risky journey of discovery, chasing clues about the forbidden republic from Thailand to Burma to the secretive Wa State itself.

Patrick Winn is an award-winning investigative journalist. He mostly covers rebellion and black markets in Southeast Asia.

Tickets and more details here