San Francisco’s Shanghai Cafe

Posted: March 23rd, 2014 | 1 Comment »Should you have felt a little home sick for Shanghai in 1930s San Francisco, there was always the Shanghai Cafe…..

All things old China - books, anecdotes, stories, podcasts, factoids & ramblings from the author Paul French

Should you have felt a little home sick for Shanghai in 1930s San Francisco, there was always the Shanghai Cafe…..

A charming book of illustrations (though not all the illustrations are charming scenes – if you see what I mean) of James McMullan’s childhood in China. McMullan, born in 1934 in China was left there after his father went to fight in World War II with the Allies. He and his mother moved around a lot – a journey that took them to Shanghai, to Calcutta, to San Francisco and many other cities in-between. McMullan’s book, Leaving China, is a set of short stories, and paintings, that depict moments in that childhood.

It is this dream-like quality of my memories that I wanted to capture in some way in the paintings that accompany the text—to suggest in the images that the events occurred a long time ago in a simpler yet more exotic world, and that the players in that world, including me, are at a distance.â€

It is this dream-like quality of my memories that I wanted to capture in some way in the paintings that accompany the text—to suggest in the images that the events occurred a long time ago in a simpler yet more exotic world, and that the players in that world, including me, are at a distance.â€

Artist James McMullan’s work has appeared in the pages of virtually every American magazine, on the posters for more than seventy Lincoln Center theater productions, and in bestselling picture books. Now, in a unique memoir comprising more than fifty short essays and illustrations, the artist explores how his early childhood in China and wartime journeys with his mother influenced his whole life, especially his painting and illustration.

James McMullan was born in Tsingtao, North China, in 1934, the grandson of missionaries who settled there. As a little boy, Jim took for granted a privileged life of household servants, rickshaw rides, and picnics on the shore—until World War II erupted and life changed drastically. Jim’s father, a British citizen fluent in several Chinese dialects, joined the Allied forces. For the next several years, Jim and his mother moved from one place to another—Shanghai, San Francisco, Vancouver, Darjeeling—first escaping Japanese occupation then trying to find security, with no clear destination except the unpredictable end of the war. For Jim, those ever-changing years took on the quality of a dream, sometimes a nightmare, a feeling that persists in the stunning full-page, full-color paintings that along with their accompanying text tell the story of Leaving China.

Somehow I had never heard of William Marshall’s 1979 novel Shanghai, climaxing in November 1941 (and starting in 1923) and featuring a cast of characters including an SMP cop, a disbarred American lawyer, an old China Hand and many others. It’s actually a pretty rollicking read and a bit of a page turner….

Marshall was an Australian best known for an interesting sounding series of Hong Kong set thrillers called the “Yellowthread Street” – apparently the BBC made a series of the books but I’m afraid I don’t know either the novels or the TV show. Shanghai is a bit of a mystery as it isn’t listed on Marshall’s Wikipedia page (unless it was published under another name in America – the copies below are UK editions).

And, if for nothing else, Shanghai is worth a read as it contains the immortal, and completely true then and now, statement:

“…the one great drawback to a city like Shanghai, with its many advantages, has been that its lack of basic discipline seems to have always attracted men and women of quite the wrong type.”

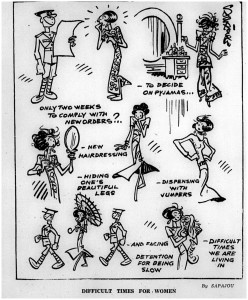

A cartoon from the North-China Daily News from the famous White Russian cartoonist Sapajou in 1934 showing the “problems” women faced in Shanghai following the February introduction of the New Life Movement. Just how little attention Shanghai women paid to the new edicts is of course debatable!

In the Guangdong province in southeastern China lies Dafen, a village that houses thousands of workers who paint Van Goghs, Da Vincis, Warhols, and other Western masterpieces, producing an astonishing five million paintings a year. To write about life and work in Dafen, Winnie Wong infiltrated this world, investigating the claims of conceptual artists who made projects there; working as a dealer; apprenticing as a painter; surveying merchants in Europe, Asia, and America; establishing relationships with local leaders; and organizing a conceptual art show for the Shanghai World Expo. The result is Van Gogh on Demand, a fascinating book about a little-known aspect of the global art world – one that sheds surprising light on our understandings of art, artists, and individual genius. Confronting difficult questions about the definition of art, the ownership of an image, and the meaning of imitation and appropriation, Wong shows how a plethora of artistic practices joins Chinese migrant workers, propaganda makers, and international artists together in a global supply chain of art and creativity. She examines how Berlin-based conceptual artist Christian Jankowski, who collaborated with Dafen’s painters to reimagine the Dafen Art Museum, unwittingly appropriated a photojournalist’s intellectual property. She explores how Zhang Huan, a radical performance artist from Beijing’s East Village, prompted propaganda makers to heroize the female artists of Dafen village. Through these cases, Wong shows how Dafen’s workers force us to reexamine our expectations about the cultural function of creativity and imitation, and the role of Chinese workers in redefining global art. Providing a valuable account of art practices in a period of profound global cultural shifts and an ascendant China, Van Gogh on Demand is a rich and detailed look at the implications of a world that can offer countless copies of everything that has ever been called “art.”

Emperor Henry Puyi on a Japanese postcard, Manchruia (Manchukuo), 1934…I don’t think ChinaRhymers really need the whole Pu Yi, Manchuria, Japanese stooge thing explained again….

Sadly I don’t have a date for this photograph from the London Met Archives but it is the London offices of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company on 21-24 Cockspur Street, near Trafalgar Square offering services to California, Japan, China and round the world. Pacific Mail was an American steamship line that started operations in 1848 transporting mail and passengers. Their trans-Pacific services were started in 1867 connecting San Francisco to Yokohama, Hong Kong and Shanghai. It was a popular line, due to lower costs, with Japanese and Chinese immigrants to the USA.